MANTRAYA OCCASIONAL PAPER #10: 11 OCTOBER 2024

EKAMPREET KAUR

Abstract

This paper examines the evolution of the Taliban’s foreign policy by comparing their first regime (1996-2001) to their current administration (2021-present). The paper integrates qualitative analysis of Taliban statements and expert interviews with quantitative assessments of diplomatic interactions. The findings indicate that while the Taliban’s core ideology, rooted in a stringent interpretation of Sharia law, remains largely unchanged, their foreign policy now seeks increased diplomatic engagement, to enhance economic relations. By analysing internal dynamics within the Taliban, external pressures, and global geopolitical changes, the paper finds a clear transition from the isolationism characteristic of the first regime to a more pragmatic approach. This shift is primarily driven by the pressing domestic need for economic stability and the pursuit of international legitimacy for the Islamic Emirate. At the same time, however, the Taliban’s foreign policy objectives are still constrained by their ideological commitments, relationships with transnational terror groups, and security concerns, which often translates into tensions between tactical flexibility and strategic rigidity.

INTRODUCTION

The capture of Kabul by the Taliban on 15 August 2021, again turned attention to this violent radical Islamist force, which has since its founding in the mid-1990s continued to experience significant changes. The Taliban formed their first government (hereafter, Taliban 1.0) in 1996 after rising from the chaos of post-Soviet Afghanistan. The strict application of its version of Sharia (Islamic law) and an isolationist foreign policy defined this government. Ousted by Western intervention, there followed two decades of insurgency before regaining state power in 2021. The Taliban is now in its second chapter (hereafter, Taliban 2.0). Several diplomatic initiatives and visible changes in the group’s foreign policy stance have been a major part of this new era. The divergent approaches to foreign policy used during these two stages are reflections of shifts in the international political landscape as well as the internal workings of the Taliban.

In this contribution is offered a comparative analysis of the foreign policy development of the Taliban. It offers insights for policymakers, scholars, and analysts who want to understand the complexities of Afghan geopolitics and the implications of Taliban policies for regional stability and global security. Insight into the strategic adjustments made by the Taliban and the possible effects on their future interactions with other countries is advanced by analysing the visible changes in their foreign policy. These in turn will affect regional diplomacy and international counterterrorism initiatives.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

The research questions guiding this contribution are thus:

1. Has there been a change in the Taliban’s foreign policy between the first and second regimes?

2. What external and internal factors have influenced these changes?

3. What role has international isolation/pressure or engagement played in shaping the Taliban’s foreign policy during both periods?

4. In what ways have the Taliban’s strategies towards international recognition and legitimacy changed?

RELATIONS WITH REGIONAL POWERS

This section examines how the Taliban’s relations with regional powers changed between their 1.0 and 2.0 versions. It emphasises how they moved from ideological isolationism to what appears to be a more pragmatic diplomacy with neighbours such as Pakistan and Iran. This analysis provides insights into the complex regional dynamics of Afghanistan by examining the main drivers of these shifts, including the quest for international legitimacy, economic strengthening, and security.

Taliban 1.0’s Relations with Neighbouring States

Significant animosity existed between Iran and the Taliban 1.0, primarily as a result of deep ideological divides and territorial issues. As a fervently Sunni Islamist state, Afghanistan under Taliban 1.0 refused to recognise the government of Iran, a country with a Shiite majority, viewing it as a heretical enemy (Goodson, 2001). Conflicts over vital resources—most especially control of the Helmand River, which flows from Afghanistan into Iran—exacerbated this ideological split (Slavin, 2001).

The 1998 death of Iranian diplomats in Mazar-i-Sharif at the hands of Taliban forces signalled a dramatic deterioration in Iran-Taliban ties. The incident, which claimed the lives of a journalist and eight Iranian diplomats, is commonly referred to as the “Iranian diplomats crisis” (Mir, 2021). Iran accused the Taliban of deliberately targeting its citizens, escalating tensions between the two nations to the point that war seemed imminent. In response, Iran increased its support for anti-Taliban forces, further widening the ideological and geopolitical rivalry between the two.

In contrast, Pakistan, besides offering military, financial, and diplomatic support, was one of Taliban 1.0’s principal allies. Still, the two countries also had a complicated and occasionally tense relationship. Pakistan was concerned about the possibility of Pashtun separatism within its borders due to the Taliban’s strong Pashtun ethnic identity (Saikal, 2012). As Professor Marvin G. Weinbaum, Director of Afghanistan and Pakistan Studies at Middle East Institute, observes, “Pakistan’s role in the 1990s was to ensure the cooperation of Afghanistan by essentially installing a Taliban government that would be beholden to them. However, what they discovered was that it’s not so easy to control Afghans, who resent being dictated to by Pakistan” (M. Weinbaum, personal communication, August 7, 2024). Further strain between the two nations was brought about by disagreements over the Durand Line boundary and the Taliban’s accommodation of terrorist organisations that carried out operations within Pakistan (Nawaz, 2008).

The establishment of economic links with surrounding states or the growth of the Afghan economy was not given priority by the Taliban 1.0 leadership, which placed more emphasis on maintaining political and military control within the nation (Rashid, 2000). Kabul’s economic policy remained restricted, even in its relations with Pakistan, with diplomatic ties comparatively better. Instead of actively encouraging cross-border trade or the development of infrastructure, the regime mostly depended on opium cultivation, customs duties, and assistance from Pakistan (Goodson, 2001).

The main factors influencing Taliban1.0’s regional ties during this time were a set of fundamental goals that emphasised an overarching strategic stance. The ideological conflict at the heart of the Taliban’s foreign policy was their attempt to establish the supremacy of their ultraconservative Sunni Islamist ideology, particularly against Shiite Iran (Maloney, 2013). The Taliban stressed establishing and retaining control over Afghanistan’s borders and resources, even when doing so harmed relations with surrounding countries. This ideological motivation was matched by a relentless focus on territorial control (Rashid, 2000).

Reducing outside influence in Afghanistan was another of Taliban 1.0’s main goals. Perceiving such developments as challenges to their authority and regional aspirations, they were resolved to thwart the rise of pro-Indian or pro-Iranian regimes (Saikal, 2012). The Taliban also needed Pakistan’s continued political, economic, and military support to maintain power (Coll, 2004). Additionally, the Taliban deliberately used their partnership with Pakistan to crush opposition groups that posed a threat to their regime and suppress internal rivals (Nawaz, 2008). During their first rule, the Taliban’s approach to regional affairs was shaped by these interconnected objectives, revealing a regime focused more on maintaining power than building relations with neighbouring states.

Taliban 2.0: Pragmatic Regional Diplomacy and Engagements with Pakistan and Iran

Taliban 2.0 has adopted a more pragmatic approach to regional diplomacy, prioritising stability and economic cooperation. According to Maizland (2023), the three main goals of Taliban 2.0’s regional diplomacy are to gain international legitimacy, secure economic support, and maintain internal cohesion. Their attempts to interact with regional powers, such as Iran and Pakistan, demonstrate this pragmatic approach, reflecting a recognition of the interconnected nature of regional stability and economic development. According to Rubin (2022), the revised diplomatic efforts are part of a larger plan to present Afghanistan as a possible centre for connectivity and trade in the region. This strategy, which is a major shift from their prior isolationist posture, makes use of Afghanistan’s geographic location to draw support and investment.

The dynamics under Taliban 2.0 point to a more nuanced strategy by Pakistan, one that strikes a balance between encouraging moderation and encouraging foreign engagement. Yusuf and Zaidi (2022) claim that Pakistan’s attitude has changed as a result of the need to safeguard its own security interests while simultaneously acknowledging the importance of integrating the Taliban into the international community. This is demonstrated by Pakistan’s attempts to manage its ties with Taliban 2.0 to lessen the threat presented by the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). As Weinbaum notes, Pakistan initially hoped that the Taliban’s return to power in 2021 would secure greater cooperation in countering these groups. However, Pakistan’s expectations have been unmet, leading to a deterioration in relations, though both sides recognise the need to avoid outright conflict (M. Weinbaum, personal communication, August 7, 2024).

A major aspect of the present relationship between Taliban 2.0 and Pakistan is economic cooperation, which reflects the larger regional forces at work. Ahmad and Khan (2022) discuss the prospects of extending the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) into Afghanistan, highlighting the Taliban’s expressed interest in joining this initiative. The Taliban’s approach to integrating Afghanistan into regional economic networks is changing, as seen by their involvement. By creating economic opportunities, these networks may help stabilise the nation.

Conversely, there has been a noticeable change in Taliban 2.0’s relationship with Iran from their previous hostilities. Since 2021, the two sides have adopted a pragmatic stance despite their persistent ideological disagreements, prioritising their shared interests over their historical animosities (Milani, 2021). In particular, economic cooperation has grown to be a key component of their relationship, with Iran becoming one of Afghanistan’s biggest commercial partners. The improvement of bilateral ties can be attributed in large part to this increased economic interdependence (Fazeli, 2022). Beyond the economy, cooperation in the field of security has grown to be essential. In their joint efforts to counter the Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP), the Taliban and Iran have come to an unspoken understanding that pragmatic concerns have taken precedence over long-standing grievances (Watkins, 2022).

With 218 diplomatic engagements with Taliban 2.0 in three years, Iran has demonstrated a significant and growing level of engagement. From 32 engagements in the first year to 67 in the second and 119 in the third, there was a notable increase in engagements, indicating that the diplomatic relationship was developing and becoming more intense (Zelin, 2024). Even a military attaché has been dispatched by Taliban 2.0 to their Tehran embassy.

The pursuit of legitimacy and international recognition is at the centre of Taliban 2.0’s regional diplomacy, which is motivated by a combination of pragmatic and ideological goals (Mir, 2022). This need for recognition directly influences their domestic and foreign policies and is closely tied to their pursuit of economic support, particularly through engagement with regional powers (Rubin, 2022). Since internal security issues influence their relations with surrounding nations, security considerations and the goal of stability are also essential components of their strategy (Giustozzi, 2022). Furthermore, the Taliban’s desire to turn Afghanistan into a hub for regional trade highlights their larger economic objectives, underscoring the necessity of integration into regional economic networks for long-term stability and governance (Gul & Ahmad, 2023).

Comparative Analysis of Taliban 1.0 and 2.0’s Regional Diplomacy

The Taliban adopted an isolationist strategy during their first term in power. Only Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates formally recognised their government. Taliban 1.0’s emphasis on ideological purity caused it to become isolated and strained its ties with most of its neighbours (Maley, 2022). Taliban 2.0, on the other hand, has taken a more practical and outward-looking diplomatic approach, motivated by the need for financial backing and international legitimacy. In contrast to their previous strategy, the new government has cultivated broader relationships with regional players to meet these needs (Mir, 2022).

A change in the Taliban’s regional diplomacy is also evident in their relationship with Pakistan. The Taliban relied significantly on Pakistan for international backing and representation during their first government, and Islamabad used this link to obtain “strategic depth” against India (Saikal, 2023). But under their present leadership, Taliban 2.0 have worked to retain cooperative relations with Pakistan while simultaneously attempting to claim more independence.

Taliban 2.0’s relationship with Iran has seen the most noticeable change. Relationships with Tehran were strained during their first administration because of sectarian tensions and Iran’s backing of the Northern Alliance. But under their present leadership, the Taliban 2.0 have turned to pragmatism, identifying points of agreement on things like opposition to ISKP (Milani, 2021). Professor Weinbaum summarises, “In comparing the two periods, the first Emirate never really settled down as it was a wartime government, while the current government feels far more secure. The Taliban’s diplomatic contacts today are much more professional compared to the 1990s when embassy interactions were informal and unprofessional” (M. Weinbaum, personal communication, August 7, 2024).

RELATIONS WITH MAJOR POWERS

From their first term of government (1996–2001) to their current administration (2021–present), the Taliban have significantly changed their approach to international affairs. This section examines how their foreign policy changed during these two different eras, concentrating on their dealings with major powers.

Taliban 1.0’s Relations with Major Powers

With the fall of the Soviet Union and the “unipolar moment” of American dominance in world affairs, the international system underwent substantial changes that coincided with Taliban 1.0’s ascent to power in 1996. Kabul’s interactions with major powers remained restricted and generally hostile despite these changes. This isolationist tendency was based on their ideological framework, which prioritised implementing their interpretation of Sharia over building international linkages. They had particularly tense relations with the United States. U.S. oil firms’ initial attempts at cooperation gave way to growing antagonism as worries about violations of human rights and backing for terrorist organisations increased.

Taliban 1.0’s foreign policy, such as it was, revolved largely around economic imperatives, particularly the desire to develop Afghanistan’s natural resources and infrastructure (Matinuddin, 1999). The necessity to rebuild a nation devastated by war and attain financial stability motivated the regime’s desire for economic development, which they tried to do through modest levels of foreign economic engagement. This explains the early willingness to discuss pipeline projects with American oil corporations.

Direct engagement with neighboring Russia was limited, and much of the relationship was shaped by historical context. Many of the factions that later formed the Taliban, such as the Haqqani network, were actively involved in fighting the Soviet Union during the 1980s. Ahmad Seyar Daudzai, former acting Ambassador of Afghanistan to the UAE, pointed out that the legacy of the war with the Soviet Union played a role in the low level of engagement. (A. S. Daudzai, personal communication, August 16, 2024).

There was little interaction and a great deal of strain in the relationship between Taliban 1.0 and the United States. At first, the United States saw the Taliban as a potential source of stability in the nation ravaged by conflict (Rashid, 2010). However, this opinion quickly changed due to widespread human rights abuses, especially those directed against women, as well as the Taliban’s decision to offer a haven to al-Qaeda (AQ). The United States placed sanctions on the Taliban regime in 1999 due to their sponsorship of international terrorism (U.S. Department of State, 2001).

For its part, India adopted a strong posture of non-engagement and outright resistance to Taliban 1.0, in contrast to certain other regional actors. Since “that wasn’t the legitimate government of the day,” India declined to acknowledge the Taliban administration and supported the Northern Alliance under the leadership of Ahmad Shah Massoud (Paliwal, 2017; S. D’Souza, personal communication, August 20, 2024). Ideological differences, geopolitical regional interests, and security concerns all influenced this policy. India’s national security was directly threatened by Taliban 1.0’s close relations with Pakistan and their support of militant groups in Kashmir (Basu, 2007).

Taliban 2.0’s Relations with Major Powers

Since 2021, Taliban 2.0 have adopted a notably different diplomatic tack than previously. Maley (2022) claims that due to their quest for legitimacy and financial assistance, the group has demonstrated a stronger willingness to interact with the international community. The way they actively engage with different nations and international bodies illustrates this shift.

Taliban 2.0’s changing relationship with India is a prime example of this realistic foreign policy shift. India has always opposed the Taliban and it backed the Northern Alliance during Taliban 1.0; but under the current Taliban 2.0, New Delhi is willing to interact with Kabul (Pant & Iwanek, 2022). Taliban 2.0 has reciprocated. Taliban spokesman Suhail Shaheen openly praised India’s diplomatic and economic involvement in Afghanistan in 2021, highlighting the group’s wish to foster more positive relations, even with those that had previously opposed their rule (Bhattacherjee, 2021). Significantly, Taliban 2.0 have publicly spoken to India’s security concerns by assuring that Afghan soil will not be used for terrorist activities against any nation (Gul, 2021).

The reality of this pledge remains to be tested, but it has been made. Professor Shanthie D’Souza, founder and president of the Mantraya Institute for Strategic Studies, referred to this as “a new phase of engagement with the Taliban”, marked by India’s return to Afghanistan in June 2022 when it reopened its mission and resumed aid to various humanitarian agencies, despite not formally recognizing the Taliban regime (S. D’Souza, personal communication, 20 August 2024).

The position of major world powers such as the United States complicates the quest for international legitimacy. Washington has declined to formally recognise the Kabul government, citing human rights concerns, especially those affecting minorities and women, as well as the Taliban’s inability to form an inclusive government. Formal recognition is further hampered Taliban 2.0’s ongoing affiliations with terror groups, its public commitments notwithstanding. U.S. interaction with Taliban 2.0 is limited to humanitarian relief and counterterrorism. American policy towards Taliban 2.0 continues to rely heavily on economic distancing, such as sanctions and the freezing of assets held by the Afghan central bank (Thomas, 2022).

Sadiq Amini, former political assistant at the U.S. Embassy in Kabul, mentioned that “this cautious engagement is rooted in a history of diplomatic interactions, beginning with the establishment of the Taliban’s political office in Doha in 2013, which the U.S. facilitated to create a platform for negotiations” (S. Amini, personal communication, August 19, 2024). The frequency of interactions since the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan has decreased over time, which is indicative of Washington’s growing focus on more pressing international issues such as the situation in Ukraine, the Middle East, and competition with China.

The fact that some major powers, including China and Russia, have maintained a more regular diplomatic presence in comparison to the United States highlights the complicated and dynamic character of Taliban 2.0’s international ties. Understanding these geopolitical realities, the Taliban have deliberately modulated their relations as necessary and appropriate. They have aligned with China to further their broader geopolitical objectives while also trying to reassure the United States by portraying themselves as counterterrorism allies (S. Amini, personal communication, August 19, 2024). This dual strategy illustrates Taliban 2.0’s more realistic manoeuvring in the international arena while vying for the recognition that is still essential to achieving their larger goals.

As might be expected, Russia and Taliban 2.0 have a more nuanced and strategic relationship. Although it hasn’t formally hosted a meeting with the Taliban yet, Russia has maintained a consistent level of diplomatic engagement, with some 95 interactions over the course of the three years (Zelin, 2024). There has been an increase in interest in Taliban w.0 diplomacy, as seen by the number of interactions, which went from 18 in the first year to 23 in the second and 54 in the third. In addition, Russia hosted 53 meetings, which made it one of the more popular destinations for Taliban diplomatic visits outside of Afghanistan and Qatar.

According to Daudzai, the alliance is motivated by Russia’s competition with the West and worries about the terrorism threat spreading to Central Asia. He states, “The relationship with Russia is more tactical than strategic, primarily because there are long-term grievances. Russia engages with the Taliban because the West is not comfortable with countries dealing closely with the Taliban without resolving humanitarian issues and women’s rights” (A. S. Daudzai, personal communication, August 16, 2024). Russia has greater geopolitical interests in the region, and its engagement with the Taliban also intends to stop the ISKP from expanding into Central Asia. The Taliban received economic backing, including subsidised fuel and essential commodities such as wheat, as well as diplomatic legitimacy in exchange (Ibid.).

Taliban 2.0 regime’s ability to engage with non-Islamic countries such as Russia marks a significant shift from the previous approach, where their international relations were limited to a few Islamic countries. Daudzai highlights this shift by noting, “One other advantage that Taliban 2.0 has is that they have the ability now to engage with some non-Islamic countries like China. This is something they did not have in their previous incarnation in the 1990s” (Ibid.). This evolution in the Taliban’s foreign policy reflects a broader pragmatism in their international engagements, driven by both geopolitical and economic considerations.

China’s relationship with them has been marked by cautious pragmatism. China has partnered with the Taliban to keep Afghanistan from serving as a haven for terrorists hostile to China, as it is particularly concerned about the possible threat posed by Uyghur militants, notably those connected to the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM). China has offered diplomatic engagement and economic cooperation, with a focus on Afghanistan’s resource-rich landscape, including potential investments in mining and infrastructure projects. However, China’s investments remain tentative due to the volatile security situation and the unpredictable nature of Taliban governance. This partnership also fits with China’s larger regional strategy, which aims to strike a balance between its relationships with other regional powers like Pakistan and Central Asian nations and its engagement in Afghanistan. This strategic engagement allows China to maintain its influence while remaining adaptable to the evolving situation in Afghanistan (Siddiqui, 2023).

China emerged as the country with the highest number of diplomatic engagements with the Taliban, totalling 276 interactions over three years (Zelin, 2024). Before sharply rising to 135 in the third year, the engagement level was steady in the first two (71 and 70). Due to two key criteria, Daudzai emphasises that “China is one of the countries that do have extensive diplomatic contacts with the Taliban (A. S. Daudzai, personal communication, August 16, 2024).” China is keen to investigate investment prospects in Afghanistan, namely in the mining industry, given the crucial minerals found in the country that are essential for both climate action and the Fourth Industrial Revolution. On the other hand, China is concerned about the insecurity that arises from Afghanistan, particularly about the Uyghur community and the possible volatility in Xinjiang. Daudzai concludes that “China is very disappointed” in the Taliban’s unwillingness to drive out ethnic Uyghurs from Afghanistan (Ibid.).

Comparative Analysis

From their first term of office (1996–2001) to their current tenure (2021–present), the Taliban have undergone a significant shift in how they handle great power rivalry and interact with foreign entities. This analysis highlights key differences in their strategies towards major global powers, particularly focusing on Sino-US and Indo-Pak rivalries.

Taliban 1.0 had no interaction with China during their first term in power and remained antagonistic towards the US. Tensions with the US were heightened by the regime’s harbouring of Osama bin Laden, ideological rigidity, and isolationist policies. In contrast, Taliban 2.0 has a different strategy. The current government has made a concerted effort to court Chinese backing and investment, indicating a practical move to interact with world economic powers. Their own desire to obtain funding and investments to stabilise Afghanistan’s weak economy is what motivates them to adopt this realist approach. In contrast to their earlier period of rule, Taliban 2.0’s outreach to the United States has changed, concentrating on unfreezing Afghan assets and pursuing international recognition. This shows a more strategic and balanced approach (Zhou, 2022).

Regarding the Indo-Pak rivalry, Taliban 1.0’s policies were heavily directed in favour of Pakistan. Saikal (2006) argues that the Taliban were effectively an extension of Pakistani influence in Afghanistan, which alienated India and other regional powers. Kabul’s approach limited its engagement with other regional actors and constrained its diplomatic options. Taliban 2.0, by contrast, has adopted a more nuanced stance in managing the Indo-Pak rivalry. While maintaining strong ties with Pakistan, the current regime has engagements with India, recognising its significant regional influence and economic power (Pande, 2022). This balanced approach reflects a more sophisticated understanding of global geopolitics and the benefits of engaging with multiple key players.

Economic interests now play a major role in Taliban 2.0’s foreign policy. The current leadership actively seeks foreign investment and aid to address Afghanistan’s economic difficulties, in contrast to their predecessors who did not emphasise economic growth in their foreign relations (Gul, 2023).

RELATIONS WITH TRANSNATIONAL TERRORIST MOVEMENTS

This section looks at how the Taliban’s ties to transnational terrorist movements have changed from their early 1990s ascent to their current position of power. It looks at how their ideology—which is based on rigid Islamist interpretations aligned with different violent radical Islamist organisations, especially AQ—has significantly influenced global events. The chapter illustrates the changes in the Taliban’s affiliations, relationship with terrorism, and attitude towards foreign fighters by contrasting Taliban 1.0 and 2.0.

Taliban 1.0’s Relationship with Transnational Movements

Besides AQ, Taliban 1.0 provided sanctuary to several other foreign terrorist organisations, such as the Eastern Turkistan Islamic Movement (ETIM), the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), and militant groups from Pakistan and Kashmir (Maley, 2001). About 80 training camps were located in Afghanistan by 1998; these were mostly in the eastern districts close to Pakistan. Between 1996 and 2001, according to U.S. intelligence, 10,000 to 20,000 fighters, were trained in the camps (Wright, 2006). A more modest estimate, provided by the 9/11 Commission Report (2004), placed the number to at least twelve by 1999, including Tarnak Farms, which is close to Kandahar.

Taliban 1.0 decided to give these organisations refuge for ideological, geopolitical, and financial reasons. In a strategic sense, these affiliations strengthened the Taliban’s opposition to the Northern Alliance, as well as economically generating income despite international sanctions (Coll, 2004).

Foreign counterterrorism initiatives faced substantial hurdles due to the internal security measures implemented by the Taliban, which included attempts at border control. Their reluctance to extradite Osama bin Laden in the face of international demand was indicative of their contradictory positions towards international counterterrorism campaigns (Rubin, 2002). These efforts were made more difficult by the destabilisation of the region brought about by the Taliban’s assistance for militant organisations in Kashmir and Central Asia (Nojumi, 2002).

The relationship between Taliban 1.0 and AQ was shaped by the Soviet-Afghan War (1979–1989). During the conflict, foreign militants who joined the jihad against the Soviets were known as “Afghan Arabs” and were instrumental in the formation of a transnational jihadist movement. Participation in the Soviet-Afghan War by numerous Taliban leaders and AQ members, including Osama bin Laden, fostered unity and understanding between them later on, facilitating their collaboration (Rubin, 2002). The defeat of the Soviet Union was viewed as a victory of Islam over a superpower, reinforcing the belief that a pure Islamic state could triumph over more powerful adversaries (Kepel, 2006).

AQ moved to Afghanistan in 1996 and discovered the Taliban to be a regime that shared similar values. Coll (2004) argues that bin Laden viewed Afghanistan as a secure location where AQ could organise activities, prepare agents, and expand its worldwide network without drawing attention from the outside world. The relationship developed based on shared ideologies and practical considerations, as well as interpersonal relations. Taliban 1.0 provided a safe operating base; AQ supplied cash and fighter training (Giustozzi, 2008). However, there were conflicts because some Taliban officials were concerned that bin Laden’s aggressive posture towards the West would draw outside attention (Burke, 2004). The connection ultimately proved fatal for Taliban 1.0, as they put their ties to AQ ahead of international calls for the extradition of Osama bin Laden to answer for the crimes of the 9/11 attacks (Rashid, 2010).

Taliban 2.0: Relations with Transnational Movements

The relationship with AQ persists in the era of Taliban 2.0, characterised by both continuity and change. Evidence points to continued cooperation between the Taliban and other terrorist organisations, notwithstanding Kabul’s public declarations that Afghan land will not be utilised for terrorist actions. Though Taliban 2.0 publicly disassociated itself from AQ to get international recognition, Mir (2022) contends that they are managing AQ’s presence, maintaining plausible deniability while benefiting from the group’s strategic capabilities.

With between 180 and 400 fighters, most of whom are based in the eastern and southern provinces of Afghanistan, AQ continues to have a substantial Afghanistan presence (Schroden & Batt, 2022). Sarah Adams, former Targeting Analyst with the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), explained how Taliban 2.0’s rapid recruiting has outpaced their training capabilities, which has led to the emergence of joint Taliban-AQ training camps. She pointed out that about 30,000 Taliban members have received training at AQ camps in Kandahar alone and that this integration seriously blurs the line between a state military force and a terrorist organisation because a sizable percentage of the Taliban’s forces now receive rigorous, high-quality training from AQ. She further indicated that current assessments estimate around 42 camps operated by AQ and affiliated groups, excluding those managed by the Islamic State Khorasan Province (S. Adams, personal communication, August 1, 2024).

In contrast to their relationship with AQ, Taliban 2.0 have a hostile relationship with the Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP). ISKP, an Islamic State affiliate, is a more extreme alternative to the Taliban and contests their control in Afghanistan. There are perhaps 4,000–6,000 ISKP fighters in-country, despite Taliban attempts to destroy them. Their tenacity and recruiting skills have allowed them to grow in power (Giustozzi, 2022; Gohel, 2022). ISKP has demonstrated its operational capability and posed a direct challenge to Taliban rule by expanding its attacks geographically throughout Afghanistan despite these efforts (Afghan Witness, 2024; Jadoon & Mines, 2022).

Taliban 2.0 has launched a vigorous counterinsurgency campaign intending to destroy the ISKP’s operational networks. These have been at least partially successful, and ISKP has weakened even as AQ has maintained its strength.

The relationship between Taliban 2.0 and Pakistani Taliban or Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) is more complex. While both groups share ideological foundations and historical ties, the Taliban’s need to maintain positive relations with Pakistan—a key regional power and a close ally—leads to a more nuanced approach (Mir, 2022). Although the Taliban have traditionally welcomed foreign fighters, they have changed their strategy and are now more cautious, distancing themselves from foreign elements to gain favour with the international community. Nevertheless, there has been uneven application of this policy (Watkins, 2022).

The situation is made more difficult by the Haqqani network, a potent Taliban faction. The network might potentially undermine Taliban 2.0’s position on foreign fighters because of its close ties to multiple violent radical Islamist groups (Felbab-Brown, 2021). The Haqqani network’s sway over the Taliban administration makes it difficult for the group to rule over or drive out foreign militants from Afghanistan.

Comparative Analysis between Taliban 1.0 and Taliban 2.0

As part of the 2020 Doha Agreement, Taliban 2.0 aims to present a more cooperative image by publicly pledging to prevent Afghanistan from serving as a base for international terrorism. In contrast, the Taliban 1.0 regime’s refusal to collaborate with international counterterrorism efforts, particularly in protecting AQ, resulted in the regime’s violent ouster. Taliban 2.0’s latest promises, claiming a reformed stance, remain open to question, in particular, due to the freedom of operation of numerous terrorist camps.

Further, Sarah Adams has drawn attention to the “Ghazwa-e-Hind” plan, which represents a significant shift from the strategy of Taliban 1.0, which exclusively relied on Pakistan as a safe haven. To gain local support and gradually turn the populace against the Pakistani government and military, Taliban 2.0, AQ, and Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS) are coordinating with the political party Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (JUI-F), led by Fazal-ur-Rehman. The initial goal of this new Taliban 2.0 strategy was to establish a territorial buffer in Pakistan’s tribal areas (S. Adams, personal communication, August 1, 2024).

According to Giustozzi (2020), internal factionalism, strategic considerations, and ideological commitments all influence Taliban 2.0’s counterterrorism tactics. While they may be more open to international cooperation, this openness is often selective and aimed at gaining legitimacy rather than genuinely combating all forms of terrorism.

Counterterrorism efforts in Afghanistan are further complicated by the substantial funding that numerous transnational terrorist groups receive from the drug trade. The links that the Taliban have with transnational groups have been significantly shaped by the illegal economy, especially drug trafficking. The Taliban 1.0 government allowed and even taxed the production of opium. But in 2000, they effectively outlawed the growing of opium, perhaps in an attempt to win over other countries (Felbab-Brown, 2006). The relationship between the drug trade and the Taliban 2.0 period is more complex. Although the Taliban leadership has publicly pledged to fight drug trafficking, there is a gap between official policy and reality since the rural populations and local commanders frequently profit from the trade (Felbab-Brown, 2022).

FACTORS INFLUENCING POLICY CHANGES

The political situation in Afghanistan and the dynamics of the region underwent a dramatic change in 2021 with the Taliban’s return to power. This section assesses the factors that have affected the foreign policy decisions and governance approach of the Taliban since their comeback. It looks at both internal and external factors.

Internal Factors

The following internal factors of the Taliban movement have played a crucial role in shaping their policies and governance strategies:

(i) Leadership Changes and Internal Policy Debates

The interplay between hardliners and moderates within Taliban 2.0 has greatly influenced internal dynamics and the direction of policy (Sayed & Hamming, 2023). Hibatullah Akhundzada, the supreme leader of the Taliban and a member of the hardline group, is a decisive factor. Many of Taliban 2.0’s policy decisions are motivated by Akhundzada’s emphasis on ideological purity and rejection of outside pressures (Watkins, 2022). Prominent individuals such as members of the Haqqani network, who are noteworthy for their unwavering ideological convictions and close ties to AQ, provide additional support for this harsh approach. A more moderate element, however, is represented by individuals such as Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, the leader of the negotiations with the United States. This group supports a more pragmatic strategy, acknowledging that good governance requires both international legitimacy and economic collaboration (Maizland, 2023).

Conflict between these groups has resulted in several policy shifts. Some of the most powerful Taliban commanders have openly criticised the country’s present course. This disagreement is indicative of a larger conflict within the Taliban as several leaders attempt to strike a compromise between their allegiance to extreme principles and their aspirations for international involvement and economic growth. But if social measures and diplomatic engagement are pursued too quickly, it could alienate the grassroots militants, who could see these changes as a betrayal of the fundamental values that gave rise to their insurgency. The situation is further complicated by the local affiliate of the Islamic State seeking advantage by accusing the Taliban of undermining the jihadist cause through contacts with foreign countries and policy compromises, which further complicates matters (Watkins, 2023).

The change in Taliban 2.0’s foreign ministers between the two regimes also highlights a shift in the international relations approach. Despite his lack of diplomatic experience and the severe limitations imposed by the extreme policies of Taliban 1.0, Wakil Ahmad Mutawakil, the foreign minister during the first regime, was instrumental in bridging the gap between Mullah Omar and the international community by using his English-speaking skills (Rashid, 2010; Maley, 2009). In contrast, the current foreign minister, Amir Khan Muttaqi, has greater expertise in government and negotiation, which reflects a more calculated attempt to interact with other countries and pursue economic cooperation. Even with these adjustments, though, Taliban 2.0’s internal and diplomatic policies are still shaped by the hardliners’ dominance, a major obstacle to bettering ties with other countries (Gannon, 2021; Maizland, 2023).

(ii) Shifts in Ideological Stance and Governance Models

Following the 9/11 attacks, Taliban 1.0 refused to turn over Osama bin Laden, displaying the confrontational and isolated foreign policy that prevailed throughout the first regime period (Felbab-Brown, 2022). Change was required strategically and ideologically during the 2001–2021 struggle against the Afghan government which was supported by external powers, notably those from the West. The group started to operate and communicate more pragmatically while still adhering to their fundamental Islamic beliefs. One significant shift was their approach to education. They had previously outright forbidden girls from attending school, but they gradually changed their minds and let certain girls’ schools function in regions under their jurisdiction (Jackson & Weigand, 2021). Though this has proved transitory, there remains the possibility of pragmatism reasserting itself.

During this time, the Taliban also refined their diplomatic and international relations strategies. In 2013, they took a big step towards gaining international credibility when they opened a political office in Doha, Qatar. This action made it easier to negotiate with the United States, which resulted in the Doha Agreement of 2020 (Watkins, 2021). When viewed via the constructivist lens, the Taliban’s activity can be understood as symbolic rather than merely strategic, as it aims to create a certain identity for the international community. The goal was to be seen as transforming from a militant Islamic organisation into an acknowledged political player.

The Taliban faced the difficulty of converting their insurgent philosophy into a workable style of governance upon their return to power in 2021. To present a more moderate front, they first made promises of inclusive governance and respect for women’s rights within an Islamist context. These early assurances have fallen by the wayside, a casualty of the ongoing internal conflicts between pragmatists and hardliners (Sayed, 2023).

The way the Taliban has evolved ideologically is demonstrated by their attitude to drug regulation. In 2000–2001, they successfully prohibited the growing of opium during their first administration. Their current position, however, is less clear-cut due to the necessity to retain support from rural populations as well as to generate revenue (Felbab-Brown, 2023).

Taliban 2.0 is more realistic and pragmatic in its interactions with the international community when it comes to foreign policy. Their attempts to interact with Western nations and other regional powers despite ideological differences are clear indications of this. The group’s leadership understands that to rule successfully, it needs both financial assistance and worldwide recognition (Zhou, 2023).

However, this practicality often clashes with their core ideological positions. It is difficult to strike a balance between international commitments and domestic ideological considerations, as seen by the Taliban’s inconsistent adherence to the Doha Agreement’s pledge to prevent terrorist organisations from using Afghan territory (U.S. Department of State, 2023).

External Factors

The complex interplay of external factors that have significantly influenced their policy decisions are:

(i) International Pressure and Diplomatic Engagements

The way the international community reacted to the Taliban’s takeover played a large role in how their policies developed. External pressure has taken a variety of forms, from negative international public opinion to economic sanctions. The United States and other Western nations implemented harsh economic sanctions when the Taliban took control, freezing billions of dollars in assets held by the Afghan central bank and stopping the majority of non-humanitarian aid (Byrd, 2023). The goal of these activities was to use economic pressure to sway Taliban policies, especially those that dealt with counterterrorism and human rights.

The increasing misogynism of Taliban 2.0 has only hardened the external stance. Sanctions have had a significant effect and have exacerbated Afghanistan’s dire economic situation. By mid-2022, 97 per cent of Afghans lived below the poverty line, according to UNDP (2022) figures. Taliban 2.0 have been forced to face the realities of international interdependence and governance as a result of this economic suffering, which may impact policy choices. Still, sanctions have an uneven record in influencing Taliban policy. While the economic pressure has compelled Taliban 2.0 to engage in some diplomatic efforts to ease sanctions, it has not led to significant policy shifts in key areas such as women’s rights or inclusive governance (International Crisis Group, 2022). In some cases, the sanctions may have reinforced the Taliban narrative of Western hostility, potentially hardening their stance on certain issues.

Another essential channel of international pressure on the Taliban has been diplomatic engagement. The Doha Agreement, which was signed in February 2020 by the U.S. and the Taliban, defined parameters for the latter’s behaviour and prepared the stage for further talks (U.S. Department of State, 2020). Despite its controversy, this accord established a framework for diplomatic pressure on matters such as intra-Afghan communication and counterterrorism. Following the takeover, numerous nations and international organisations have launched diplomatic initiatives to sway Taliban policy. As an illustration, discussions centered on humanitarian access and human rights have been aggressively pursued by the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA, 2023). The Taliban have also held diplomatic talks with other regional countries such as China, Russia, and Pakistan. These talks have frequently centred on security issues and business collaboration (Sayed & Hamming, 2023).

Social media and media coverage around the world have increased negative public opinion, which has put additional pressure on the Taliban. Even though their responses haven’t always been in line with world expectations, the Taliban have been obliged to address global concerns because of the public outrage over problems such as women’s rights, especially the education of girls. Part of the reason for Taliban 2.0’s early attempts to present a more moderate image after seizing power in 2021 was their awareness of the importance of global public opinion (Maizland, 2022).

(ii) Economic Conditions and Humanitarian Crises

The international community’s hostile reaction to the Taliban’s return to power has led to a major deterioration in Afghanistan’s economic situation. The financial crisis has gotten worse as a result of major institutions, such as the World Bank, the IMF, and even NATO, have suspended hundreds of millions of dollars in financial help. This has caused banks and remittance providers to stop offering their services. Afghanistan, which is already among the world’s poorest nations, greatly depends on international assistance to maintain its wider social infrastructure and healthcare system. With money drying up and misery spreading as the humanitarian crisis worsens, the absence of this crucial support has produced a serious economic dilemma (Moret, 2021).

This has impacted Taliban 2.0 policy choices. Foreign aid had previously made up 75% of the nation’s public spending. Combined with freezing of Afghan central bank assets held externally, the result has been daunting (World Bank, 2022). Taliban 2.0 have been compelled by this economic pressure to modify their governing strategy in a number of ways.

First, according to Byrd (2023), they have concentrated on boosting domestic revenue collection, especially from natural resources and customs taxes. This strategy shows an effort to assert economic sovereignty and lessen reliance on outside financial assistance. Second, despite their stated condemnation of the drug trade, the Taliban have found it difficult to reduce the opium industry in Afghanistan because of its importance to rural communities. Their strategy for combating the drug trade is still unclear, with a balance presently struck between global norms and local economic realities (Felbab-Brown, 2022). Third, the Taliban have sought to attract foreign investors, especially those from nearby nations. To induce investments, Kabul has stressed Afghanistan’s strategic location and mineral resources (Zhou, 2022).

Simultaneously with economic turmoil, Afghanistan has been dealing with a growing humanitarian catastrophe. Drought, the COVID-19 pandemic, and political unrest have combined to produce significant food hardship and displacement. 28.3 million people, or two-thirds of Afghanistan’s population, were projected by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA, 2023) to require humanitarian aid.

Over time, Taliban 2.0’s approach to this situation has changed. After being initially dubious of foreign aid agencies, the Taliban have progressively strengthened their collaboration with them as they have come to understand their vital role in meeting humanitarian needs (UNAMA, 2023). The Taliban have been cautious to phrase their acceptance of humanitarian help in a way that does not jeopardise their claims to legitimacy and sovereignty. They have opposed conditions being placed on aid and have insisted on having a say in how it is distributed (International Crisis Group, 2022).

(iii) Regional and Global Geopolitical Shifts

Since the Taliban’s first term in power (1996–2001), the global geopolitical environment has changed substantially, which has impacted present foreign policy approaches. A major change in the dynamics of the region was brought about by the U.S. withdrawal, which allowed other powers to increase their influence there (Maizland, 2022). The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), for instance, has increased Beijing’s stake in regional stability and growth (Zhou, 2022). Russia, seeing Central Asia as a part of its traditional sphere of influence, has attempted to regain its influence there (Stronski, 2021). Furthermore, because of their strategic interests, nations such as Pakistan, Iran, and India have sought to play a more active role in determining the future of Afghanistan (Sayed & Hamming, 2023).

In reaction to these geopolitics, Taliban 2.0 have taken a more measured and realistic approach to foreign policy in reaction to these geopolitical changes. They have made a concerted effort to broaden their international network of contacts beyond their customary dependence on Pakistan. They have explored better ties with Russia and have engaged with China, indicating a desire to join the BRI (Zhou, 2022; Stronski, 2021). They have also given regional diplomacy more weight, understanding how crucial Afghanistan’s neighbours are to the country’s stability and future economic opportunities (Watkins, 2022; Giustozzi, 2023).

The Taliban have continued to engage to some extent despite difficulties with Western nations, because they understand the value of prospective investment and assistance from the West. Their approach has involved a delicate balancing act between asserting independence and seeking international legitimacy (U.S. Department of State, 2023).

CONCLUSION

This contribution has traced the evolution of the Taliban’s foreign policy from their first period of rule (1996-2001) to their current regime (2021-present). The analysis highlights a significant transformation influenced by internal dynamics, external pressures, and shifts in the global geopolitical landscape. Despite the persistence of core ideological tenets, the Taliban’s international engagements now reflect a shift towards pragmatism, driven by the pressing need for legitimacy and economic stability.

There is a clear difference between the foreign policies of Taliban 2.0 and Taliban 1.0. The Taliban followed an isolationist policy during their first administration, which was characterised by a strict interpretation of Islamic law and little international interaction. Their foreign policy was primarily defined by a lack of enthusiasm for international diplomacy, which led to their recognition by just three nations and their extreme isolation from the rest of the world. This isolation was both a reflection and a consequence of their unwavering extremism, which made them pariahs on the international stage.

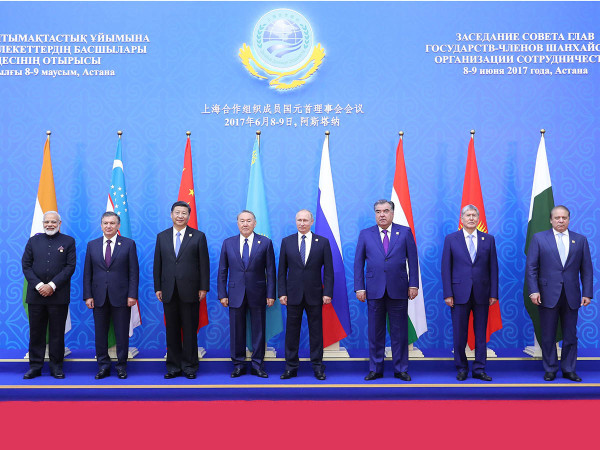

The current Taliban government, in contrast, has chosen a more nuanced and practical foreign strategy. Taliban 2.0 actively pursues diplomatic ties with a wide variety of nations, including powerful regional players and superpowers like China and Russia. Additionally, they have been successful in using Turkey, Malaysia, and Qatar as meeting places for diplomatic meetings. Over three years, Qatar hosted 306 meetings, more than any other country outside Afghanistan. Turkey hosted 59 meetings, with Malaysia facilitating 51 of them (Zelin, 2024). Such numbers reflect a realisation amongst the Taliban leadership that foreign involvement is a necessity to maintain their authority and sustain the Afghan economy. Their willingness to participate in international forums and negotiations underscores a desire for legitimacy and recognition that was absent during their previous rule.

The internal dynamics of the Taliban movement have played a crucial role in shaping their foreign policy across both periods of rule. These internal elements are mostly based on the group’s ideology, which is still firmly anchored in a rigid interpretation of Islamic law. Their worldview and decision-making processes have continuously been shaped by this ideological foundation, which frequently causes conflict between their interactions with other countries and their domestic image. The blend of pragmatists and hardliners in the Taliban’s leadership structure has had a big impact on how they approach foreign affairs. While the supreme leader, typically associated with the more conservative faction, wields considerable influence, voices from the political office often advocate for a more flexible stance in international relations.

The change in the Taliban’s strategy is much more noticeable in terms of the economy. Although Taliban 1.0 preferred to rely on a mix of illegal activities and minimal state intervention and showed little interest in international economic participation, the present administration has actively pursued foreign aid and investment. This economic pragmatism is largely driven by the dire situation in Afghanistan and the realisation that economic stability is essential for maintaining their power. The Taliban’s outreach to nations such as China, which has considerable economic influence, shows that they recognise that remaining isolated is no longer a long-term plan that would work and that doing so is necessary for their survival in a globalised world.

Between their two eras of rule, the strategic environment that the Taliban faced experienced substantial changes. This had a major impact on the approach to governance and policy decisions. Taliban 1.0 operated in a mostly isolated setting with little interaction with other countries. Only episodes such as the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas and growing connections to AQ brought international attention. In contrast, the current era is marked by intense international scrutiny, with every Taliban policy decision analysed and debated globally. Regarding matters such as women’s rights, inclusive governance, and counterterrorism, there are unambiguous international expectations. Taliban 2.0 have fallen short, their efforts to project a more moderate image abroad notwithstanding. Blocking the actual embrace of pragmatism remains a fundamental (if not odious) ideological stance.

The technological and information landscape has also transformed dramatically between the two periods of Taliban rule. Limited information flow and technical penetration in the late 1990s gave Taliban 1.0 a greater ability to control the media and keep the populace isolated from outside influences. Now, social media, the internet, and mobile technologies are widely available. The Afghan populace is more educated, more integrated, and more exposed to global standards and ideas. Taliban 2.0 consequently has been compelled to modify its strategy for information management and technology as a result of this change in the information landscape. Although they still aim to restrict access and content, their regulations show that they are conscious that total control over information cannot be achieved in the modern world. They have engaged in social media outreach and allowed for some level of technological access, albeit with restrictions.

The Taliban’s core ideology hasn’t changed much in spite of these adjustments. This consistency highlights the movement’s ingrained convictions, which still shape their perspective and methods of making decisions. Both eras have seen a persistence of internal power dynamics, notably the conflict between pragmatists and hardliners within the leadership, which has complicatedly shaped policy decisions. In addition, the Taliban’s foreign policy calculations continue to be heavily influenced by their relationship with Pakistan. The Taliban have always benefited strategically from this alliance, which is still essential to their regional strategy.

The study’s conclusions confirm the position that foreign policy has changed significantly from the extreme isolationism of Taliban 1.0 to a more measured pragmatism under Taliban 2.0. The Taliban have been forced to take a more practical stance in their foreign relations because of the urgent need for both economic stability and international recognition. Their participation in diplomatic forums, interactions with a wide range of international entities, and efforts to draw in foreign investment all highlight this turn towards pragmatism. These acts show a calculated shift from their prior strategy and reveal a more sophisticated grasp of world politics and economics.

Whether the underlying motives are genuine or but a cynical ploy remains to be seen. It is imperative to acknowledge that this pragmatic transition is not devoid of limitations. The fundamental security objectives and ideologies of the Taliban continue to have a significant impact on their policy choices. The group has a difficult time harmonising its stringent interpretation of Islamic law with international standards and expectations, especially when it comes to issues such as women’s and human rights. This ideological rigidity leads to contradictions between their international and domestic commitments, reflecting the ongoing tension between pragmatism and ideology within the Taliban leadership.

The security landscape, both domestic and regional, further complicates the Taliban’s foreign policy. Their relationships with terrorist groups and regional powers remain complex and sometimes contradictory, reflecting the delicate balance that must be maintained between their ideological roots, strategic interests, and international expectations. The Taliban’s foreign policy decisions will likely remain vexed by the conflict between upholding ideological purity and guaranteeing the regime’s survival.

REFERENCES

Afghan Witness. (2024). ISKP: Attacks against Taliban officials in Ghor and expansion of area of operations. https://www.afghanwitness.org

Burke, J. (2004). Al-Qaeda: The true story of radical Islam. I.B. Tauris.

Byrd, W. A. (2023). Solving Afghanistan’s economic crisis. United States Institute of Peace. https://www.usip.org/publications/2023/03/solving-afghanistans-economic-crisis

Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). (2023). The Islamic State threat in Pakistan: Trends and scenarios. https://www.csis.org

Coll, S. (2004). Ghost wars: The secret history of the CIA, Afghanistan, and Bin Laden, from the Soviet invasion to September 10, 2001. Penguin Books.

Crews, R. D., & Tarzi, A. (Eds.). (2008). The Taliban and the crisis of Afghanistan. Harvard University Press.

Felbab-Brown, V. (2006). Kicking the opium habit?: Afghanistan’s drug economy and politics since the 1980s. Conflict, Security & Development, 6(2), 127-149.

Felbab-Brown, V. (2021). Afghanistan’s security challenges under the Taliban. Brookings Institution.

Felbab-Brown, V. (2022). Pipe dreams: The Taliban and drugs from the 1990s into its new regime. Brookings Institution.

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/pipe-dreams-the-taliban-and-drugs-from-the-1990s-in to-its-new-regime/

Felbab-Brown, V. (2023). Afghanistan under the Taliban: Challenges and prospects. Foreign Policy at Brookings.

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/afghanistan-under-the-taliban-challenges-and-prospec ts/

Gannon, K. (2021, September 7). Taliban form all-male Afghan government of old guard members. Associated Press.

https://apnews.com/article/middle-east-pakistan-afghanistan-arrests-islamabad-d50b1b49 0d27d32eb20cc11b77c12c87

Giustozzi, A. (2008). Koran, Kalashnikov, and laptop: The neo-Taliban insurgency in Afghanistan. Columbia University Press.

Giustozzi, A. (2019). The counterinsurgency quandary in post-2001 Afghanistan. In S. M. D’Souza (Ed.), Countering insurgencies and violent extremism in South and South East Asia (pp. 225-237). Routledge.

Giustozzi, A. (2022). The Islamic State in Khorasan: Afghanistan, Pakistan and the new Central Asian jihad. Hurst & Company.

Giustozzi, A. (2023). The Taliban at war: 2001-2021. Oxford University Press.

Gohel, S. M. (2022). The evolution of the Islamic State Khorasan. Current Trends in Islamist Ideology, 30, 73-98.

International Crisis Group. (2022, August 15). Taliban policies risk de facto gender apartheid in Afghanistan.

https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-asia/afghanistan/taliban-policies-risk-de-facto-gen der-apartheid-afghanistan

Jackson, A., & Weigand, F. (2020). The Taliban’s war for legitimacy in Afghanistan. Current History, 119(813), 15-20.

Jackson, A., & Weigand, F. (2021). Rebel rule of law: Taliban courts in the west and north-west of Afghanistan. ODI.

https://odi.org/en/publications/rebel-rule-of-law-taliban-courts-in-the-west-and-north-wes t-of-afghanistan/

Jadoon, A., & Mines, A. (2022). The Taliban’s war against ISIS: How internecine jihadi competition shapes Afghanistan’s future. Combating Terrorism Center at West Point.

Kepel, G. (2006). Jihad: The trail of political Islam. I.B. Tauris.

Maizland, L. (2022, August 3). The Taliban in Afghanistan. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/taliban-afghanistan

Maizland, L. (2023, August 14). The Taliban in Afghanistan. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/taliban-afghanistan

Maley, W. (2001). The Afghanistan Wars.

Maley, W. (2009). The Afghanistan wars. Cambridge University Press.

Maley, W. (2022). The Taliban’s Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan: Challenges and Prospects. Asian Affairs, 53(1), 1-26.

Mir, A. (2022). Afghanistan under the Taliban: Regional recalibrations and domestic challenges. United States Institute of Peace.

Moghadam, V. M. (2002). Patriarchy, the Taleban, and Politics of Public Space in Afghanistan. Women’s Studies International Forum, 25(1), 19-31.

Moret, E. (2021, October 14). The role of sanctions in Afghanistan’s humanitarian crisis. The Global Observatory.

https://theglobalobservatory.org/2021/10/the-role-of-sanctions-in-afghanistans-humanitari an-crisis/

National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (2004). The 9/11 Commission report. W.W. Norton & Company.

Nojumi, N. (2002). The rise of the Taliban in Afghanistan: Mass mobilization, civil war, and the future of the region. Palgrave Macmillan.

Osman, B. (2016). The Taliban in transition: How Mansur’s death and Haibatullah’s ascension may affect the war (and peace). Afghanistan Analysts Network.

Rana, M. A., & Sial, S. (2022). Mapping the Taliban’s ties with Al-Qaeda and foreign fighters. Pakistan Institute for Peace Studies.

Rashid, A. (2010). Taliban: Militant Islam, oil and fundamentalism in Central Asia. Yale University Press.

Rubin, B. R. (2002). The fragmentation of Afghanistan: State formation and collapse in the international system. Yale University Press.

Sayed, A. (2021). The Taliban’s persistent war on Salafists in Afghanistan. Terrorism Monitor, 19(23), 7-10.

Sayed, A. (2023). The Taliban’s international diplomacy. United States Institute of Peace. https://www.usip.org/publications/2023/02/talibans-international-diplomacy

Sayed, A., & Hamming, T. (2023). The Taliban’s diplomatic dance: Engagement with regional powers. Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, 16(1), 35-49.

Schroden, J., & Batt, A. (2022). Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan: How much of a threat? Royal United Services Institute.

Sharan, T., & Bose, S. (2021). Afghanistan 2021: The Return of the Taliban. Skaine, R. (2002). The Women of Afghanistan Under the Taliban. McFarland & Company.

Stronski, P. (2021, January 19). Russia’s game in Afghanistan. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/01/19/russia-s-game-in-afghanistan-pub-83662

UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). (2023). Afghanistan humanitarian needs overview 2023.

https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/afghanistan/document/afghanistan humanitarian-needs-overview-2023

United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA). (2023). UNAMA mandate. https://unama.unmissions.org/mandate

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2022). Afghanistan: Socio-economic outlook 2022-2023.

https://www.undp.org/afghanistan/publications/afghanistan-socio-economic-outlook-202 2-2023

U.S. Department of State. (2020, February 29). Agreement for bringing peace to Afghanistan. https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Agreement-For-Bringing-Peace-to-Af ghanistan-02.29.20.pdf

U.S. Department of State. (2023, February 28). Special Representative for Afghanistan Thomas West on the situation in Afghanistan.

https://www.state.gov/special-representative-for-afghanistan-thomas-west-on-the-situatio n-in-afghanistan/

Watkins, A. (2021, November 2). An assessment of Taliban rule at three months. CTC Sentinel, 14(9), 1-14.

Watkins, A. (2022). An assessment of Taliban rule at one year. CTC Sentinel, 15(8), 1-20.

Watkins, A. (2023, April 11). What’s next for the Taliban’s leadership amid rising dissent? United States Institute of Peace.

https://www.usip.org/publications/2023/04/whats-next-talibans-leadership-amid-rising-di ssent

Watkins, A., & Ali, O. (2022). Digital Authoritarianism in Afghanistan: Increasing Restrictions on Internet Freedom. Afghanistan Analysts Network.

World Bank. (2022). Afghanistan economic monitor.

https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/0fa267944e2b004e4dba35e9b014bd89-031006202 2/related/Afghanistan-Economic-Monitor-14-April-2022.pdf

Wright, L. (2006). The looming tower: Al-Qaeda and the road to 9/11. Knopf.

Zelin, A. Y. (2024, August 6). Looking for Legitimacy: The Taliban’s Diplomacy Campaign. The Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/looking-legitimacy-talibans-diploma cy-campaign

Zhou, L. (2022, March 31). China’s tentative steps in Afghanistan: An economic and strategic wait-and-see approach. Stimson Center.

https://www.stimson.org/2022/chinas-tentative-steps-in-afghanistan-a-economic-and-strat egic-wait-and-see-approach/

Zhou, L. (2023, February 15). China’s Afghanistan dilemma. The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2023/02/chinas-afghanistan-dilemma/

(Ekampreet Kaur is a Research Intern with MISS. This Occasional Paper has been published as part of Mantraya’s ongoing “Fragility, Conflict, and Peace Building” and “Mapping Terror & Insurgent Networks” projects. All Mantraya publications are peer-reviewed.)