MANTRAYA POLICY BRIEF#41: 23 AUGUST 2022

SHANTHIE MARIET D’SOUZA

ABSTRACT

Within a year of the Taliban rule in Afghanistan, India’s policy towards the country has shifted from detachment to reluctant engagement. However, the June 2022 decision to reopen its embassy in Kabul has been fueled mostly by hope, multiple overtures from the Taliban, and the changing geopolitics in the region. India has to guard against becoming a tool in the search for legitimacy by the Taliban.

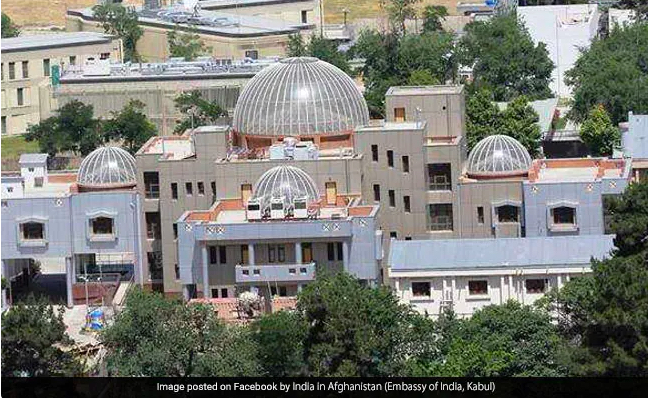

On 12 August 2022, India’s External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar confirmed that a team of diplomats, except the ambassador, have returned to Afghanistan, as part of the country’s focus on maintaining a people-to-people relationship with Afghanistan. The diplomats are part of the small “technical team” who had been deployed to Kabul on 23 June in order to resume India’s diplomatic presence and humanitarian activities in Afghanistan. India’s embassy in Kabul is now fully functional with local Afghan staff. The Taliban have welcomed the ‘return’, assuring both safety and immunity for the diplomats.

India’s move came 10 months after the Indian embassy personnel were compelled to leave as a result of the Taliban entering the capital city on 15 August 2021 — incidentally celebrated as India’s Independence Day — thus abruptly ending a two-decade-long partnership that saw US$3 billion in Indian aid pledges to Afghanistan. The Taliban have claimed that they provided safe passage to the Indian diplomats and citizens during the evacuation. This summer’s resumption of diplomatic activities came about shortly after negotiations between the Taliban and the Indian government. In June first week, a team of officials, headed by an MEA joint secretary visited Kabul and held talks with Taliban officials.

India’s Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) clarified that the decision to reopen its diplomatic mission in Kabul honours the “historical and civilizational relationship with the Afghan people” and will specifically “closely monitor and coordinate the efforts of various stakeholders for the effective delivery of humanitarian assistance.” Clearly, New Delhi had overcome its months of indecision and chosen to be present “where the action is,” rather than continuing to watch from the sidelines.

India’s dramatic policy U-turn has been fueled mostly by hope, multiple overtures from the Taliban, and the changing geopolitics in the region rather than a vision for the long-term stabilization of Afghanistan. Months after the Taliban takeover, New Delhi in various international forums spoke of the need to recognize the threat of terrorism emanating from Afghanistan, push for the establishment of an inclusive government in Kabul, as well as ensure the protection of the rights of Afghan girls, women, and minorities. India also followed up by trying to advance a regional consensus on these issues, involving mostly the Central Asian states.

Neither India’s regional effort nor the absence of international recognition seems to have pressured the Taliban regime to moderate its worldview and policies, however. Notwithstanding token gestures such as donating money to repair the Gurdwara damaged during an attack carried out by the Islamic State’s Khorasan Province (ISKP), the Islamic Emirate of the Taliban remains the replica of the regressive regime that ruled the country in the 1990s. Worse still, the 31 July killing of al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri in Kabul, in an American drone attack, underlined that the Taliban are either unwilling or incapable of severing their ties with terrorist groups.

Rather than pursuing a detached policy or idealistically seeking to transform the Taliban from within, India has apparently chosen to prioritize its presence in Kabul and redevelop political and diplomatic leverage over the one-year-old Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. Such presence, in addition to facilitating India’s efforts to deliver humanitarian assistance, may help it to monitor anti-Indian terrorist activities by groups like the Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) and Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM), which mainly operate out of neighbouring Pakistan. Even more importantly, the Indian mission will be better able to keep tabs on the conduct of China and Pakistan — currently among the greatest benefactors of the Islamic Emirate.

Recent statements by India’s security establishment have underlined that the situation in militancy-affected Kashmir has returned to “near normalcy,” meaning that New Delhi is relatively confident about its ability to manage conflict spillover into Kashmir even notwithstanding the turbulence emanating from nearby Afghanistan. Nevertheless, it is clearly apprehensive of a developing Chinese-Pakistani nexus that could undermine Indian leverage in Kabul while effectively encircling India from the north.

At the same time, deploying only a “technical team” to Kabul remains a safe and easily reversible policy option for India, without any obligation to upgrade it further. It is low-hanging fruit for the Taliban to grab, in return for intensifying their bilateral engagement and recognition of New Delhi as a key player in Afghanistan’s future. New Delhi still underlining that ‘normal’ diplomatic ties with Afghanistan are yet to resume. Jaishankar did not meet Taliban Acting Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi during the SCO summit in Tashkent in July.

To some extent, India’s new posture towards the Taliban displays vulnerability. The conclusion that external factors have compelled India to ‘come around’ is not easy to brush off. That won’t be lost on the Taliban and is certainly not a good tool for complex negotiations in the future. In its search for relevance in Kabul, New Delhi might end up becoming a tool in the Taliban’s elusive quest for legitimacy rather than bringing about any transformational change for the people living in the conflict-ridden country.

(Dr Shanthie Mariet D’Souza is the President and Founder of Mantraya. She currently is a Visiting Fellow in the Research Division Asia at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP). She has conducted field research in various provinces of Afghanistan for more than a decade. A shorter version of this text was first published by the Middle East Institute, Washington D.C. as part of its special briefing on ‘Afghanistan one year on from the Taliban takeover‘. It is republished as part of Mantraya’s ongoing “Fragility, Conflict & Peace Building” project. All Mantraya publications are peer-reviewed.)