MANTRAYA ANALYSIS#12: 30 MARCH 2017

BIBHU PRASAD ROUTRAY

Abstract

Declining ability among the left-wing extremists (LWE) to orchestrate attacks and the state’s purported capacity to find support among the traditional recruitment base of the Communist Party of India-Maoist (CPI-Maoist) are the primary reasons for the official optimism regarding the LWE situation in the country. And yet, the extremists do manage to carry out intermittent major as well as small scale attacks. Sizeable territory in the country remains under the control of the extremists. A solution to the problem that began 13 years ago with the formation of the CPI-Maoist does not look imminent.

(Injured CRPF personnel being evacuated after an attack by the CPI-Maoist

in Chhattisgarh’s Sukma district in March 2017)

Sense of Optimism

On 17 March 2017, India’s Home Minister Rajnath Singh told the parliament that the number of left-wing extremism affected districts in India has declined from 106 to 68. Of these 35 districts are in the ‘most affected’ category, meaning that bulk of the extremist violence is concentrated in these districts. In a neatly planned attack, the Communist Party of India-Maoist (CPI-Maoist) killed 12 members of the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) in Chhattisgarh’s Sukma district on 11 March, six days before Mr. Singh’s statement. The reality of shrinking extremist footprints, thus, must include capacity of the extremists to carry out sporadic as well as small scale violence in areas under their control and their ability to implement their diktats affecting the lives of the common civilians. In spite of repeated official statements of optimism that LWE would be over soon, this is how the extremist situation is likely to evolve in the coming months.

The Crouching State

Official counter-LWE policy remains multifarious approach consisting of use of force, initiation and implementation of development schemes, perception management, and political activity in the regions liberated from the extremist control. Under the present Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government, however, use of force has gained pre-eminence. The approach is based on the premise that neutralising the top leadership of the CPI-Maoist would not only weaken the movement but may lead to its complete disintegration. Since May 2014, the year the BJP came to power, security forces have killed at least 464 extremists in various affected states. Precedents in Andhra Pradesh (where success was derived by the neutralisation of several top leaders) and West Bengal (where the killing of the senior leader Kishenji led to a total collapse of the movement) form the foundation of such a policy that include: an increase in the deployment of central armed police forces (CAPFs),and effecting a paradigm shift that designates LWE as terrorism. An alternative to a predominantly force centric policy is unlikely to be explored.

Beginning with the Salwa Judum experiment where the Chhattisgarh police supported a vigilante movement until it was dissolved by an order of the Supreme Court, various states have attempted to supplement police operations against the extremists by seeking support of the local people, dependence on the vigilante as well as irregular forces is likely to continue. In Chhattisgarh, the Salwa Judum has been regularised in the name of District Reserve Guards (DRG), who in the recent past have been credited with leading a large number of successful operations against the Maoists. Such reliance on the irregular forces and vigilante groups, in the absence of police capacities, remains a critical necessity and hence, would continue, even amid the allegations of human rights violations.

Under the BJP government, the counter-Maoist operations have continued with less-than-usual focus on human rights violations. Overzealous police officials, especially in Chhattisgarh, in a bid to secure popular support, have used vigilante groups to persecute the activists, lawyers, media personnel in the affected areas. However, such actions have increasingly come under intense scrutiny at the national level requiring judicial intervention. As a result, accused police officials had to be transferred and stripped off their role in such operations. The state’s continuing inclination to silence voices that highlight the plight of the tribals caught between the irresponsible and poorly led security forces on the one hand and the Maoists on the other will remain subject to pressures from intense activism. This may lead to some level of moderation in the force-centric counter-insurgency (COIN) approach, albeit at a superficial level.

In spite of the drawbacks in training, command and control loopholes and problems of intelligence gathering, significant achievements have been secured by the security forces vis-a-vis the Maoists. Vast stretches of areas have been cleared and several infrastructural projects continue to be implemented due to the dedicated presence of the security forces. Development initiatives of the state in areas freed from LWE control remain key to the future success of the state. And yet, the abysmal quality of governance, lack of a committed bureaucracy and continuing schism between the local population and the bureaucracy will make centralised developmental initiatives attempts subject to tough challenges in 2017. Measures such as filling up posts of doctors and nurses in hospitals in the affected areas, filling up the vacant position in schools, providing road networks would just not be delayed by the threat of the extremists, but also by the lethargy and corrupt practices of the state bureaucracy.

Extremist Strategy

The CPI-Maoist leadership admits its loss of influence due to a series of tactical failures. This makes two key objectives- (i) maintenance of its relevance and (ii) preserving and expanding its cadre strength- central to its near and long term strategy. The outfit would attempt to mix defensive as well as offensive manoeuvres to preserve its cadres and inflict casualties on its adversary. The CPI-Maoist partially succeeded in its objective on 2016 by killing more number of civilians and security forces than the previous year. Casualties among civilians and security forces rose from 230 in 2015 to 278 in 2016. 20 arms training camps were organised in 2016 compared to 18 in the previous year. The ‘police sympathisers’ are likely to become a key target of the outfit in its bid to regain control over the lost territories. In 2016, the outfit killed 123 such state-sympathisers, most of them belonging to the tribal population. in 2015, such killings were 23 percent less.

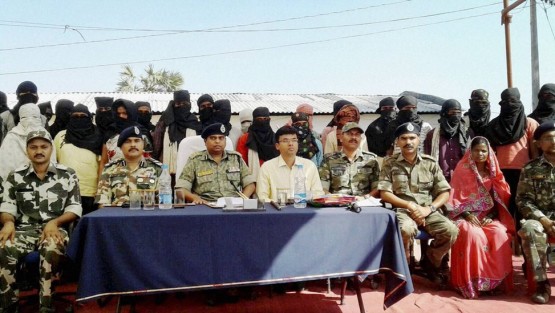

(A surrender ceremony of CPI-Maoist cadres in Chhattisgarh)

History of LWE in general and that of the CPI-Maoist in particular has been marked by an ideological tussle between leaders. One group led by Kanu Sanyal suggested a gradual process of revolution with popular participation and the other led by Charu Mazumdar opted for an instant revolution using armed cadres. Although the CPI-Maoist led by its general secretary Ganapathy more or less settled for the latter, the contestation between its political wing and its military wing over the momentum of its war, trajectory of its violence, and the targets chosen continued. In its weakened state the CPI-Maoist is likely to override any such distinction and opt for a strategy that seeks to make a violent war its only path for redemption.

Like any guerrilla organisation, the CPI-Maoist has sought to utilise the terrain, the commitment of it cadres and it intelligence network to battle a superior enemy. It has used innovation to add quality to its attacks. Planting explosives inside the bodies of killed security forces and on trees, and planting remote controlled IEDs underneath tarred roads to inflict casualties on the forces are instances of such innovations. Huge amount of explosives in single attacks have been used to overcome the resistance offered by mine proof vehicles. In recent times such as the one that took place in Chhattisgarh’s Sukma district, explosives mounted on arrows were used. The CPI-Maoist has also used the L and S-shaped hilly areas to carry out attacks in the past. The same technique is now being used to its advantage in flat terrains as well.

Programmes for consolidating support among its traditional base, i.e. the tribal population would remain a critical pillar for the CPI-Maoist’s attempts of maintaining its relevance. The outfit uses a carefully constructed strategy of communication, assisted largely by voluntary efforts, to deride the state and promote itself as the liberator of the marginalised class. Using the contemporary political developments in the country, especially the pro-market economic policies of successive governments as well as the surge in right wing politics as ideological underpinnings, it constantly calls for unity of purpose among the tribals, working class, trade unions and even sympathetic urban intelligentsia. Such efforts would continue and may even assume the form of greater emphasis on communication through electronic and international media.

Expanding the area under its influence, especially to overcome the challenges of shrinking dominance, would be a strategic objective for the CPI-Maoist. Narratives in the past have pointed at Maoist activities in Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Karnataka. Much of such efforts, in the short term, would be based on strategic requirements of finding hiding space as well as dividing the attention of the security forces. How do the states unfamiliar with the Maoist expansion techniques respond to such slow and essentially violence free attempts of finding influence would define the state’s success against the extremists.

Forecast

The state will retain military advantage over the extremists. However, that alone would not be sufficient to decimate the CPI-Maoist. Retreating extremists as a result of a force centric approach will lead to the creation of areas where the state exercises its control only through its security arm. It will, however, a temporary phase where the balance will be tilted in favour of the state. Without an effective strategy to implement development schemes and avoidance of mistakes that worsen the agony and alienation among the tribals, such areas will remain fertile grounds for extremism to return.

References

- “150% jump in killing of Naxals in 2016: Govt. tells Lok Sabha”, The Hindu, 21 March 2017, http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/150-per-cent-jump-in-killing-of-naxals-in-2016-govt-tells-ls/article17555296.ece

- “474 civilians killed in Naxal violence in Gadchiroli since 82”, India Today, 10 March 2017, http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/474-civilians-killed-in-naxal-violence-in-gadchiroli-since-82/1/901885.html

- “Number of naxal-affected districts reducing: Home Minister Rajnath Singh”, Economic Times, 17 March 2017, http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/number-of-naxal-affected-districts-reducing-home-minister-rajnath-singh/articleshow/57694358.cms

- Sanjeev K Ahuja, ” Maoist-affected states fail to offer youth jobs”, Hindustan Times, 20 March 2017, http://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/maoist-affected-states-fail-to-offer-youth-jobs/story-blZoT9TGReZ7qzIKZm9izK.html

- Vijaita Singh, ” 12 CRPF personnel killed in Naxal attack in Chhattisgarh”, The Hindu, 11 March 2017, http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/11-crpf-personnel-killed-in-naxal-attack-in-chhattisgarh/article17446850.ece

(Bibhu Prasad Routray is the Director of MISS. This analysis is a part of Mantraya’s “Mapping Terror and Insurgents Networks” project. All Mantraya publications are peer-reviewed.)