MANTRAYA ANALYSIS#67: 04 JULY 2023

BIBHU PRASAD ROUTRAY

Abstract

Opium production in Afghanistan has significantly declined. But it has surged in Myanmar. The military, which is in power following the coup in February 2021, is neither willing nor capable of launching a war on opium cultivation and the rapidly growing production of synthetic drugs. On the contrary, evidence has emerged linking the military’s top brass with the drug syndicates and some of the ethnic armed organisations involved in the production and smuggling of drugs. As wide-scale poverty and a plummeting economy create a conducive environment for drug production, the regional countries need to worry about being flooded with contraband in the near and medium term.

Introduction

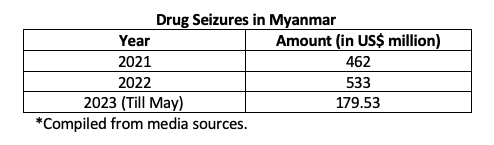

On 26 June, Myanmar authorities came with a rare admission after setting fire to seized narcotics—heroin, cannabis, methamphetamines, and opium—worth $446 million. Soe Htut, Chief of Myanmar’s Central Committee for Drug Abuse Control said that the government’s efforts to crush the narco-trade were having no impact.[1] The military-formed government is trying to appear sincere in its approach and is perhaps soliciting international cooperation, which has more or less vanished following the coup in April 2021. But the fact remains that far from being sincere about controlling poppy cultivation and the narco trade, the coup it orchestrated in February 2021 has reversed the gains made in the last decade. Worse still, in a plummeting economy affected by wide-ranging sanctions by the Western countries and flight of investors from the country, the military is aligned, directly and indirectly, with the drug cartels to profiteer from the multibillion-dollar trade.

Narco-Economy

Myanmar, part of the infamous golden triangle along with Thailand and Lao PDR, is the world’s second-largest producer of opium, after Afghanistan. Myanmar’s opiate economy’s estimated value ranges between US$ 660 million to 2.0 billion, according to U.N. estimates. The country produces most of the region’s methamphetamine. More than 23 tonnes of these synthetic pills were seized in Myanmar in 2022. The country also is the main source for the drug for most of East and Southeast Asia.

In 2022, according to the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), which started tracking Myanmar’s poppy crops for the first time in 2002, the country’s farmers grew an estimated 40,100 hectares of poppy. This is an increase of 33 percent from 2021.[2] In 2013, poppy farming had peaked reaching 57,814 hectares. It dipped to under 30,000 hectares in 2020 as a result of sustained government initiatives. However, the military coup of February 2021 dislodged the civilian government and pushed the country to instability and poverty appears to have created the conditions for the revival of a conducive atmosphere for poppy cultivation.

Sustaining Opiate economy

Two factors could be responsible for the reversal of a decade’s trend as far as the production of opium and synthetic drugs is concerned: (i) Rising prices for the contraband crop and (ii) an economic nosedive that’s wiping out jobs and pushing farmers into impoverishment. According to the World Bank, says Myanmar’s economy contracted by 18 percent in 2021, and poverty has doubled since 2020, leaving 40 percent of the population below the national poverty line. The UNODC’s representative for Southeast Asia and the Pacific, Jeremy Douglas, has said that following job losses and drying opportunities for finding employment ‘in Yangon or Mandalay or other parts of the country, and people have left and returned back to rural areas, returned to farming’ poppy.

The UNODC also says that the yield from the poppy fields too has increased to an average of 19.8 kilograms of opium per hectare of poppy, the highest-ever measured estimate in Myanmar. According to the UNDC, in this season, farmers earned twice as much selling opium in 2022 as they did the previous year. Prices for a kilogram of opium increased 70 percent from $166 to $281.[3] An additional reason for the bumper crop is the investment made by the armed insurgent groups, who reportedly provided the farmers with seeds, fertilizer and in some cases irrigation equipment. The harvests were bought by these groups and trafficked out of the country, after being processed into heroin.

Myanmar’s heroin, although only a fraction of what is produced in Afghanistan, is still considered the best in the world. Combined with the Taliban’s effort to contain poppy cultivation in Afghanistan, which reportedly has reduced the area under cultivation by as much as 80 percent, there could be a huge surge in demand for the Myanmarese crop from regions such as Europe and the US, which so far consumed mostly the supply from Afghanistan.

Shan State and Beyond

The Shan State, bordering China, remains the centre of Myanmar’s opium activities, accounting for 84 percent of opium poppy cultivation, with the remainder located mainly in Kachin State and small areas in Kayah and Chin states. The powerful Ethnic Armed Organisation (EAO) with 25000 to 30000 fighters, the United Wa State Army claims to be fighting for autonomy for Myanmar’s ethnic minority Wa. It operates from a reclusive virtually autonomous area, called Special Region 2 (SR2), within the Northern Shan state as well as a semi-contiguous region along the Thai border in Southern Shan State. While the UWSA has a long history of participating in and benefiting from poppy cultivation and drug trade, the UNODC has found evidence that the USWA in 2022 promoted opium cultivation, just outside SR2. SR2 runs along Myanmar’s border with China, the main market for the country’s opium and heroin.

Incidentally, in 1997, the United Wa State Party (UWSP), of which the UWSA is the military wing, officially proclaimed that Wa State would be drug-free by the end of 2005. With the help of the United Nations and the Chinese government, many opium farmers in Wa State shifted to the production of rubber and tea. Periodically, the UWSP arrests drug smugglers, seizes Methamphetamines, and burns banned drugs. However, these measures could only be token and face-saving in the face of wide accusations of being involved in the drug trade.

The UWSP has not sided with the pro-democracy forces following the February 2021 coup. In January this year, it participated along with another insurgent organisation, the Shan State Progress Party (SSPP) in negotiations with the military with regard to holding elections in areas under their control.[4] An SSPP spokesperson told the media that the military had asked them “to let them hold free and fair elections in our area. For us, we will not oppose their election.” This is in contrast to the position of the parallel National Unity Government (NUG) and some of the EAOS aligned with it who oppose the plan to hold elections.

However, while the UWSA could be the biggest player in running the drug trade, many other EAOs, both fighting military or are cahoots with it, too have indulged in the same to generate money to run their insurgencies. Some participate in the entire trade, starting from farming to exporting drugs. Other involvement can be specific ranging from providing security to a processing unit to transporting the contraband.

In 2022, following the arrest of four men in the US trying to broker the drugs-for-weapons deal for the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA), the Shan State Army-South (SSA-South), and the UWSA, with Japan’s yakuza crime syndicate. The brokers were trying to seal a deal for surface-to-air missiles which will be paid for with a mix of cash and drugs. The KNLA denied the charge.[5] The KNLA is opposed to the military and has been fighting alongside the NUG.

The Military and Opiate Economy

Myanmar’s military government blames some of the EAOs for the state of affairs and says that they do not cooperate in the country’s peace process as it will disrupt the gains they made from the drug trade. However, apart from playing an indirect role in propping up the poppy cultivation, the junta has been accused by analysts of not being serious about ending the lucrative trade. For instance, an independent analyst was quoted in a news report saying, The army is “actually the ultimate protection cartel of the trade and have been for many years.”[6]

This happens at two levels. Firstly, its efforts to eradicate poppy cultivation remain insincere. Although the state-run Central Committee for Drug Abuse Control claims thousands of hectares of poppy fields are eradicated each year, such efforts have registered a sharp decline, from 4633 hectares in 2021 to 1403 in 2022. Moreover, the UNODC data do not demonstrate the impact of such efforts on how much poppy is actually grown each year. The accuracy of official data also remains questionable as the government often counts poppy fields as ‘cleared’ after the plants had already been harvested for the season. In the absence of official efforts, some of the EAOs have taken drug enforcement into their hands, sometimes using harsh methods.[7]

And secondly, the military’s top brass themselves could be actively involved in the drug trade and transnational organised crime. A rather clear evidence emerged in September 2022 when during a raid in Bangkok, Myanmarese businessman Tun Min Latt and three other Thai nationals including a senator’s son were arrested[8] and over 200 million baht (US$5.4 million) worth of assets were confiscated from them.[9] Also recovered during the raid were title deeds of assets belonging to the son and daughter of Myanmar’s military chief Min Aung Hlaing. Thai police have charge-sheeted Tun Min Latt with money laundering, drug trafficking, and transnational organized crime. Tun Min Latt, who has interests in hotels, energy, and mining, is a known close associate of Min Aung Hlaing and has helped the military with monetary donations and arms purchases.[10]

Additionally, some of the militia forces directly under the military junta, such as the Pyu Saw Htee, are allegedly producing drugs in the Shan state to fund food and salaries for their fighters.[11] The Kokang Border Guard Force, which operates under military protection, produces opium in the special administrative zone it operates in the Eastern Shan state.[12]

Ominous Signs

Poppy cultivation is mostly about poverty and economics and therefore, the destruction of poppy fields alone can only be an ad-hoc measure. These methods are utterly futile given the scourge of synthetic drugs like methamphetamine which primarily depends upon chemical supplies from abroad. Similarly, Opium is converted into heroin using Acetic anhydride supplies from India and China, according to the UNODC. Without a strong economy and viable alternatives to growing poppies, farmers will find growing poppies an attractive option to support their families. Without the state’s writ enforced upon the territory, synthetic drug processing units will continue to thrive. Catering to the demands in Southeast and East Asia, Myanmar could be poised to fill up the vacuum created by the dip in production in Afghanistan.

There are ominous for Myanmar’s neighbours such as India, China, and Thailand who have chosen to deal with the military after the coup, disregarding the appeals by the pro-democracy forces. One of the reasons for their decision is to work through the military in power to address their concern regarding the drug trade. Facts on the ground point to the contrary. The military is neither capable of nor willing to initiate an honest and serious war on drugs in Myanmar. This would invariably result in transnational organised crime groups using the regional countries as final destinations and transit routes for contraband smuggling.

END NOTES

[1] “Myanmar junta says failing to halt surge in drug trafficking”, Bangkok Post, 26 June 2023, https://www.bangkokpost.com/world/2599658/myanmar-junta-says-failing-to-halt-surge-in-drug-trafficking.

[2] Zsombor Peter, “Myanmar’s Opium Production Said to be Surging After Years of Decline”, Voice of America, 26 January 2023, https://www.voanews.com/a/myanmar-s-opium-production-said-to-be-surging-after-years-of-decline/6934727.html.

[3] Cara Tabachnick, “Opium production rises in 33% Myanmar, the first season after military coup, U.N. report says”, CBS News, 28 January 2023, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/opium-production-rises-myanmar-first-season-after-military-coup-u-n-report/.

[4] “Myanmar’s military holds election talks with armed ethnic groups”, Al Jazeera, 7 January 2023, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/1/7/myanmars-military-hold-election-talks-with-armed-ethic-groups.

[5] Zsombor Peter, “Myanmar Rebel Group Denies Role in Alleged Drugs-for-Weapons Scheme”, Voice of America, 29 April 2022, https://www.voanews.com/a/myanmar-rebel-group-denies-role-in-drugs-for-weapons-claims/6550168.html.

[6] “Myanmar authorities burn $446m in illegal drugs”, Al Jazeera, 26 June 2023, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/6/26/myanmar-authorities-burn-446m-in-illegal-drugs.

[7] “Resistance armies fight post-coup drug scourge with harsh methods”, Frontier Myanmar, 14 March 2023, https://www.frontiermyanmar.net/en/resistance-armies-fight-post-coup-drug-scourge-with-harsh-methods/.

[8] Panu Wongcha-um and Poppy Mcpherson, “Thailand arrests Myanmar military-linked businessman suspected of drug trafficking”, Reuters, 21 September 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/thailand-arrests-myanmar-military-linked-businessman-suspected-drug-trafficking-2022-09-21/.

[9] “Myanmar Junta Crony Pleads Not Guilty to Drug, Financial Crimes in Thailand”, Irrawaddy, 25 January 2023, https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/junta-crony/myanmar-junta-crony-pleads-not-guilty-to-drug-financial-crimes-in-thailand.html.

[10] “Myanmar junta chief family assets found in Thai drug raid: Report”, CNBC, 11 January 2023, https://www.cnbctv18.com/world/myanmar-junta-chief-family-assets-found-in-thai-drug-raid-report-15641391.htm.

[11] “Drug trade thrives in lawless post-coup Myanmar”, Radio Free Asia, 27 June 2023, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/myanmar/drugs-06262023174441.html.

[12] The Myanmar Army’s Criminal Alliance, United States Institute of Peace, 7 March 2022, https://www.usip.org/publications/2022/03/myanmar-armys-criminal-alliance.

(Dr. Bibhu Prasad Routray is the Director of MISS. This analysis has been published as part of Mantraya’s ongoing “Fragility, Conflict, and Peace Building” project. All Mantraya publications are peer-reviewed.)