MANTRAYA ANALYSIS#25: 15 MAY 2018

BIBHU PRASAD ROUTRAY

Abstract

Rising demand has transformed Myanmar into the prime producer of synthetic drugs. It’s a US$ 4 billion economy. Production of and trade in narcotics in Myanmar registers continuous growth in spite of a decrease in area of production of poppy and growing success by the police personnel in seizing the contraband. A new drug control policy notwithstanding, controlling the spiraling trade will be difficult unless a cooperative mechanism is established among the regional countries.

(Drug Seizure in Myanmar in October 2017, Source: Borneo Bulletin)

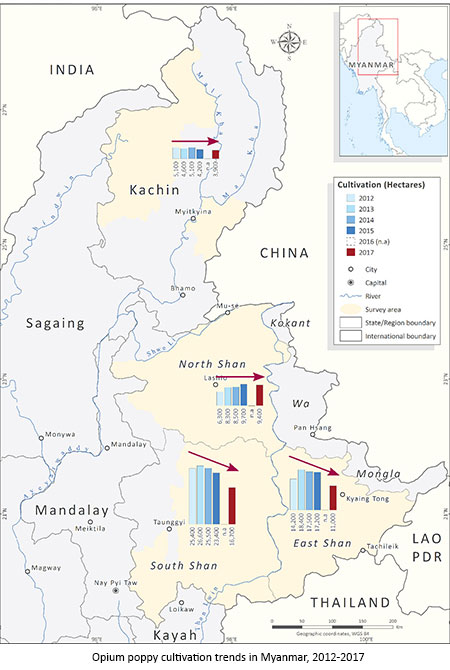

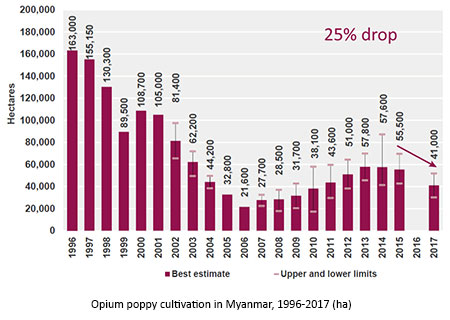

The total area of opium poppy cultivation in Myanmar decreased in 2017 to 41,000 hectares, from the 55,500 recorded in 2015. This 25 percent decrease was most significant in eastern and southern Shan state (drops of 37 and 29 percent, respectively). Northern Shan and Kachin states, however, reported less reductions (3 and 7 percent, respectively). Nevertheless, reductions in cultivation have been somewhat offset by a greater yield per hectare. More significantly, the arrival of synthetic drugs makes production area a less viable metric. As a consequence, the Golden Triangle is set to retain its notoriety till a regional cooperative mechanism confronts the challenge.

History

Credit for introducing opium to Burma indeed goes to the British, who in 1852 started bringing in large quantities from India. This imported opium was sold through a government-controlled opium monopoly, but over time, the northeast, especially the Shan state, started growing opium and smuggling it. This led to a significant increase in the number of Burmese opium addicts, so many that by 1878, the alarmed British made an ineffectual effort through the Opium Act to restrict the selling of opium to only registered Chinese and Indians. Burmese were strictly banned from smoking opium.

By 1886, the British had acquired the Shan state, yet this had no impact on the thriving opium production and smuggling. The trend continued even after Burma achieved its independence in 1948. By that time, in addition to the Shan state, poppy was being grown (and continues) in the Shan, Kachin, Karenni, and Chin states. Even though the Ne Win government outlawed opium in 1962, impact on production was minimal. In fact, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), involved in Vietnam, was allegedly airlifting opium cargos for its various allies. In 1984, the US State Department concluded that its crop substitution programme, not just in Golden Triangle but in all other opium producing regions, was producing poor results and that opium needed to be fought through plant eradication and criminal enforcement. This led to supply of herbicides to Burma, but under the SLORC regime of the Burmese military (1988-1997), opium production continued to increase. By 1995, the Golden Triangle region was producing 2,500 tons of opium annually and smuggling them through trafficking routes from Burma through Laos, to southern China, Cambodia and Vietnam.

Changing Regional Drug Market and its Scale

(Source: UNODC)

Fast forward to the present. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) data for 2017 indicating a decrease in Myanmar poppy growing areas in reality gives no reason to celebrate. The decline in opium cultivation has occurred, UNODC admits, against the backdrop of ‘a changing regional drug market’. While opium and heroin prices have fallen in recent years, most East and Southeast Asian countries report a shift to synthetic drugs and especially Amphetamine-Type Stimulants (ATS) in various forms. It appears much of the reduction in poppy growing areas has taken place not so much due to official policies and enforcement but due to the fact that poppy-based drugs are now less profitable than synthetic. In the Golden Triangle region, it is possible to clearly distinguish between what used to be an age of opiates and what currently is the time for ATS.

(Source: UNODC)

Synthetic drugs indeed are highly attractive to organized crime and aspiring criminal entrepreneurs. Compared to heroin, the category is more potent, has higher profit margins (manufactured for roughly US $0.25 and selling for over US $2 a pill). They are compact and hence have simpler logistics. Unlike opiates or cannabis, ATS can be manufactured anywhere and are not reliant on natural plant sources.

Low-purity amphetamine tablets, a combination of methamphetamine and caffeine, are sold in many ASEAN countries as ‘Yaba’, a Thai word which translates to ‘crazy medicine’. The Yaba market is a low-profit, high-volume sale opportunity for criminal groups, which produce pills in the tens to hundreds of millions. The drug tourist destination that Southeast Asia has become needs an increasing supply of drugs and synthetic drugs to meet demand. In 2008, it was estimated that roughly half of the world’s 15-16 million meth users were located in East and Southeast Asia. The pure and stronger variant of methamphetamine – known as crystal methamphetamine or ‘ice’ – is exported to countries such as Australia and China. Sales volumes in those markets are relatively low, but demand is on the rise.

Although a particular year is difficult to be identified, the shift coincided with the early 2000s rise of efforts by UNODC and state governments to counter drugs. The number of meth labs busted in East and Southeast Asia was nearly 10 times higher in 2009 than in 2005. Pill seizures in China, Laos, Myanmar, and Thailand jumped from 32 million in 2008 to 133 million in 2010. In 2011, UNODC reported that the Mekong River, linking Laos, Cambodia, and Thailand, was swiftly becoming one of the key ATS trafficking points, disseminating the new product from the Golden Triangle. The shift has continued with each passing year, in many ways making the opium-based drugs a ‘golden oldie’ in the war on drugs.

According to UNODC, since 2015, East and South-East Asia have become the leading sub-regions for methamphetamine seizures worldwide. How meth demand and corresponding production have increased can be inferred from the seizure data in Myanmar, although seizure also denotes strengthening of the country’s law enforcing capacities. In 2016, Myanmar police confiscated 98 million meth pills, nearly doubling their achievement of 2015 in which 50 million pills had been recovered. In addition to the tablets, 759 kilograms of heroin, 945 kilograms of opium, and 2,464 kilograms of ‘ice’ were seized in 2016. Corresponding drug prosecutions, consisting mostly of low-level smugglers, numbered 13,500 compared to some 8,800 in 2015. Still, such arrests and seizures have done little to stem the tide of production of synthetic drugs. In January 2018, Myanmar police seized 30 million meth pills along with more than two tonnes of “ice” and heroin from a house in Shan state’s Kutkai township, arguably the biggest seizure in terms of value and quantity in the country’s history. In addition to the meth pills, 502 kilograms of heroin and 1,750 kilograms of crystal methamphetamine or ice also were seized. The total seizure was worth US$ 54 million, amounting to one-fifth of the total narcotics seized in the country in all of 2017.

At a conservative estimate of US$2+ street price for each meth pill, the seizures alone were worth US$ 200 million. With an optimistic calculation of one-fourth of the pills being seized by the police, the methamphetamine economy in Myanmar in 2016 was worth close to US$ 800 million. If the expensive ‘ice’ pills and the opium-based drugs are added, the net narco-economy of Myanmar was worth US$ 2 billion (2016). Calculating on the basis of a near-100 percent increase in the levels of all drugs, and a slight rise in the street price of the Meth pill in East and Southeast Asia, the narco-economy of Myanmar in 2017 can be conservatively estimated to be at least US$ 4 billion. The amount is small compared to the Afghan opium trade, worth US$ 60 billion, but in terms of impact on the lives and economies of the host state and the region, the impact could be devastating.

The Players

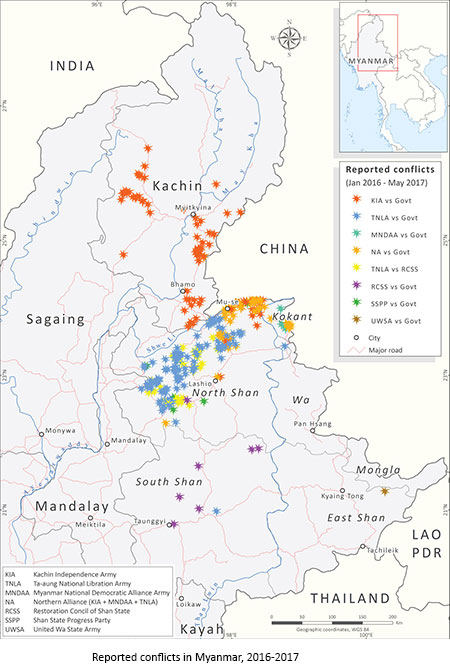

(Source: UNODC)

During the age of the opiates, the Shan warlord, Khun Sa, exemplified the nexus between the state and the opium production and smuggling. A former Kuomintang Chinese Nationalist Army soldier, Khun Sa, at the height of his power in the 1980s, was believed to have controlled at least 70 percent of the heroin trade in the Golden Triangle region. In 1996, he surrendered to authorities and retired quietly to Yangon, amid suspicion that this agreement between the ruling Junta and Khun Sa included a deal allowing him to retain control of his opium trade but in exchange ending his 30-year-old revolutionary war against the government. By then, though, the northern region of the country was mushrooming with drug lords and their militias.

As the Junta was attempting to seek ceasefires with ethic insurgencies in the 1990s, those drug lords who doubled as ethnic armed resistance leaders were allowed to begin to produce drugs on a grander commercial scale. In 2016, a member of Parliament of the Myanmar’s upper house, Khun Than Pe, representing the Shan State, observed, ‘It was in the 1990s that [the drug problem] spread across both urban and rural areas. It is fair to say that [the problem] was born with “peace”.’

Interestingly, agencies like the UNODC, has historically been reluctant to point at a nexus between rising narcotics’ production and the role of the government. The reluctance is understandable, for it would jeopardise its ability to work in the country. Therefore, much of the issues UNODC highlights pertains to direct linkages between conflict and opium in Myanmar. These are valid reasons, but don’t provide a comprehensive picture of narco economy in Myanmar. Areas under domination of ethnic insurgencies do produce more opium than the areas which are insurgency-free. As a result, the Shan and Kachin states, where insurgencies have defied official attempts to secure participation in the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA), continue to cultivate and produce opium at levels similar to 2015. At another level, since these areas suffer from acute governance deficit and poverty, a link between poverty and drug production too is undeniable. The opium economy in Myanmar thus supports a large population. In Shan State, for instance, where production is centred, approximately 600,000 people are directly supported by opium farming. Over time, the problem has spread to regions where opium is not cultivated. For instance, though Arakan state does not grow poppy, drugs are openly available there, even in the Beetle nut shops.

Synthetic drug production builds on the expertise of the cartels that dealt with the opiates. While the trade has disrupted the established farmer-traffickers-cartel links and taken the farmers off the scene, it has made the problem and its associated networks more complex by bringing in international as well as smaller local players. The US$ 4 billion annual narco economy in the country generates enough stakeholders to keep the trade rolling. Organised crime groups in Laos and Myanmar have become significant players in the production of ATS.

A New Approach

In the past, the Myanmar government has focused primarily on supply reduction, including reduction of opium poppy cultivation. The Home Minister admitted that this single focus did not achieve much. Though the government formed dedicated drug squads in the police force at the division and state level, they were understaffed and under-equipped to arrest take on the resources of the drug lords. Government officers repeatedly leaked information to the drug kingpins, resulting in raids that arrested only the users and small-time street dealers.

In February 2018, after nearly three years of consultations, the Myanmar government and UNODC announced a new National Drug Control policy. The document is the product of attempts to rebalance the approach to the challenges that drugs pose to the country, focusing on its unique needs. The policy, adopting the framework provided by the 2016 UN General Assembly Special Session on the World Drug Problem (UNGASS), signals a significant shift towards an evidence-based and more people- and health-focused approach, while advocating practical strategies to reduce the negative effects of drug production, trafficking, and use. A product of wide-scale consultation process, the new policy seeks to focus on five policy areas: supply reduction and alternative development; demand and harm reduction; international cooperation; research and analysis; and compliance with human rights. Significantly, it is the first time the government of Myanmar has formally adopted a harm reduction approach to drug use.

Conclusion

Nevertheless, a drug-free Myanmar cannot be achieved without success in the peace process. As long as significant parts of Shan and Kachin states remain unstable and basically autonomous from the rest of the country and region, the environment will remain a safe haven for those who run the drug trade. At the same time, endemic official corruption and drug syndicates’ ability to bounce back from raids with ramped-up production will continue to boost the synthetic drugs market. Lastly, rising demand, the huge profit margin, and lack of a concerted and coordinated approach by regional countries will remain some of the critical challenges for problem to be addressed effectively. In the past, Myanmar has benefited from joint anti-drug operations with China and Thailand. Clearly, that has not been enough. Regional cooperation is needed to fight the problem.

References

Booth, Martin. Opium: A History. (London: Simon & Schuster, Ltd., 1996).

Douglas, Jeremy. “In Asia, the unintended consequences of fentanyl”, Globe and Mail, 23 February 2018, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/in-asia-the-unintended-consequences-of-fentanyl/article38064851/. Accessed 29 April 2018.

Francis Wade, ‘The shady players in Myanmar’s drugs trade’, al Jazeera, 26 September 2012, https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2012/09/201292295654887542.html. Accessed 12 May 2018.

“Myanmar makes record drug bust with 30 million meth pills”, The Straits Times, 18 January 2018, https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/myanmar-makes-record-drug-bust-with-30-million-meth-pills. Accessed 10 May 2018.

Nan Lwin Hnin Pwint, ‘Lawmakers Blame Burma’s Drug Problem on Warlord-Govt Nexus’, Irrawaddy, 4 August 2016, https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/lawmakers-blame-burmas-drug-problem-on-warlord-govt-nexus.html. Accessed 1 May 2018.

‘Record year for Myanmar meth pill seizures’, Myanmar Times, 2 February 2017, https://www.mmtimes.com/national-news/24791-record-year-for-myanmar-meth-pill-seizures.html. Accessed 10 May 2018.

Turow, Eve. “The High Lands: Exploring Drug Tourism Across Southeast Asia”, The Atlantic, 7 March 2012, https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2012/03/the-high-lands-exploring-drug-tourism-across-southeast-asia/253705/. Accessed 30 April 2018.

UNODC, Myanmar opium cultivation declines sharply, except in some conflict areas: UN report, 6 December 2017, https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/frontpage/2017/December/myanmar-opium-cultivation-declines-sharply–except-in-some-conflict-areas_-un-report.html. Accessed 24 April 2018.

UNODC, New national drug policy announced for Myanmar, 20 February 2018, https://www.unodc.org/southeastasiaandpacific/en/myanmar/2018/02/new-national-drug-control-policy/story.html. Accessed 23 April 2018.

(Dr. Bibhu Prasad Routray is the Director of MISS. This analysis is published as part of Mantraya’s ‘Borderlands’, ‘Organized Crime and Illicit Trafficking’, and ‘Mapping Terror and Insurgent Networks’ projects. The author can be contacted at <bibhuroutray@gmail.com>. All Mantraya publications are peer-reviewed.)