MANTRAYA ANALYSIS#22: 20 FEBRUARY 2018

SHANTHIE MARIET D’SOUZA

Abstract

The sudden surge in violence and gory blood bath in January 2018 brought about renewed international media attention to Afghanistan. The growing number of attacks indicates a deteriorating security situation, deepening political crisis and power contestations. In the ensuing battle of area domination between the Islamic State and the Taliban, more blood is being spilled in the streets of Kabul. Moreover, both the Taliban and the Islamic State also appear to be benefiting from the larger geopolitical rivalry of great powers. As the date of presidential elections draw near, power reconfigurations and realignments can lead to an increase the levels of violence. In the light of these developments, it is critical to shore up Afghan government capacities and step up efforts at institution building in key sectors to prevent the backsliding of Afghanistan into further instability and chaos.

(Scene in the aftermath of an explosion of a bomb hidden inside an ambulance,

which killed over 100 people in Kabul on 27 January 2018, Photo Courtesy: NewsOne TV)

The gory blood bath witnessed in Afghanistan in January 2018 is shocking, saddening, and yet not so surprising. Resilience among local Afghans is hardly a matter of choice, while the elite remain well protected behind the blast walls. The place I had moved about relatively freely a decade back is now known as “Fortress Kabul”. Every visit since then to the country and particularly to government offices and diplomatic missions, I have seen a steady increase in the number of security barricades and height of the blast walls. The most emblematic of this is the American embassy in Kabul.

The recent attack on January 20 on the Intercontinental Hotel, venue for a conference of provincial telecom officials, is worrisome. In September 2016, I was at the Intercontinental for a workshop organised by an Afghan ministry on local governance. The layered security arrangements made visits to such high-security hotels cumbersome. Despite those security measures, I had been repeatedly warned to stay clear of such high-profile venues. Rumors are rife in Kabul about the insider-outsider collusion with paid information leaks to the insurgents. Most of these attacks are construed to be a handiwork of such collusion. This has further fueled distrust and widened the gap between people and the government. The insurgents are using this space not only to further discredit the government but to spread a pervasive sense of fear and deepen the ethnic faultlines. In light of the forthcoming presidential elections in 2019, this distrust and fear could have a telling effect.

Surge in Violence: Battle of Narratives

Sudden spike in violence in January 2018, the first month of the year, brought about renewed international media attention. The growing number of attacks indicates a deteriorating security situation. Kabul has attempted to avoid such negative publicity, by, among other things, underreporting of casualties. This is mostly to win the ‘battle of narratives’ and avoid the concomitant negative fallout of international media reporting which impacts on the national morale as well as international support. The scaling down of international aid by donors, who are weary of funding a country that cannot demonstrate success and is caught in an unending state of violence for perpetuity, remains a cause of worry for Kabul.

Taliban and Islamic State Contestation

In the ensuing battle of area domination and contestation between the Islamic State and the Taliban, more blood is being spilled in the streets of Kabul. In May 2017, a lorry bomb tore through Kabul’s diplomatic quarter and killed more than 150 people. Fresh security measures were implemented. And yet, terrorists continue to strike, almost daily and at will. On 20 January 2018, Taliban gunmen evaded security guards at the front of Kabul’s Intercontinental Hotel, entering via a kitchen door before killing more than 40 people in a 14-hour rampage. On 27 and 28 January, two more attacks- one by the Taliban and the other by the Islamic State, underlined intelligence failures and holes in the city’s security set up. On 28 January, the Islamic State’s Inghimasi cadres struck the Marshal Fahim National Defense University having scaled a wall at dawn before bursting into the barracks and firing wildly. At least 11 cadets were killed and 15 wounded before the attackers were shot dead.[1]That attack had followed a Taliban bomb hidden in an ambulance that killed 103 people in the heart of the capital on 27 January.[2]

(Source: Hugh Tomlinson and Haroon Janjua, ‘Isis and the Taliban

compete to spread carnage in Kabul’, The Times, 30 January 2018.)

The Reinvigorated Taliban Insurgency

The Taliban insurgency is no longer a pre-2001 monolithic organization. It is a decentralized rural insurgency with undiminished ability to target urban centres. Notwithstanding reports of weakening of the insurgency due to infighting, leadership struggles, and differences over reconciliation with the Afghan government, the Taliban is said to be in control or contests 40 to 50 percent of Afghanistan’s nearly 400 districts, which is more territory than at any time since U.S. forces entered the country in 2001.[3] Their campaign of indiscriminate violence and killings has led to an exponential increase in fatality rates among Afghan security forces and civilian casualties. Inadequate state response has meant that the insurgents have been able to step up their destabilising activities with impunity from their sanctuaries across the southern border.[4]

Growing Daesh challenge

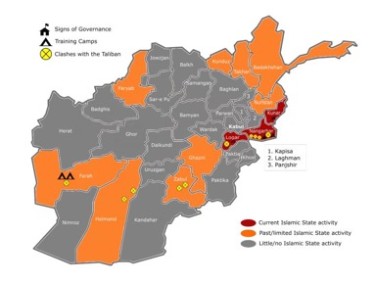

The Islamic State (IS, also known as Daesh), whose presence and strength have been alternately confirmed and disputed, continues to survive the pounding of airstrikes by the United States, including the ‘mother of all bombs’. The actual impact of such strikes remains contested and analysts tend to be guided by the official claims. One such claim is that the IS has apparently been driven out of several districts in its eastern stronghold of Nangarhar province. However, attacks in Nangarhar have continued. On 24 January 2018, for instance, the IS underlined its continued presence in the province by carrying out an attack on the office of Save the Children organization. The IS now has refocused on capital Kabul by operating through new found cells and recruitment of cadres. In the first week of February 2018, in Kabul’s western Qala-e-Wahid district, security forces discovered an IS hideout filled with explosives and suicide vests.

Additionally, the IS has reportedly gained in strength in northern Afghanistan, between Sar-e-Pul province and eastern Badakhshan province. The IS has long sought a foothold in the north, vying for links into the republics of Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan, from which it drew much of its fighting strength in Syria and Iraq. That now appears to have turned into a possibility. Its cadre strength in Afghanistan is officially estimated to be 5000 fighters, which include former members of the Tehrik-e Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), fighters from outside the immediate region, as well as Afghan Taliban defectors. In the provinces of Jowzjan, Faryab, and Kunduz, the IS cadres, backed by foreign fighters are challenging the Taliban and are building trafficking routes into neighbouring Central Asian states.[5] However, despite its expansionist and disruptive potential, the IS, which started its activities in 2014 in Afghanistan, is not quite near the strength and the power of the Taliban.

(Source: Activities of the Islamic State summarized by the Middle East Institute)

Sponsors, Proxy Warfare and Great Power Competition

In the battle for area domination and contestation, both the Taliban and the IS also appear to be benefiting from the larger geopolitical rivalry of great powers. Accusations and counter-accusations are rife. Russia has expressed concerns on with the rise of IS activity in northern Afghanistan, which could be used as a launch pad to fuel Islamist insurgencies inside its territory. The Afghan and US governments, on the other hand, have accused Kremlin of opening channels of communication and funnelling weapons to the Taliban. Afghan government officials have alleged that small arms and RPGs from Russia are being provided to the Taliban. Likewise, reports from the field indicate that Iran, Pakistan and China are continuing their support to the Taliban through direct or indirect means.

Political Infighting and Power Contestations

The deteriorating security situation is further compounded by the protracted political feuds and divisions within the National Unity Government (NUG). The powerful first Vice President General Abdul Rashid Dostum has been prevented from returning to Afghanistan from Turkey by the government. In December 2017, President Ghani dismissed important Tajik powerbroker Atta Mohammed Noor as governor of northern Balkh province[6]. Atta, one of the leaders of the Jamiat-i-Islami political party, which holds half the seats in the coalition government, has refused to step down. The party has condemned Ghani’s decision as “rushed, irresponsible, and against stability and security of Afghanistan.” Noor’s defiance has been sought to be replicated by another Jamiat-i-Islami leader and provincial governor of Samangan, Abdul Karim Kadam, who too has refused to step down after being dismissed by the President. Ghani had sacked four provincial governors in February 2018.

As the date of elections draw near, power reconfigurations and contestations can aid escalation in violence levels. The present NUG is an experiment which is yet to ratified by the Constitutional Loya Jirga (CLG). The parliamentary elections due five years back have not been held yet. The deteriorating security situation is going to make the conduct of elections difficult which will in turn feed into the insurgent propaganda of the present government being a “puppet regime”.

‘New’ American Strategy

Surge in violence in Afghanistan has followed the announcement of a new strategy for Afghanistan and Asia by US President Donald Trump in August 2017. US officials had claimed that the Taliban were being forced back to the negotiating table by President Trump’s strategy of reliance on kinetic operations. The Pentagon looks ready to deploy a further 1,000 US troops to Afghanistan in the spring, bringing the American task force to 15,000. In the absence of concrete actionable strategy, Trump’s attempt to make Pakistan amend its destablising policies in Afghanistan has coincided with the rise in the number of high profile attacks in Kabul. This could very well be Pakistan’s last-ditch effort to remain relevant in any US strategy towards the war-torn country.

As the Afghan forces battle to stem the surge in attacks in Kabul, the Taliban have vowed to continue their violence. “The Islamic emirate has a clear message for Trump and his hand-kissers,” Zabihullah Mujahid, a Taliban spokesman said. “If you go ahead with a policy of aggression and speak from the barrel of a gun, don’t expect Afghans to grow flowers in response”, he added.[7] The latest in the series of its innuendoes, the Taliban on 14 February 2018 issued a 3000-word letter urging “the American people, officials of independent non-governmental organizations and the peace-loving Congressmen” to press their government to withdraw from Afghanistan. The letter reminded them that the Afghan war is the longest conflict in which they have been embroiled — and at a cost of “trillions of dollars.” It repeated the Taliban’s longstanding offer of direct talks with Washington, which the United States has repeatedly refused, saying peace negotiations should be between the Taliban and the Afghan government. The letter promised a more inclusive regime, education and rights for all, including women. However, it seemed to rule out power-sharing, saying they had the right to form a government.[8]

Afghan COIN Strategy

The inability of the Afghan forces to quell the complex insurgency can be attributed to a lack of indigenous counter-insurgency (COIN) strategy. Until 2015, there had been little effort to develop an indigenous Afghan COIN strategy, away from the external advice-based model. But a sense of urgency has emerged after a string of Taliban victories.[9] During 2017, a more coherent approach prioritising internal reform (anti-corruption), defence of cities and highways, tactical offensive operations by special forces, and reliance on militias to challenge Taliban control over rural areas is being formulated, even though this is still marked by lack of widespread consensus.

India’s Policy

India preferred mode of ‘wait and watch’ policy in Afghanistan will limit its potential for consolidating its gains. In India’s strategic circles, debates over putting boots on Afghan ground or to expand its development assistance programmes continue with little understanding of the changing dynamics on the ground. However, given Afghanistan’s strategic importance, a policy that accords secondary importance to a primary interest would not suffice. It is gradually becoming clear that the policy makers need not wait for the conditions to deteriorate further to intensify India’s assistance. New Delhi has tremendous advantages and goodwill in Afghanistan. It should capitalize on that. Following the benefits of the Salma dam project, there are requests from other provinces for similar projects.

While the US and India might have announced the strategic partnership to work together in Afghanistan, it will be useful to know the components of such a policy and how will those policy objectives be achieved. In the short term, beyond naming and shaming Pakistan, President Trump has to demonstrate what action his administration will take to stop the continued support for the insurgency. More [i]importantly, India and US will need to chart a course of action for institution building in key sectors- security, political and governance sectors for the long-term stabilization of Afghanistan.

India needs an ears-on-the-ground policy. At the time of shifting dynamics, New Delhi seems to be disconnected with the undercurrents which could change the present situation in Afghanistan. Any further destabilization in Afghanistan will not be without serious consequences for India and the international community.

References

[1] Thomas Joscelyn, “Islamic State branch claims attack on Afghan military academy”, Long War Journal, 29 January 2018, https://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2018/01/islamic-state-branch-claims-attack-on-afghan-military-academy.php

[2] “Kabul attack: Taliban kill 95 with ambulance bomb in Afghan capital”, BBC, 28 January 2018, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-42843897.

[3] According to recent estimates the Taliban currently controls 41 districts and contests an additional 118. The assessment is developed by regularly evaluating local, open-source reports for each district in Afghanistan. A controlled district is one in which the Taliban is openly administering a district, providing services and security, running the local courts and imposing sharia law. Bill Roggio & Alexandra Gutowski, LWJ Map Assessment: Taliban controls or contests 45% of Afghan districts, FDDs Long War Journal, 26 September 2017, https://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2017/09/lwj-map-assessment-taliban-controls-or-contests-45-of-afghan-districts.php

[4] Bill Roggio & Alexandra Gutowski, Mapping terrorist groups openly operating inside Pakistan, FDDs Long War Journal, 23 August 2017, https://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2017/08/mapping-terrorist-groups-openly-operating-inside-pakistan.php

[5] Letter dated 17 January 2018 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolutions 1267 (1999), 1989 (2011), and 2253 (2015) concerning Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals, groups, undertakings and entities addressed to the President of the Security Council.

[6]Mujib Mashal, Afghan Governor Refuses to Leave His Post, Escalating Showdown, The New York Times, 23 December 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/23/world/asia/afghanistan-atta-muhammad-noor.html?mtrref=www.google.com&gwh=DAE5AFEDCD8BBAB43FF9060A6744531F&gwt=pay

[7] Hugh Tomlinson and Haroon Janjua, Isis and the Taliban compete to spread carnage in Kabul, The Times, 30 January 2018, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/isis-and-the-taliban-compete-to-spread-carnage-in-kabul-ldrrnwhrf

[8] Taliban letter addresses ‘American people,’ urges talks, The Associated Press, KABUL, 14 February 2018, http://abcnews.go.com/International/wireStory/taliban-letter-addresses-american-people-urges-talks-53083303

[9] Antonio Guistozzi, Counterinsurgency Challenge in Post-2001 Afghanistan in Shanthie Mariet D’Souza (ed.), Special Issue on “Countering insurgencies and violent extremism in South Asia”, Small Wars & Insurgencies (UK: Routledge), vol.28, no. 1, February 2017.

(Dr. Shanthie Mariet D’Souza is the founder and president of MISS. This Analysis is published under Mantraya’s ongoing ‘Mapping terror & Insurgent Networks’ and “Islamic State in South Asia’ projects. All Mantraya publications are peer-reviewed.)