MANTRAYA POLICY BRIEF#36: 28 MARCH 2021

BIBHU PRASAD ROUTRAY

Abstract

While extremist attacks claiming lives of security forces in left-wing extremism (LWE) affected states of India aren’t a new and unexpected phenomenon, each such attack underlines the potency of the extremists and provides a setback to the goal of bringing extremism to an end in the coming years. In spite of decades-long counter-LWE operations, vast stretches of multiple states remain under the control of the extremists. Unless operational lapses are addressed and unity of purpose among the central and State governments are established, ending LWE in India may remain a difficult goal to achieve.

Introduction

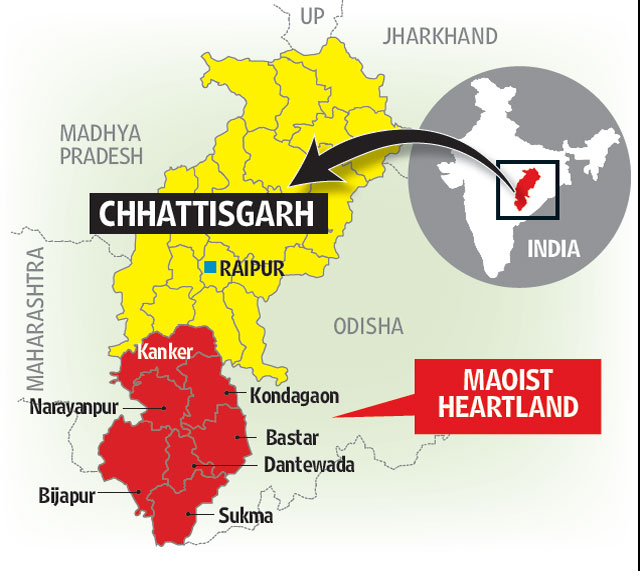

Five security force personnel belonging to the District Reserve Guards (DRG) were killed on 23 March after suspected Left-wing extremists detonated three IEDs under a culvert in Chhattisgarh’s Narayanpur district in the south Bastar region. Chhattisgarh is the worst LWE affected state in the country. This is the biggest attack of 2021 and came exactly a year after an encounter which had claimed the lives of 17 DRG personnel in Sukma district. On the face of it, the incident underlines the persisting threat of the extremists in the region, albeit at a much weaker state. Beneath the surface, however, are the enduring problems with the security force operations as well as the lack of adequate support from the central government.

The Attack

According to available details, about 90 (120, according to some other reports) DRG personnel carried out a two-day operation in Abujhmaad, spread over 4000 square kilometres in Chhattisgarh and neighbouring Maharashtra. Abujhmaad is also believed to be the bastion of the Communist Party of India-Maoist (CPI-Maoist). The operation, part of the Chhattisgarh police’s repeated attempts to breach the sense of safety of the extremist organization, however, did not yield any results. At the end of the operation, DRG personnel started returning to their respective camps. A bus carrying 20 DRG personnel was on its way to the district headquarter took the full impact of the explosions as it moved over a culvert. Three improvised explosive devices (IEDs), assessed to have a combined explosive weight of 40 kilogrammes, exploded tossing the bus onto the dry riverbed below. While three personnel died instantly, two more succumbed to their injuries later. About 14 others were injured, three of them critically. The fact that the explosion wasn’t followed by an ambush leads the police to believe that the IEDs were probably detonated by a couple of extremists in civilian clothes nearby.

Operational Lapses

The standard operating procedure (SOP) prohibits security personnel from using the wireless to communicate their movement plans in advance. The CPI-Maoist, on previous occasions, has been able to eavesdrop into such communication and have been able to target the forces. And yet, the investigation suggests, wireless was used by the DRG to communicate their return route, possibly allowing the extremists precisely organise the explosions.

The second lapse, however, was far more serious. Again, as part of the SOP, IED detection exercise on the route to be taken by the DRG personnel were carried out by a Road Opening Party (ROP). The ROP not only scans the road for possible explosives, but also sanitizes almost 100 metres of either side of the road to rule out ambushes. Surprisingly, even this exercise failed to detect the IEDs, believed to have been planted months in advance. The investigation points to the fact that the wires of the IED were wrapped in a carbon paper and hence, could not be detected. If true, this is a serious limitation and can potentially be exploited by the extremists.

Successes

The IEDs explosion and consequent death of DRG personnel, however, must not undermine the successes of the security forces against the extremists, whose area of operations have continued to shrink. Abujhmaad has been specifically targeted by the security forces with operations, each lasting two to three days. The DRG, consisting of local tribal youths and surrendered extremists, have been in the lead of such operations. Such operations, too short given the vast expanse of the forested region, have resulted in modest gains such as destruction of hideouts and an arms manufacturing unit. Intensification of security force campaigns may have prompted extremists to express their willingness for peace talks with the government on 12 March, provided the operations against them are halted. The offer, however, has been rejected by the Chhattisgarh government, which has asked the extremists to stop violence, give up arms, and abide by the Indian constitution. Maoists, on the other hand, have rejected the mediation efforts of the newly formed Concerned Citizens’ Committee of Chhattisgarh, by terming its convenor, Shubhranshu Choudhary, a former BBC journalist, a ‘corporate agent’. With the peace process heading nowhere, a force centric approach dominates the official strategy to deal with LWE. According to official data, in the last three years (2018-2020), 216 extremists have been killed and another 966 cadres have surrendered in the state. The state security establishment senses an opportunity to decimate the extremists by its current approach.

Shortcomings and Challenges

This, however, is easier said than done. According to private assessments, ‘nearly 15,000 square kilometres in south Bastar region are not under government control. In another 10,000 square kilometre, the control is shared by the state and the extremists’. In this context, the faux pas that may have led to the killing of the DRG personnel on 23 March, is bound to occur periodically in various forms. The state police establishment continues to suffer from a range of operational and technical deficiencies. The state police officials have indicated that better network of human and technical intelligence would have averted incident. Over the years, the state police have tried expanding its human intelligence (Humint) in the interior areas. The net objective of improving the flow and quality of Humint, however, has been challenged by the extremists with a policy of vengeful killing of suspected police informers. In Bijapur district alone, where the Maoists allege that the police is trying to expand its informer network among the poor tribals, 25 such people have been killed, in the second half of 2020.

Centre-State Divide

For past several years, Chhattisgarh remains the worst LWE-affected state in the country. Given the enormous challenge it faces, it is necessary for the state to receive overwhelming support from the central government, both in terms of security force deployment as well as development initiatives. Available indications suggest that such support may not be forthcoming from the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) to the state, which is ruled by the opposition Congress Party. For instance, in 2018, seven battalions of Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) were sanctioned for Bastar region. They have not been dispatched to the state till date. Worse still, 10 CRPF battalions have been removed from the state and deployed in Kashmir since 2019, leaving Chhattisgarh to manage its counter-LWE operations with 33 battalions of CRPF personnel.

Other sanctioned and not implemented projects for the state include 1028 mobile towers for improving telecommunications in LWE-affected districts. Additionally, in November 2020, the state Chief Minister Bhupesh Baghel wrote to the Home Ministry seeking assistance for creating employment opportunities for youths in LWE-affected areas, providing electricity to remote areas, installation of solar power plants, establishing processing units and cold chains, and providing additional financial grants to the ‘aspirational districts’ of the state identified by the Niti Aayog. Sources in the Chhattisgarh government indicate that none of these requests have received positive response from the central government.

Way Ahead

Loss of the lives of security forces in a conflict theatre is a tragic, but unavoidable outcome. In the case of Chhattisgarh, where extremists continue to control a huge landmass, even strict adherence to SOPs, may not completely prevent casualties among the forces. There can be no alternative to the resolution of conflict through a progressive control over extremism. Each successful strike by the extremists provides a serious setback to that staggered objective. As a result, ending LWE in the country seems difficult to achieve, even with the rather extended time frame of 2025 set by the MHA. All LWE affected states of the country, especially the contiguous ones, need better coordination with one another. All affected states, in turn, must also be supported by New Delhi in terms of deployment of adequate number of security forces, and also, by the faster implementation of identified development schemes. There is unanimity among the states and the Central government that LWE needs a multipronged approach. It is time that this identified policy—combining development, security force operations, justice administration and strategic communication—is implemented without political and other considerations.

(Dr. Bibhu Prasad Routray is Director of Mantraya. This policy brief is published as part of Mantraya’s ongoing “Fragility, Conflict, and Peace Building” and “Mapping Terror and Insurgent Network” projects. All Mantraya publications are peer reviewed.)