MANTRAYA SPECIAL REPORT#04: 11 MARCH 2016

JHINUK CHOWDHURY

Abstract

Three key focus areas of China’s massive infrastructure build up along the Sino-Indian border are: integrating the border region to Chinese mainland, accessibility to the Line of Actual Control (LAC), and strengthening counter offensive capabilities. This calls for an urgent attention from New Delhi as a reactionary policy would not suffice.

Introduction

Some positive developments in past years notwithstanding, Sino-Indian bilateral relations continue to be marred by the war both countries fought 54 years ago. The Line of Actual Control (LAC) that divides both is not recognized by China. Many Indian thinkers acknowledge the LAC is drawn with an ink of perception. India’s perception of what constitutes part of its territory is vastly different from that of the Chinese. An extension of its unambiguous claim over the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh, Beijing in the past years has stepped up its border infrastructure projects. This enables the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to retain a clear advantage in military mobilization and capabilities vis-a-vis their Indian counterparts. Indian response, on the contrary, has been reactionary.

Beijing’s steadily growing infrastructure build up along LAC include roads, railway line, and fibre optics following a three pronged strategy.

Beijing’s steadily growing infrastructure build up along LAC include roads, railway line, and fibre optics following a three pronged strategy. Firstly, it aims at integrating its front lying region with Chinese mainland – a strategy most visible in China’s infrastructure projects in Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR), which it occupied in 1949. A defense buildup for quick mobilization supported by a strong air defense system and an uncomplicated administrative framework, is the second objective of this strategy. And thirdly, the strategy is all about extending China’s accessibility to the LAC through rail networks, and in many cases using some of the bordering countries like Nepal and Pakistan to strengthen its strategic hold in the border areas.

Highways to ‘Sinocize’ Tibet

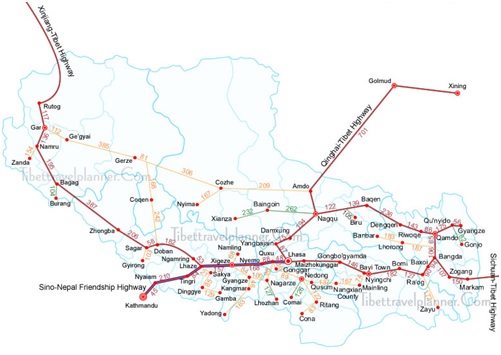

Entire TAR is connected to China’s mainland and interiors by ‘all weather’ road networks. Key TAR highway networks of China are:

- The Eastern Highway that connects Chengdu in Sichuan Province and Linzhi (Ngiti) in the TAR up to Lhasa. The highway, originally called the Kangding-Tibet Highway, is a high-elevation road starting from Chengdu, capital of Sichuan province, on the east and ending at Lahsa, capital of TAR, on the west. With a South Line length of 2,115 kilometres and North Line length of 2,414 kilometres, building of Eastern Highway started in April 1950, and was opened for traffic on 25 December 1954.

- The Central Highway connects Xining in Qinghai Province to Lhasa. Also called the Qinghai-Tibet Highway, this road network was opened along with the Eastern Highway in 1954. It was asphalted in 1985 and is said to be the world’s longest asphalt road. More than 80 percent of freight transport go via this highway. Three major overhauls of the highway has cost nearly three billion yuan ($362 million).

- The Western Highway connects Xinjiang Province to the TAR, by linking Kashgar and Lhasa. After a diversion to Khunjerab Pass it subsequently becomes the Karakoram Highway and touches Gilgit in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoK). It is 3,105 kilometres long.

- The 716 kilometres-long Yunnan-Tibet Highway connects the provinces of Yunnan and the TAR. It branches off from the Eastern Highway and then connects to Yunnan and the TAR.

(Figure 1: Road Map of Tibet, Source: Tibet Travel Planner)

In November 2013, China opened an all weather road linking Medog County in the TAR, which is also close to the Indian border in Arunachal Pradesh (referred as ‘South Tibet’ by China), to the rest of China. With this, every TAR county is connected to a highway network in China. In July 2013, the Chinese government announced that it will spend about 200 billion Yuan or $32.3 billion to build a road network centred around Lhasa and extend the combined length of the TAR’s highways to over 110,000 kilometres.

Expanding its communication network is yet another important feature of integrating the border region with the Chinese mainland. As many as 665 townships of the TAR have been connected with Optic Fibre Cable (OFC). This project effectively covers 97.5 percent of all townships in the TAR. About 3231 villages (61.4 percent of all villages) have access to broadband internet.

Support system for border forces

As per a 2015 estimate, China has positioned about 300,000 People’s Liberation Army (PLA) troops and six Rapid Reaction Forces or RPF at Chengdu in the TAR. The focus seems to be on creating a reliable and robust support system for this front line force. For instance all Military Supply Depots are connected to Lhasa by radio and OFC establishing real-time connectivity. China has a single unified Commander responsible for the armed forces in the TAR and along Indian border.

Plans are underway to construct newer airfields and upgrading advanced landing grounds (ALGs) and helipads which will strengthen People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) fighter aircrafts’ striking range.

The most important line of support for the border forces, however, is the air mobility and helicopter-borne military operations. China already has five operational airfields in the TAR region- at Gongar, Pangta, Linchi, Hoping, and Gar Gunsa. Plans are underway to construct newer airfields and upgrading advanced landing grounds (ALGs) and helipads which will strengthen People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) fighter aircrafts’ striking range. The PLAAF operations has apparently intensified since 2012 when it carried out weapon firing trials at high altitude ranges in the TAR for the first time. Currently, two regiments of 24 aircraft, J-10s and J-11s, operate virtually on a permanent basis from the TAR airfields. Their operational philosophy in TAR is said to be focusing on strong air defence to create local air dominance, and support to ground forces primarily for integrated airborne assault operations.

Karakoram Highway

The Karakoram Highway (KKH) that connects Abbottabad in Punjab (Pakistan) to Kashgar in Xinjiang region of China has generated much concerns in New Delhi. The Karakoram ranges also form the de facto border along the LAC. It consists of the Ladakh region in India, Gilgit-Baltistan region in Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (PoK) and touches the Aksai Chin region occupied by China. The construction of Karakoram Highway, China’s only overland link to Pakistan, began in 1967. Initially built jointly by Pakistan and China, it is maintained by China. There are proposals to transform KKH into an economic corridor, also referred to as the Karakoram Corridor (KC), by making it into an all-weather expressway. Five 7 seven kilometre-long tunnels have been constructed to ensure year-round land connectivity. In September 2015, the Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif inaugurated the tunnels, also called Also called the Pakistan-China Friendship Tunnels. Fears have been expressed in New Delhi that these tunnels could be used not only for rapid movement of troops and material from China and Pakistan or for stationing missiles in PoK. During the Soviet War in Afghanistan the highway was used to equip the Taliban. Pakistan had also used this road network to ship American weapon systems to China for reverse engineering. China can indeed use the KKH network to watch over Indian activities in the region through listening posts and advanced surveillance bases in PoK. The air fields in PoK might be used against India by the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) to its benefit.

Fears have been expressed in New Delhi that these tunnels could be used not only for rapid movement of troops and material from China and Pakistan or for stationing missiles in PoK.

With the unveiling of the $46 billion China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) in April 2015, the KKH has assumed a new strategic dimension. The corridor will extend the KKH till Pakistan’s port city of Gwadar in Balochistan. Once the Gwadar port is connected to the KKH through the CPEC, it will help transport of goods docked at Gwadar port directly to China. Analysts suggest the corridor will help China evade any threat from Indian or US naval presence in the Indian Ocean.

Trains to LAC

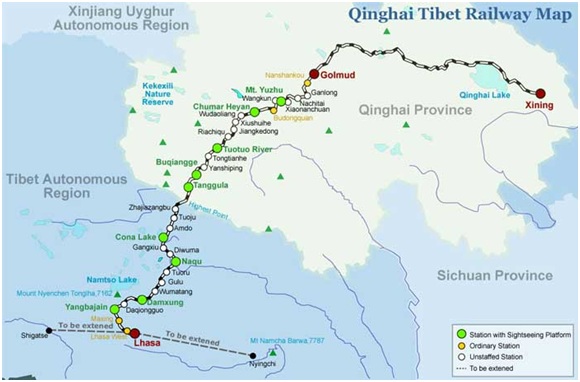

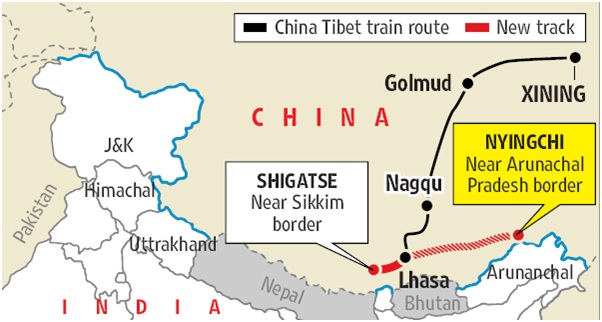

Railway networks seem to be the next line of strategy for China to enhance accessibility to the LAC. Networks like the well known Qinghai-Tibet Railway connecting to Lhasa, is said to be focusing on mobility of troops in the LAC.

(Figure 2: Qinghai Tibet Railway Map, Source: Tibet Discovery)

The Lhasa–Shigatse or Lari Railway line, which was completed in July 2014, connects Lhasa to the city of Shigatse or Xigaze, which borders India’s Sikkim, apart from Nepal and Bhutan. Similarly, China has also startedconstruction of the Lhasa-Nyingchi railway line in 2012. Nyingchi is a prefecture-level city in southeast of the TAR. As per reports, the Lhasa to Nyingchi line, with a declared investment of 33 billion yuan ($5.4 billion), involves building of 402 kilometres new lines with a designed speed of 160 kilometre per hour.

(Figure 3: China-Tibet train route, Source: Tibetan Review)

Efforts are also on to complete construction of the Lhasa-Yatung railway line by 2020. Yatung sits at the entry point of Chumbi Valley in Tibet and is connected to the Indian state of Sikkim via the Nathula Pass. Similarly, work on the Lhasa-Linzhi railway line is also work in progress. Linzhi is located at about 70-80 kilometres from the Indian border. Of particular interest is the 770-kilometre Lhasa-Khasa railway line which China began constructing in 2008. Located near Nepal border this line extends from Kashgar in the Xinjiang Province to Aksai Chin.

With China’s increasing profile in Nepal, the Lhasa-Khasa railway line could strategically strengthen Beijing’s hold on Aksai Chin, the territory claimed by India as its own. The rail link is likely to be aligned with the Friendship Highway from Shigatse or Xigaze to Khasa, and further till Kathmandu.

Even though border infrastructure has received precedence under the Modi government, even to catch up with China appears to be a task fraught with glorious uncertainties.

Conclusion

Contrary to this, report of the Indian Parliament’s Standing Committee on Defence, released in 2013-2014 terms the Indian infrastructure along the Sino-Indian border to be in a dismal state. Of the 73 all-weather roads, along the Sino-Indian border that India had identified for construction in 2006, just 18 have been completed. Of the 27 roads that were to be constructed by the Indo-Tibetan Border Police (ITBP) forces deployed along India’s border with Tibet – just one is complete with “as many as eleven roads behind schedule” and even their detailed project reports not yet finalized. The plans to construct 14 strategic railway lines near the border have registered “nil achievement.” Even though border infrastructure has received precedence under the Modi government, even the task of catching up with China appears to be mired in glorious uncertainties.

(Jhinuk Chowdhury is a project intern with MISS. This Special Report is a part of Mantraya’s Borderlands; and China and South Asia projects. All Mantraya publications are peer-reviewed.)