MANTRAYA ANALYSIS#42: 04 FEBRUARY 2020

MRIDUL UPADHYAY

Abstract

In the context of peace-building in India, youth are either considered as victims or perpetrators of violence, but rarely as enablers who can play an important role in peace-building. This situation is prevalent despite youth having been granted a legally binding United Nations Security Council Resolution 2250 that highlights such role. Amidst such prevailing narratives and misconceptions, young people are subjected to policy negligence, hard-fisted security measures, and experiences of exclusion from multiple stakeholders. This needs to change if the youth need to play a constructive role in peace building in India. This article examines the policy for the youth in India and suggests ways of actively engaging the youth in peace-building and prevention of violent extremism.

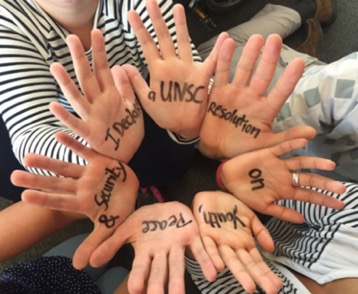

(Image Courtesy: UNOAC)

The Global Context : Youth and Peace

After years of advocacy by young people and youth-focused organisations, the United Nations Security Council Resolution 2250 was passed on 9 December 2015, which is first of a kind to address youth, peace and security (YPS) elements.[1] It brought to light the importance and positive role youth play in peacebuilding and prevention of violent extremism (PVE), enumerating five key pillars – participation, prevention, protection, partnership, and disengagement and reintegration. The resolution calls on various actors, including member states, to engage youth as partners and leaders, increase the meaningful participation of youth in decision making, as well as to prevent and resolve conflict and prevent violent extremism. It is important to underscore that the title of resolution 2250 is “Maintenance of International Peace and Security” which is a reference to Chapter 7, Article 39 in the UN Charter. And Security Council Resolutions under Chapter 7 are binding on all member states, including India.[2]

As per Global Peace Index (GPI) 2019, released by the Australian think tank Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP), India stands at 141st position, among 163 countries, and at fifth in the South Asian region. The GPI takes into account parameters like number of deaths due to internal disturbances, level of perceived criminality in society, level of respect for human rights, terrorist activities, number of imprisoned persons, numbers of violent demonstrations, and access to small arms and so on. Such ranking places India as one of the most violent countries in the world. Other than communal riots[3], there are active separatist movements, tribal unrest, gender-based violence, caste-based injustice and wealth disparity which adds to the sense of injustice, alienation, and a persisting climate of violence.

‘Youth Bulge’ in India

India is also one of the youngest nations in the world, with about 65 percent of the population under 35 years of age. The youth in the age group of 15-29 years (as per National Youth Policy 2014) comprise 27.5 percent of the population, which makes about 380 million youth in India.[4] The National Youth Policy of India, launched on 9 January 2014, is the most updated 94-pager policy document.[5] In this policy, the words like ‘education’, ‘skills’ and ’employment’ have been referred for 105 times, 71 and 45 times respectively. ‘Harmony’ is referred for just eight times. Most curiously, the word ‘peace’ gets no mention in the entire document.

So even when young people are among the most affected by multiple and often interlinked forms of violence that plague the country and communities, bearing enormous and long-lasting human, social and economic costs[6], India neither seems to accept this context and its adverse effect on youth, nor address the violence from perspective of conditions on the ground for the youth. There is no second opinion on the fact that young men aged 15 to 29 account for the majority of casualties of lethal armed violence[7]; while young women (as well as young men) face risk of physical and sexual abuse and exploitation.

Policy Myopia

The cycle of poverty, hopelessness and frustration amongst youth in India gets fueled by lack of access to education, basic social services, economic opportunities, grievance over injustices, and a generalized distrust in political system. Even then, participation of youth in in violence and extremism has remained extremely limited.

Global research too demonstrates that youth who participate actively in violence are a minority, while majority of youth, despite the injustices, deprivations and abuse they confront daily, particularly in conflict contexts, do not participate in violence. On the contrary, many play active and valuable roles as agents of positive and constructive change.[8] Youth-led social and political movements, peacebuilding and conflict-prevention interventions, taking place at the local and national level, help build more peaceful societies and catalyze more democratic and inclusive governance.[9]

The policy negligence in India towards the youth could primarily be due to the fact that ‘protection, promotion and partnership’ depend a lot on what one stakeholder thinks about another one; useless/useful, threat/ally, responsibility/burden, right-holder/demographic-number. Due to the prevailing narratives of youth as victim/perpetrator/demographic-advantage, young people go through experiences of exclusion from multiple stakeholders in India. On the other hand, institutional actors’ mistrust towards youth has fuelled policy panic about ‘youth bulge’[10] and violent extremism. The result has been disproportionate investment in security dominated measures, which address the symptoms of violent conflict rather than the root causes of the structural and psychological ‘violence of exclusion’ faced by young people.

‘The Missing Peace’

The most powerful and leading research on YPS is the independent progress study on UNSCR 2250, called ‘The Missing Peace’.[11] On the basis of an in-depth study of on-ground youth-led peacebuilding organizations, it mentions that young peacebuilders feel that their relationship with the community and deep understanding of the local conditions is a strength compared to other actors such as government, aid agencies, security forces and religious leaders. This also debunks a huge myth; there is little reliable evidence for the widespread assumption that youth unemployment and violence are correlated.

Despite the challenges, young people across the globe are still demonstrating their leadership in PVE, post-conflict peacebuilding, and building resilience in humanitarian contexts. During outbreaks of violence and humanitarian crisis, young people are often the first responders who are able to reach areas that international actors cannot very easily. A recent study by One Young World found that every US$1 invested in young people participating in their programmes leads to US$13 of social value.[12]

“We cannot hope to make progress in conflict situations if we have not put in place the structures, the funding, the mechanisms and mindsets for meaningful youth inclusion during peacetime. – H.E. Mrs Maria Fernanda Espinosa Garces, President of the UN General Assembly”

The challenges are galore. Currently the share of global giving that goes to peace and security work with children and youth is only 0.05 percent as per the Peace and Security Funding Index, despite high potential social return on investments in youth.[13] Moreover, most youth-led organisations depend heavily on volunteers (operate with 97 percent volunteers including staff and members) and half of the organisations that responded to the global survey operate with less than US$5,000 per year.[14] This makes, young peacebuilders spend considerable time in fund raising for the survival of their initiatives, which becomes a huge trade-off in implementation, evaluation, scale and replication.

The support system and progress is negligible. In 2013, India became the first country in the world to make corporate social responsibility (CSR) mandatory, under the Company Act (2013) and Section 135. On an average, approximately US$2 billion are being spent annually by corporates towards social welfare activities in last three years. But in schedule VII, this act has a limited prescription. Of eight fields for such funding, ‘peacebuilding’ is not one. So, the peacebuilding projects either don’t get support from CSR or need to presented in the possible closest category of ‘education’, even when peacebuilding being much more than this.

Even after importance and urgency of action to advance YPS agenda nationally, there has been only one half-a-day consultation organised so far by Ministry of Youth Affairs & Sports in India on UNSCR 2250 in August 2017. It is obvious that one such consultation in four years is nowhere close to being sufficient to bring attention to youth, peace and security in India.

Plugging the Policy Gap

India needs to improve its ‘commitment-in-action’ to transform the deeply-rooted attitudes and practices for systemic change. While, the Government of India is on the verge of coming up with the National Youth Policy 2020, it along with other stakeholders can definitely do more. Current holistic youth development related funding commitments are scarce. The annual budget of the Ministry of Youth Affairs & Sports for 2018- 19 was ₹2,000 crore (US$285 million), with only ₹620 crore (US$87 million) under Department of Youth Affairs, roughly translating to an expenditure of only ₹16 (US$0.22) on a youth in an year. Further, one way to support youth-led peacebuilding organisations is to set-up innovative and youth-friendly funding mechanisms. Overall, the independent progress study on UNSCR 2250 suggests three mutually reinforcing strategies to various stakeholders:

- Invest – in young people’s capacities, agency and leadership; through adequate funding and opportunities essential to drive capacity building.

- Include – youth meaningfully, politically & economically; peace education; transform the systems which reinforce or encourage exclusion; get rid of any structural barriers which limit youth participation; reintegration; protection; rule of law.

- Partner – in implementation; via coalitions, policy frameworks and mechanisms for dialogue & accountability.

It is crucial to act on the principles of local agency and youth leadership in peacebuilding.[15] The energy, creativity, and commitment which youth demonstrate, deserve more than just ‘being included’ or ‘participation’ in peacebuilding. For example, there is an incipient effort from young peacebuilders, under leadership of Youth for Peace International to form national coalitions on youth, peace and security in India.[16] The decision makers need to support such coalition-building efforts to advance YPS work in India and having youth-led organizations in a leadership role.

End Notes

[1] United Nations Security Council Resolution 2250, 9 December 2015, http://unscr.com/en/resolutions/2250, Accessed on 15 January 2020.

[2] A Guide To Un Security Council Resolution 2250 (2016), UNOY Peacebuilders, http://unoy.org/wp-content/uploads/Guide-to-SCR-2250.pdf, Accessed on 15 January 2020.

[3] Incidents of major communal riots include [Bombay (1992), Bangalore (1994), State of Gujarat (2002), Muzaffarnagar (2013), Saharanpur (2014), State of Assam (2014), Malda (2016), and Baduria (2017). “India: Incidents of Communal Violence – Some Data, Graphs and Statistics 2012-2017”, South Asia Citizens Wire, 3 July 2018, http://www.sacw.net/article13795.html, Accessed on 28 January 2020.

[4] Annual Report 2018-19, Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports, Government of India, https://yas.nic.in/sites/default/files/Annual%20Report%20%28English%29%202018-19.pdf, Accessed on 15 January 2020.

[5] National Youth Policy (India) 2014, https://yas.nic.in/sites/default/files/National-Youth-Policy-Document.pdf, Accessed on 15 January 2020.

[6] World Development Report 2011, World Bank, https://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTWDRS/Resources/WDR2011_Full_Text.pdf, Accessed on 15 January 2020.

[7] Global Burden of Armed Violence (2011), Geneva Declaration Secretariat, p.81, http://www.genevadeclaration.org/fileadmin/docs/Global-Burden-of-Armed-Violence-full-report.pdf, Accessed on 15 January 2020.

[8] R Coomaraswamy, Preventing Conflict, Transforming Justice, Securing the Peace: A Global Study on the Implementation of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 (New York, 2015), https://www2.unwomen.org/-/media/files/un%20women/wps/highlights/unw-global-study-1325-2015.pdf?v=1&d=20160323T192435, Accessed on 15 January 2020.

[9] Young People’s Participation In Peacebuilding: A Practice Note (2016), http://unoy.org/wp-content/uploads/Practice-Note-Youth-Peacebuilding-January-2016.pdf, Accessed on 15 January 2020.

[10] Iftikhar Gilani, “Youth bulge may become a bane for India, says US intel report”, DNA, 14 January 2017, https://www.dnaindia.com/india/report-youth-bulge-may-become-a-bane-for-india-says-us-intel-report-2292254. Accessed on 29 January 20120.

[11] The Missing Peace: Independent Progress Study on UNSCR 2250 (2018), https://www.youth4peace.info/system/files/2018-10/youth-web-english.pdf, Accessed on 15 January 2020.

[12] One Young World Annual Impact Report (2017), https://www.oneyoungworld.com/news-item/2017-impact-report, Accessed on 03 February 2020.

[13] Peace & Security Funding Index (2018), https://peaceandsecurityindex.org/year/2018/populations/children/, Accessed on 03 February 2020.

[14] UNOY Peacebuilders and SFCG. Mapping a Sector: Bridging the Evidence Gap on Youth-Driven Peacebuilding (The Hague, 2017), http://unoy.org/wp-content/uploads/Mapping-a-Sector-Bridging-the-Evidence-Gap-on-Youth-Driven-Peacebuilding.pdf, Accessed on 15 January 2020.

[15] Translating Youth, Peace & Security Policy into Practice: Guide to kick-starting UNSCR 2250 Locally and Nationally, UNOY Peacebuilders and Search for Common Ground (2016), http://unoy.org/wp-content/uploads/2250-Launch-Guide.pdf, Accessed on 15 January 2020.

[16] Youth for Peace International, http://yfpinetwork.com/, Accessed on 03 February 2020

(Mridul Upadhyay is the co-founder of Youth for Peace International and Asia Coordinator of United Network of Young (UNOY) Peace builders. He has more than a decade of voluntary and full-time experience in the development sector and advancing the Youth, Peace & Security (YPS) agenda in the last four years. His work has components of policy advocacy, programming and capacity development of individuals, organisations, religious actors, UN agencies and governments. He also contributes to the youth-led YPS programming efforts of Search for Common Ground, KAICIID and United States Institute of Peace as a council member of their Global Youth Advisory Councils. This analysis is published as part of Mantraya’s ongoing “Women and Youth in Peace and Security” project. Mantraya analyses are peer-reviewed publications.)