MANTRAYA ANALYSIS#03: 02 JULY 2015

SURYA VALLIAPPAN KRISHNA

Abstract

The argument that South Asia in general and India in particular would maintain its insularity from the Islamic State’s influence is delusional. The threat for India is real and could be far more lethal than familiar Islamist groups. With the IS already showing signs of presence in parts of South Asia, it could be only a matter of time before it announces its arrival in India in a grand fashion.

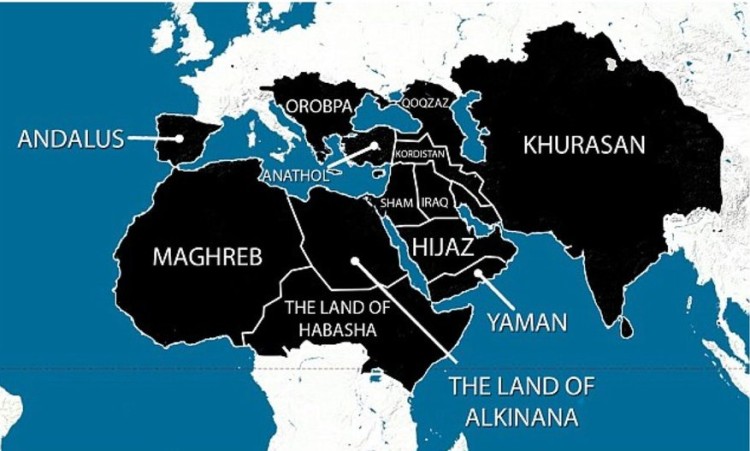

A year since its declaration of intent, the Islamic State (IS) has captured the world’s imagination like no other terrorist organisation. It continues to demonstrate supernormal growth and area dominating abilities. In this context the argument that South Asia in general and India in particular would maintain its insularity from the outfit’s influence is delusional. The first propaganda video featuring Caliph Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi in late June 2014 after the declaration of the Caliphate showed him make explicit and specific references to Indian Muslims and to those of its neighbours to rise up, wage Jihad and establish the Islamic State of Khurasan. Khurasan is the proposed geographical entity covering almost the entire South Asian region. India figures prominently in the outfit’s future plans.

Source- www.geocurrents.info

Having the second largest Muslim population (180 million according to the 2011 census constituting 14.2 percent of the country’s population) with a large majority of them being so-called young vulnerable Muslims, a Hindu nationalist Government in New Delhi with an allegedly questionable record related to treatment of the Muslim community and a ready-to-exploit sectarian divide between the Shia and Sunni groups (Shias are roughly estimated to be 22 to 28 percent of the Indian Muslim population), India arguably is a prime ground for the IS. And yet, the case is often made out that the IS, its affiliates and fan-boys will never succeed in India.

On 19 March 2015, Home Minister Rajnath Singh made a statement regarding how the IS has failed in the Indian context. Singh said,

“I am happy to note that the influence of Islamic State on the Indian youth is negligible. The failure of IS to attract Indian Muslims, who constitute the second largest Muslim population in the world, is due to their complete integration into the national mainstream. Indian Muslims are patriots and are not swayed by fundamentalist ideologies. Extremism is alien to their nature”.

The official line thus far has been to parrot the strength of India’s unity in diversity, integration of all religious communities in the national mainstream, and the supremacy of the Indian identity. This has also been attributed to the fact that pluralism has had a long history in India. Although much of this is true and for long Indian Muslims have refused to be a part of Global Jihad, to expect the past to be able to prevent a slide into chaos in future could be strategically myopic.

The Indian Government has underplayed the IS threat. India has also been treading carefully with relation to its foreign policy agenda in Iraq and Syria, opting out of the United States-led coalition potentially thwarted dissatisfaction among members of the Indian Muslim community. While the past year has witnessed a march of some Indians to join the IS in Iraq and Syria, there isn’t an agreement on the exact number of such people who have been associated with the violent agenda of the outfit. Reported cases of radicalisation in the media differ from the ones that politicians and security officials confirm, In November 2014, National Security Advisor (NSA) Ajit Doval said that there could not be more than 10 cases of which five or six persons were those with the intention of joining the Islamic State. Doval’s statement contradicted his predecessor M K Narayanan’s account in September 2014 that Indians numbering between 100 and 150 – mostly engineers – have left the country to fight with the IS. In either case the number of Indians with the IS has been extremely small compared to the overall Muslim population. Given that India’s attempts at establishing either a comprehensive counter-extremism programme or a explicit counter-narrative that addresses violent extremism are incomplete projects, the weak Indian association with the IS is puzzling and could be a erroneous source of satisfaction.

Interestingly, many IS foreign fighters from Westerns and European countries have been second or third generation Muslims of South Asian descent, some like Abu Rumaysah being of Indian origin, Abdul Raqib Amin being of Bangladeshi origin. Racism, discriminatory experiences in association with a strong identity crisis is seen to be the underlying cause for radicalisation.

This is where the role of the media has been overlooked, the influence the media has had is enormous. The Indian media in recent times has been at the forefront of controversy. Whether being accused of fronting for corporate bigwigs or dishing out content that lacks objectivity, only on rare occasions that select India media has received accolades for its sensitive coverage of issues of terrorism. Indian media’s coverage since the Mumbai attacks, with fantastic visuals and poor content, has been an oft-cited case of failure in cooperating with counter terrorism operations.

The IS poses a new threat; the group with its ruthless brutality makes Al Qaeda look moderate while its cutting edge video production skills gives it a all pervasive capacity to induce fear. In contrast, the Indian television and print media’s attention on IS-related content has been sporadic as compared to the European media portraying it as an existential threat. Unlike its peers in the developed world, the Indian media reported events ‘as they occurred’- basis and its coverage was not characterized by an underlying narrative that focussed on the IS content regularly. This has strongly contributed to a culture which views the IS as a distant threat without much of immediate domestic repercussions. Recent examples of this trend is the hyperbole and little else in covering three stories: One was related to the massive efforts to rescue Indian workers from IS stronghold in Iraq undertaken by the Ministry of External Affairs, while the second was related to radicalisation of Areeb Majeed, the young man from Kalyan who travelled to the IS stronghold and returned. The third was in connection to the arrest of Mehdi Biswas, an Islamic State sympathizer with an influential twitter handle (@ShamiWitness).

The Islamic State is showing signs of expanding. The militant culture in Pakistan and Afghanistan seem to be particularly receptive to this new breed of political violence. Some of the Pakistani Taliban commanders and Jundullah, a splinter of the Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) have pledged allegiance to the self proclaimed Caliphate. In November 2014, the provincial government of Balochistan told Islamabad in a confidential report that IS has claimed to have recruited a massive 10 to 12,000 followers from the Hangu and Kurram Agency tribal areas. In addition, Indian groups such as the Indian Mujahedeen (IM) could wreak havoc with support of the IS transnational network. In September 2014, the National Investigative Agency in a case relating to the IM told the Delhi High Court that the group wanted to create an Iraq-Syria situation in India with the intention of forming an Islamic State in the region. The volatile Kashmir region, where this Islamic State flag has been cited on a number of occasions could play out to be a theatre of violent conflict for the IS Islamic State with Indo-Pak diplomacy and talks reaching an inevitable deadlock. The inclination of Pakistan in attempting to use the IS as an anti-India instrument cannot be ruled out.

The South Asian dream of the IS is yet to take full shape. The threat for India, however, is real and could be far more lethal than familiar Islamist groups such as the Lashkar-e-Toiba. With the IS already showing signs of presence in parts of South Asia, it could be only a matter of time before it announces its arrival in India in a grand fashion.

(Surya Valliappan Krishna is a postgraduate student at the Department of War Studies, King’s College, London. This brief has been published under Mantraya’s “Islamic State in South Asia” project. Surya is a lead researcher with the project.)