MANTRAYA ANALYSIS#10: 28 SEPTEMBER 2016

NIVEDITA JAYARAM

Abstract

Afghanistan has been presented a tremendous opportunity for economic development through the One Belt, One Road (OBOR) initiative, which will help it overcome bottlenecks to economic development through investment in transportation, energy and telecommunications infrastructure. Afghanistan’s advantageous geographical position and abundant natural resources, if utilized appropriately, could make the country an important player in intraregional trade and energy networks, both as a supplier and a transit hub. However, in the light of the deteriorating security situation, and China’s consequent aloofness in establishing a concrete role for Afghanistan, economic benefits from the project will depend largely on the ability of its government to create a positive environment for trade and investments.

Introduction

Afghanistan’s unique geographical position makes it an important link between South and Central Asia, as well as East and West Asia. It is also richly endowed with natural resources that could pave the way for economic growth. However, the country has not been able to leverage these advantages to facilitate economic development due to a long history of war and political instability. The Afghan economy is characterized by a low GDP growth of 1.5 percent, high levels of inflation, and unemployment. It has a negative trade balance of USD 5.65 billion, due to high dependence on imports amounting to USD 6.42 billion, while exports remain low at USD 770 million. More than one-third of Afghanistan’s population lives below the poverty line, and country’s main source of income continues to be international funding, which financed 90 percent of its development budget in 2015.

The National Unity government, following its formation after the parliamentary elections of 2014, expressed the intention of reducing foreign dependency, and rebuilding Afghanistan’s economy on a more sustainable model. This declaration followed China’s release of its plans for the One Belt, One Road (OBOR) project in 2013. The OBOR commits USD 890 billion for 900 projects in transport, energy and telecommunications infrastructure in 60 countries. It will create economic integration networks for trade and transit across Eurasia, covering two-thirds of the world’s population, 55 percent of global GDP and 75 percent of global energy reserves. This prompted Thomas Zimmerman to note that, ‘the OBOR has the potential to integrate Afghanistan into the regional economy, in ways that the US has sought to do for years”.

However, Afghanistan’s integration into the OBOR and achievement of the potential benefits from such integration are complex matters. While Sino-Afghan relations have considerably improved in the past years, with China emerging as the largest investor in the country, it has remained aloof with respect to Afghanistan’s internal political and security challenges. This is reflected in its reluctance to announce the manner in which Afghanistan is to be linked to the OBOR, as well as concrete investments in Afghanistan under the project. Whether the OBOR will transform Afghanistan’s economic future is dependent on the ability of the country to create an environment that enables its positive participation in intraregional trade and transit.

Opportunities from the OBOR

Afghanistan has the potential to play a major role in intraregional trade and transit. Being a resource rich nation, it could benefit from access to regional and international markets. Its strategic location as the ‘Heart of Asia’ could make it an important transit hub in the region. The nascent nature of Afghanistan’s road and rail networks has prevented it from taking advantage of intraregional and international trade. An example of this shortcoming is reflected in the large trade costs of exports from Afghanistan to Central and West Asia. It takes 89 days for exports from Afghanistan to reach these countries. Lack of connectivity has also acted as a barrier to fulfilling Afghanistan’s aspiration of being the regional ‘roundabout’ for trade and transit. For instance, it has been noted that if 20 percent of South Asia’s western trade were transported through roads, goods worth USD 100 billion dollars would pass through Afghanistan. Afghanistan’s improved connectivity with the regional economy through trade and transit is estimated to bring earnings worth USD 606 million to the country. Improved connectivity is also important in reducing the costs of imports, as well as inflation. This is especially relevant for Afghanistan where 90 percent of commercial products come from abroad.

OBOR envisioned infrastructure investment would address the major bottleneck of infrastructure financing gap in the country. OBOR countries would also enjoy favorable lending terms from the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the Silk Road Fund. The OBOR project entails a shift of Chinese labour intensive manufacturing industries to less developed OBOR member countries. China’s manufacturing industries are large; presently employing 125 million people, of whom 85 million are engaged in labour intensive industries. The upgradation of Chinese manufacturing industry and relocation of factories in countries along the OBOR belt provides the opportunity for industrialization in less developed economies. China’s industrial overcapacity in cement, steel, photovoltaic cells etc. can be used to address Afghanistan’s shortage of capital inputs, while infrastructure development would create local employment leading to higher incomes in the country. Afghanistan would also benefit from access to Chinese markets, with a large demand for raw materials.

Afghanistan’s medium and long-term economic development would depend on its agriculture, mineral and oil and gas sectors. Large proportions of the country’s population remain dependent on agriculture, and the development of this sector is essential for addressing poverty. Improved connectivity is imperative to the integration of the country’s agriculture sector into regional and global value chains. Afghanistan is richly endowed with untapped natural resources that could make it a potential supplier of energy. Investments in mineral exploitation would allow the Afghan economy to sustain itself by enhancing revenue, and reducing foreign dependency. Afghanistan’s mineral reserves are valued at USD 3 trillion. Western Afghanistan has a large wind energy and hydro-power potential. However, in 2015, the government only earned USD 30 million from resources. Under the OBOR, investments in Afghanistan’s oil and gas sectors will in turn be supported by access to international markets of large energy importing countries such as India and China. Further, Afghanistan could benefit not only as a supplier, but also as an energy transit hub between Central Asian countries and energy markets in China and South Asia. The seasonal energy deficit in Central and South Asian countries could be resolved by transmission of surpluses through Afghanistan. Presently, only 20 percent of Afghanistan’s population has access to electricity. The irregularity of electricity supplies from Central Asia could be made more stable through integration into the OBOR’s electricity transmission grids.

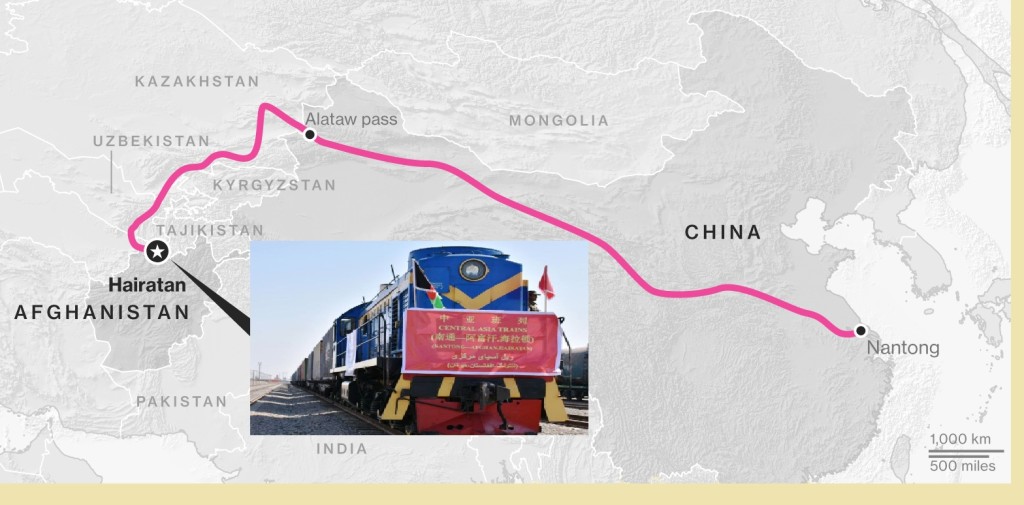

Freight Train from Jiangsu to Hairatan

There are a few positive steps that signal China’s commitment to its promises. The first freight train from Jiangsu in China to Hairatan in Afghanistan was inaugurated in August 2016. While this is a part of Chinese intentions to increase markets for Chinese goods, rail connectivity has benefits for Afghanistan. The country’s existing road network is congested and lacks proper maintenance, and can be supplemented with improved rail connectivity. Connectivity with China will also reduce price of imports by 30 percent, which will in turn reduce inflation. Afghanistan will gain access to Chinese markets and regional markets, while allowing it to do so without transiting through Pakistan. China has also emerged as the largest investor in Afghanistan. One, the USD 3.5 billion investment by Chinese Metallurgical Group Corporation (MCC) in the MesAynek copper mines in 2007. Two, an oil extraction project in Amu Darya worth USD 400 million investment by the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC). Improved infrastructure around these projects, as well as better connectivity between mining centers and regional and international markets have been promised.

Challenges to the OBOR

China has stepped up its engagement with Afghanistan since 2012 as part of its new diplomatic initiative to strengthen relations with its neighbours. To this end, it has enhanced aid and investments to Afghanistan and has been articulate about its intention of being the major player in Afghanistan’s economic reconstruction, especially through the OBOR. However, the question of how Afghanistan is to be connected to the OBOR remains unanswered, as the country presents a complex case for the OBOR. This is because the withdrawal of the US and NATO from Afghanistan will have negative effects on China’s economic engagement with Afghanistan. While China has taken a number of steps to address the security situation, it will not replace the US and NATO’s role in Afghanistan. China will, therefore, be reluctant to release its plans for Afghanistan until there is degree of certainty regarding the security situation in the country. Proposed routes, such as the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB) and China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), therefore, go around Afghanistan, rather than linking it. The border between China and Afghanistan is mountainous and located in the Wakhan corridor, making it necessary to develop a special corridor to directly link Afghanistan to the OBOR. China has committed only USD 100 million to Afghanistan under the project, while it has committed USD 46 billion to Pakistan and USD 31 billion to Central Asian countries.

This is similar to the fate of previous Chinese investments in Afghanistan. The MesAynek project has not been operationalized due to Chinese security concerns. The MCC backed down from infrastructure investment that was promised around the site. The Amu Darya project had also faced delays and its promise to build an oil refinery in northern Afghanistan has not materialized. While China has made these projects an important part of its narrative on economic reconstruction in Afghanistan, it is important to note that other than these projects, China has only given Afghanistan USD 250 million since 2001, and has made a commitment of USD 327 million by 2017. This is an insignificant amount compared to the USD 110 billion support from the US for economic reconstruction in Afghanistan since 2002.

The inability of the government to take leadership of the country’s economy will also hamper the country’s ability to benefit from the OBOR. It is noted for nepotism, corruption and its inability to uphold the rule of law; and has not fulfilled its promise of coordination and teamwork among various groups and political blocks to achieve economic development. For instance, Afghanistan’s role as a regional transit hub and supplier of energy will depend on the government’s ability to handle the industry, which is characterized by illegal mining and non-payment of royalties. However, the government has shown reluctance to take action against criminal networks in the industry. Further, various investments in Afghanistan have not been operationalized due to lack of a favourable environment. An example of this is the Chinese private company Xinjian Bexin which has not completed its 2013 plan to rehabilitate a road from Kabul to Jalalabad due to the difficult operating situation.

Conclusion

The OBOR has the potential to pave the way for Afghanistan’s economic development by enhancing its participation in intraregional trade through improved connectivity. This will improve its trade balance by enhancing exports, and reducing costs of imports. Increased income from trade in goods and energy can be reinvested in the infrastructural development of the country, thereby reducing its dependency on foreign assistance, and enabling sustained economic stability and growth.

However, this can be realized only in the face of a coherent government policy aimed at enabling Afghanistan’s participation in the OBOR. While China is an important investor in the country, it is likely that China will remain aloof rather than interfering in the domestic issues of the country. This is illustrated in China’s repeated call for an ‘Afghan led, Afghan owned’ process of development. In this scenario, the government must lead the way by taking initiative for developing small-scale energy or transport infrastructural projects to integrate with the OBOR. A unified government that can establish a favorable environment for the operationalization of projects will encourage foreign investors and traders. This is possible by ensuring easy access to information and curbing corruption in administration. Another important step is to engage the private sector as an important player to facilitate the country’s growth and development and also encourage regional integration.

Afghanistan’s meaningful participation will not only depend on improved infrastructure but also through addressing the specific issues of low productivity of the agricultural sector and the lack of development of the industrial sector. The government must undertake structural transformation of the economy, through a special focus on domestic agriculture and industry to take advantage of OBOR facilitated connectivity. This will not only boost exports, but also reduce Afghanistan’s dependence on imports, thereby making its balance of trade more favourable. One means to do this is to focus on policies to boost the manufacturing sector by setting up special economic zones. Afghanistan must attempt to enter the global value chain for agriculture through diversification of products and promotion of high value cash crops such as saffron, targeting large markets in the Middle East and South Asia. This will allow the country to boost its earnings through high value added exports. In order to improve Afghanistan’s export potential in intraregional trade as facilitated through the OBOR, the country must seek to improve relations with neighbouring countries in order to resolve issues surrounding cross border trade and transit. Rather than looking at China as the singular source of political and economic stability in the region, the government must exercise political leadership over the process of economic development in order to achieve benefits from the OBOR project.

References

“One Belt One Road: One Stone Kills Three Birds.” BNP Paribas Report (24 June 2015). http://institutional.bnpparibas-ip.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Chi_Lo_Chi_on_China_China_One_Belt_One_Road_Part1.pdf

Ahmad, Talmiz. “Silk Road to economic heaven.” Dawn (18 June 2016). http://herald.dawn.com/news/1153432

Aneja, Atul. “Silk Road train to reach Afghanistan on Sept 9.” The Hindu (28 August 2016).http://www.thehindu.com/news/international/chinas-first-cargo-train-to-afghanistan-fuels-one-belt-one-road-obor-engine/article9042851.ece

Byrd, William. “What Can be Done to Revive Afghanistan’s Economy?” USIP Special Report (2016).https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/SR387-What-Can-Be-Done-to-Revive-Afghanistans-Economy.pdf

Chene, Hugo. “China in Afghanistan: Balancing Power Projection and Minimal Intervention.” IPCS Special Report 179 (2015).http://www.ipcs.org/pdf_file/issue/IPCSSpecialReport_ChinainAfghanistan_HugoChene.pdf

Clarke, Michael. “‘One Belt, One Road’ and China’s emerging Afghanistan dilemma”. Australian Journal of International Affairs 70:5 (2016).

Clarke, Michael. “China’s Emerging Af-Pak Dilemma.” China Brief 15:23 (7 December 2015).http://www.jamestown.org/programs/chinabrief/single/?tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=44867&cHash=568e6fe498e9245d5d5b1c1704f5253c#.V9mIPIQxHeR

Clover, Charles and Lucy Hornby. “China’s Great Game: Road to new empire.” Financial Times (12 October 2015).https://www.ft.com/content/6e098274-587a-11e5-a28b-50226830d644

Downs, Erica. “China Buys into Afghanistan.” SAIS ReviewXXXII:2 (Summer-Fall 2012). https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/China-Buys-into-Afghanistan-Erica-Downs.pdf

Huasheng, Zhao. “Afghanistan and China’s new neighbourhood diplomacy.” International Affairs 92:4 (2016).

Martina, Michael and MirwaisHarooni. “Slow road from Kabul highlights China’s challenge in Afghanistan.” Reuters (22 November 2015). www.reuters.com/article/afghanistan-china-road-idUSL3N13D2ZM20151122

Mohmand, Abdul. “The Prospects for Economic Development in Afghanistan.” Asia Foundation Occasional Paper 14(14 June 2012), https://asiafoundation.org/resources/pdfs/ProspectsofEconomicDevelopmentinAfghanistanOccasionalPaperfinal.pdf

Muddaber, Zabihullah. “Where Does Afghanistan Fit in China’s Belt and Road?” The Diplomat (3 May, 2016).http://mantraya.org/failure-of-institutionalised-cooperation-in-south-asia/

Pantucci, Raffaello and Qingzhen Chen. “One-Belt One- Road”: China’s Great Leap Outwards.” China in Central Asia (18 June 2015).http://chinaincentralasia.com/2015/06/18/the-geopolitical-roadblocks/

Siddique, Abubaker. “New Chinese Grand Strategy to Help Afghanistan.” Gandhara(29 October 2015).http://gandhara.rferl.org/a/china-afghanistan-one-road-one-belt/27334055.html

Tran, Tini. “Beijing Panel Explores Stabilising Afghanistan: A Role for the Neighbours?” Asia Foundation (8 July 2015).http://asiafoundation.org/2015/07/08/beijing-panel-explores-stabilizing-afghanistan-a-role-for-the-neighbors/

Zhou, Andi. “Can China’s ‘One Belt, One Road’ Save the US in Afghanistan?” The Diplomat (11 March 2016).http://thediplomat.com/2016/03/can-chinas-one-belt-one-road-save-the-us-in-afghanistan/

Zimmerman, Thomas. “The New Silk Roads: China, the US, and the Future of Central Asia.” NYU Center on International Cooperation (October 2015). http://cic.nyu.edu/sites/default/files/zimmerman_new_silk_road_final_2.pdf_

(Nivedita Jayaram is a project intern with MISS and is associated with Mantraya’s “Regional Economic and Cooperation and Connectivity in South Asia” project. All Mantraya publications are peer-reviewed.)