MANTRAYA ANALYSIS#33: 30 JANUARY 2019

BIBHU PRASAD ROUTRAY

Abstract

New Delhi’s strategic objectives in Myanmar remain important, yet ambigous. Firstly, the country is a lynchpin for India’s Act East policy. Secondly, it is a theatre where New Delhi is seeking to challenge the decades-old dominance of Beijing. And thirdly, Myanmar holds key to ending the remnants of the insurgencies in India’s northeast. To fulfil these objectives, New Delhi intends to boost the bilateral defence ties. While India’s Act East policy is a work in progress and the insurgents from North East India have not been dislodged from Myanmar’s territory, the ties between the defence forces of both countries have demonstrated signs of strengthening. For fulfilment of strategic objectives, however, there is a need to go beyond rhetoric and work on deliverables.

(Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, the commander-in-chief of Myanmar Army, during his visit to India,

meets India’s Army Chief General Bipin Rawat in July 2017. Photo Source: Ministry of Defence, Govt. of India.)

Introduction

Real or anticipated joint operations between the Indian Army and their counterparts in Myanmar hogs the media headlines quite regularly. In the past couple of years, such operations have reportedly taken place or are planned against the insurgent outfits operating in India’s northeast, who have found safe haven in the ungoverned spaces of Myanmar, primarily on the border region. The impact of such operations is not known, as the insurgents continue to be in Myanmar and their activities includes intermittent hit and run attacks, extortion and recruitment of new cadres. It appears that barring minor losses such as destruction of their camps and killing of handful of insurgents, they are under little pressure either from the surgical strikes by the Indian forces or from the joint and coordinated operations by forces from both countries. This shortcoming notwithstanding, defence cooperation between the two countries has witnessed considerable progress signifying the fact that India’s stakes in Myanmar is much larger and can continue even with the lack of achievement in curbing the activities of the insurgents of the northeast.

Flurry of Visits

Although New Delhi reversed its earlier Myanmar policy and started engaging with the military junta in the 1990s, the May 2012 visit of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh to the country initiated an era of deeper engagement between the two countries. Singh’s visit focused on bilateral economic relations. It was followed by then foreign minister Salman Khurshid and Air Chief Marshal N A K Browne visiting the country in November-December that year and the January 2013 visit by then Indian Defence Minister, A K Antony and the Indian Naval Air Chief.

In early September 2017, Prime Minister Narendra Modi visited Myanmar during three MoUs with respect to maritime cooperation were signed between both countries. Both countries ‘reviewed the security situation in their immediate neighbourhood and agreed upon the special need for enhancing closer bilateral cooperation in maritime security. They also agreed to foster mutually beneficial and deeper defence cooperation between the two countries.’[1]

Modi’s visit had been preceded by a four-day trip by Indian army chief General Bipin Rawat to Myanmar to discuss ongoing defense cooperation. In May 2017, Rawat met with a number of high-ranking officials, including Foreign Minister and State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi, military chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, Myanmar’s army chief, and other military officials. Two months later, in July 2017, Commander-in-chief of Myanmar armed forces, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing undertook a rare eight day visit to India. His schedule included meetings with the Prime Minister, Defence Minister, and the National Security advisor. Min Aung’s previous visit to India was in July 2015.

After two months, in September 2017, Myanmar’s Navy chief came calling to India. During his four-day trip (18-21 September) trip, Admiral Tin Aung San met India’s Defence Minister and the chiefs of India’s Army, Navy and Air force. The timing of the visit was important especially when Myanmar was seeking support for its actions on the Rohingya amid wide-spread criticism by several countries. India had provided ample indications that, like China, it is with the government of Myanmar and is willing to ignore the blatant abuse of human rights by the Myanmar military at the altar of real politik. The joint statement during Modi’s visit had referred only to the attacks by Rohingya terrorists in which Myanmar security forces had lost their lives and had made no references to the refugee crisis following the military operations carried out by Myanmar against the Rohingya.

In July 2018, External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj and her Myanmarese counterpart Wunna Maung Lwin met in New Delhi under the first ever Joint Consultative Commission (JCC) Meeting.

In September 2018, Indian Air chief Marshal B. S. Dhanoa visited Myanmar. The visit was followed up by a 78-member tri-services delegation of senior Indian military officials to Myanmar in December 2018. The visit was part of the first-ever exchange programme to enhance mutual trust between the forces of two countries guarding the border. Coinciding with the visit, 120 Myanmarese defence personnel came to India. Indian air force facilitated the travel of these personnel some of whom were travelling with their spouses.[2]

Capacity Building and More

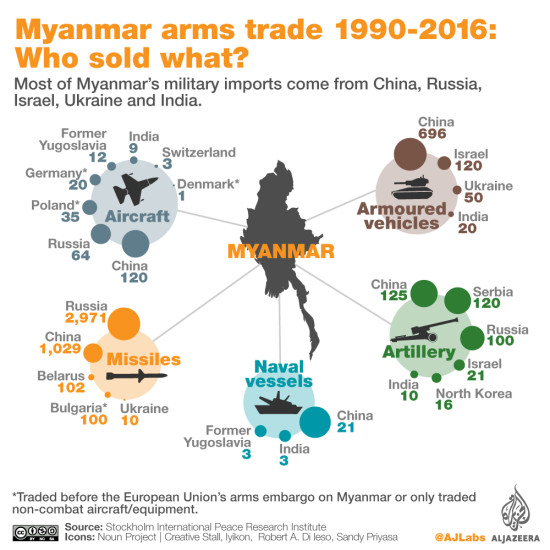

The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) has identified India as one of the five top sellers for weapons for the Myanmar military. The other countries are China, Russia, Israel and Ukraine.[3]Primarily directed at increasing its profile in Myanmar and seeking its cooperation against the northeastern insurgents, India has described its defence cooperation as a tool for ‘better border management’ and ‘capacity building’ exercise for the Myanmar military. In addition to the armed forces, it has also sought to assist the nascent Myanmar Navy.

Both countries conducted their first ever joint Naval exercise in March 2013. A frigate and a corvette of the Myanmarese Navy participated in the exercise in the Bay of Bengal, off the coast of Visakhapatnam. Subsequently, both navies engaged in coordinated patrol along the maritime boundary between Myanmar’s Coco Island and India’s Landfall Island, the northern most island of the Andaman group.[4]

In the same year, New Delhi agreed to assist Myanmar in building Offshore Patrol Vehicles (OPVs) in Indian Dockyards and also to train their pilots on Russian MI-35 helicopters. India supplied four Islander maritime patrol aircraft and naval gun-boats and a few 105mm light artillery guns, mortars, grenade-launchers and rifles. Over the years, the supply was expanded to include bailey bridges, communication gear, night-vision devices, war-gaming software, sonars, acoustic domes and directing gear. A $37.9 million deal for supply of lightweight torpedoes was finalised in March 2017.

During Myanmar Navy chief Admiral Tin Aung San’s September 2017 visit, New Delhi promised to consider supplying arms to Myanmar. Both sides discussed the supply of OPVs, which had remained unimplemented since A K Antony’s trip in 2013. Both countries also talked about ‘training Myanmar sailors on top of the courses taught to its army officers at elite Indian defense institutions’.[5]In contrast, a week back, Britain had announced that it was suspending its training programme for the Myanmar military, demanding it take steps to end the violence against civilians.

The bilateral ties were to further strengthen in the subsequent months. In November 2017, 31 officers from Indian and Myanmar military participated in the six-days India-Myanmar Bilateral Military Exercise (IMBAX-2017), which was organized in a newly established joint training node at Umroi in India’s Meghalaya state.[6] Hailed as the first military training exercise between both countries on United National Peacekeeping Operations (UNPKO), the exercise focused on training Myanmar forces on the conduct of such operations.

Continuing the trend, in March 2018, Myanmar participated in the MILAN naval exercises hosted by India at Port Blair. In the same month, between March 15 and 18, both sides held the sixth iteration of the India-Myanmar Coordinated Patrol Exercise (CORPAT) as scheduled. The third exercise of the month was the nine-day long India-Myanmar Naval Exercise 2018 (IMNEX-18). The exercise was held in the Bay of Bengal in two phases: a harbour phase at Visakhapatnam, followed by an at-sea phase. ‘On the Indian side, vessels included anti-submarine warfare corvette INS Kamorta , Shivalik (Project 17)-class frigate INS Sahyadri, and a Type 877EKM ‘Kilo’-class submarine, along with one helicopter and two Hawk advance jet trainer aircraft, and on the Myanmar side, vessels included the frigate UMS King Sin Phyu Shin and offshore patrol vessel UMS Inlay.’[7]

In July 2018, during Sushma Swaraj and Wunna Maung Lwin’s JCC Meeting, a joint statement announced that New Delhi would assist modernisation of Myanmar’s Army and Navy to upgrade military to military cooperation to the next level. The statement issued referred to India’s willingness to help Myanmar create ‘a national army, cooperation in the field of IT, in dealing with emerging security challenges, and military to military cooperation including in terms of training.’[8] The JCC also delved extensively on having better coordination and cooperation between their security forces to deal with insurgent groups, particularly those from the northeast region.

The second edition of the India-Myanmar bilateral army exercise, IMBEX 2018-19, was held between 14 to 19 January 2019 at Chandimandir Military Station that houses the headquarters of the Western Command. 15 officers each from the Indian and the Myanmar army participated in the six day exercise to train the Myanmar delegation for participation in United Nations peace keeping operations.[9]

Lack of Deliverables

For a country that has global power ambitions, India’s policy of appeasement with Myanmar, which is in constant search of international investment and support for its nascent economy, is intriguing. As the world condemns the Myanmar military for its systematic violation of rights of the Rohingya and other minorities, New Delhi has maintained a studious silence in the hope that such capitulation would reap strategic benefits. In the process, New Delhi seems to have surrendered a key leverage that it possessed vis-à-vis Myanmar.

Some strategic thinkers opine the defence cooperation with Myanmar has allowed New Delhi to develop crucial ties with Myanmar military. Such ties with the defacto rulers of the country were non-existent before and in future, may allow New Delhi to pursue its strategic objectives in that country even in the scenario of a coup dislodging the civilian government headed by Aung San Suu Kyi. New Delhi also believes that when Myanmar’s civilian leadership has made common cause with the military, it makes little sense to flag the Rohingya issue. The future will bear testimony to the success or failure of such a policy.

At present, however, results of the deepening defence ties have remained a mixed bag. The remnants of the northeastern insurgencies continue to find safe haven in that country. Arms and drugs smuggling between the porous Indo-Myanmar border continues to be a major problem. Indian intelligence agencies believe that China could be assisting these Myanmar-based insurgents to destabilize the northeastern states.[10] The fact that India had to launch unilateral surgical strikes in Myanmar against the insurgents- in June 2015[11] and July 2018[12]– underlines that absence of any tangible cooperation between the two armies. India’s capacity building projects for the Myanmar military by providing them with weapons too has not adversely affected the insurgents operating in the northeast. Intelligence reports in the past have suggested that officers within the Myanmar military, for monetary benefits, have not only tipped off the insurgents about impending operations, but have used weapons provided by India in their internal wars, against their own ethnic minorities.[13]

India’s defence diplomacy in Myanmar is indeed a part of its overall scaled-up presence in Southeast Asia. However, it still remains at a nascent level and has certainly not grown to a stage where India can start expecting strategic results. Declarations such as ‘upgrading military cooperation to the next level’ and ‘assisting Myanmar to create a national army’ have little meaning when New Delhi fails to supply OPVs after making promises in 2013. Acquiescing to Myanmar’s out rightly appalling position on the Rohingya may please the military in that country, but would do little to protect India’s interests vis-à-vis the Chinese. There is certainly a need for greater effort and a sustained policy for engagement. New Delhi will have to move beyond rhetoric and implement measures that fulfil its strategic objectives in Myanmar.

End Notes

[1] India-Myanmar Joint Statement issued on the occasion of the State Visit of Prime Minister of India to Myanmar (September 5-7, 2017), Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, 6 September 2017.

[2] “Indian military delegation in Myanmar to boost trust, cooperation”, Financial Express, 23 December 2018, https://www.financialexpress.com/defence/indian-military-delegation-in-myanmar-to-boost-trust-cooperation/1422716/. Accessed on 11 January 2019.

[3] Shakeeb Asrar, “Who is selling weapons to Myanmar?”, Al Jazeera, 16 September 2017, https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/interactive/2017/09/selling-myanmar-military-weapons-170914151902162.html. Accessed on 24 January 2019.

[4] Vijay Sakhuja, “Myanmar: Expanding Naval Ties with India”, IPCS Commentary 3876, 8 April 2013, http://www.ipcs.org/comm_select.php?articleNo=3876. Accessed on 23 January 2019.

[5] Sanjeev Miglani, “India presses on with Myanmar defense supplies in show of support”, Reuters, 21 September 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-myanmar-rohingya-india/india-presses-on-with-myanmar-defense-supplies-in-show-of-support-idUSKCN1BW1UU. Accessed 2 January 2019.

[6] Utpal Parashar, “First Indo-Myanmar joint military exercise begins in Meghalaya”, Hindustan Times, 20 November 2017, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/first-indo-myanmar-joint-military-exercise-begins-in-meghalaya/story-uU6qctYcF5hbTa6UiOliDP.html. Accessed on 3 January 2019.

[7] Prashanth Parameswaran, “What’s Behind the New India-Myanmar Naval Exercise?”, Diplomat, 29 March 2018, https://thediplomat.com/2017/11/new-military-exercise-highlights-india-myanmar-defense-relations/. Accessed on 10 January 2019.

[8] Dipanjan Roy Chaudhury, “India to help modernise Myanmar Army and Navy to broad-base defence partnership”, Economic Times, 12 July 2018, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/india-to-help-modernise-myanmar-army-and-navy-to-broad-base-defence-partnership/articleshow/48111686.cms. Accessed on 10 January 2018.

[9] “India-Myanmar joint training exercise begins in Chandimandir”, Tribune, 14 January 2019, https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/nation/india-myanmar-joint-training-exercise-begins-in-chandimandir/713632.html. Accessed on 30 January 2019.

[10] Samudra Gupta Kashyap, “Chinese agencies helping North East militants in Myanmar”, Indian Express, 10 January 2017, https://indianexpress.com/article/india/chinese-agencies-helping-north-east-militants-in-myanmar-4468384/. Accessed on 24 January 2019.

[11] Subir Bhaumik, “Is Myanmar raid Indian counter-insurgency shift?”, BBC, 10 June 2015, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-33074776. Accessed on 24 January 2019.

[12] Shaurya Karanbir Gurung & Bikash Singh, “Heavy casualties reported in Army’s firefight with Naga insurgents alongside Myanmar border”, Economic Times, 13 July 2018, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/indian-army-carries-out-another-surgical-strike-on-india-myanmar-border/articleshow/60854235.cms. Accessed on 24 January 2019.

[13] Andrew Boncombe, “Swedish-made weapons used to crush Burma’s ethnic rebels traced back to India”, Independent, 14 December 2012, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/swedish-made-weapons-used-to-crush-burma-s-ethnic-rebels-traced-back-to-india-8418166.html. Accessed on 24 January 2019.

(Dr. Bibhu Prasad Routray is the Director of MISS. The analysis is published under Mantraya’s ‘Borderlands’ project. The author can be contacted at <bibhuroutray@gmail.com>. All Mantraya publications are peer-reviewed.)