MANTRAYA POLICY BRIEF#24: 01 DECEMBER 2017

BIBHU PRASAD ROUTRAY

Abstract

It is the season for home coming. With the Caliphate of the Islamic State collapsing in Iraq and Syria, the surviving among the outfit’s 40,000 foreign fighters are now faced with three options-to die fighting, to move into new conflict theatres in an attempt to relive the dream of a Caliphate, or to return to their home countries. It is the third option which is now making many countries nervous. How to manage such returns and what to do with these fighters once they return? What impact can they have on conflict theatres such as Kashmir?

(Anti-Islamic State fighters in Iraq in 2016, Photo Courtesy: Reuters)

The Islamic State reportedly kept detailed records of its fighters. These records some of which were obtained by German intelligence, in addition to the recovered computers and smart phones, have helped create a profile of nearly 22,000 names which has been shared with Interpol. The attempt is to arrest these fighters at the source and not let them have a free run into a new conflict theatre or not certainly, into their home country.

During a conference on transnational crime in Taipei organised by the Ministry of Justice’s Investigation Bureau (MJIB) in October 2017, I spoke to a senior official of Australian Department of Immigration and Border Protection about the challenge the Islamic State foreign returnees pose to the country and how his department has prepared to deal with it. According to him, the department has a database of each and every 200 Australians who have left the country’s shores to Syria and has implemented a programme for their ‘managed’ returns. “Nobody will not spring a surprise on us”, he told, “by showing up at the airports”. Few of the passports of such people have been cancelled. Arrangements have been made and officials have been posted at airports in Turkey from where such return journeys are most likely to begin. He hoped that most of the foreign fighters will not return to the country because none of them can potentially be integrated into the society.His voice echoed opinion by a UK minister Rory Stewart who said that each of the British nationals who joined the Islamic State must be killed and should not be allowed to return to the country. Such assertions, however, have coexisted with arrangements to provide safe haven to Islamic State fighters. Such a project in Raqqa, reportedly overseen by British and American forces, while facilitating an early declaration of victory in previous Islamic State strongholds, has made the return of foreign fighters indeed a real and present danger.

While the authenticity and scale of the BBC’s report remain unverifiable, at one level the mindset that the Islamic State’s fighters should perish in Syria and thereby sparing the respective countries of their origin from serious troubles is symptomatic of the absence of an official policy on these radicalised individuals. At the other, it underlines the danger the governments perceive these returnees would bring back with them and how such dangers would not be eradicated by merely putting them behind bars.

The Indonesian government, for instance, has struggled to deal with the hundreds of such people who have been deported from Turkey. Most, according to the NGOs who are working among them, display signs of intense radicalisation and have expressed their desire to return to Syria and Iraq, in spite of the fact that the Caliphate has almost ceased to exist in such countries. The Indonesian government follows a procedure of collecting signatures of these returnees on paper where they also are required to swear allegiance to the state’s constitution and its Pancasila ideology. Most returnees reportedly have refused to sign such documents. The NGOs also say that their attempts to initiate a de-radicalisation process by making these people clap and sing has attracted a zero response as singing and clapping are labelled as ‘haram‘ (unIslamic) by these returnees.

(Protesters in Kashmir carry flags of the Islamic state in 2015, Photo Courtesy: India Today)

In comparison, India’s problems are different from Australia, European or Southeast countries and are more complex.

Close to 250-300 Indians have actually attempted to or succeeded in travelling to Iraq and Syria to join the Islamic State. Of them, around 100 have joined the Islamic State and travelled to the territories under the control of the group in Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan. These include people from India as well as Indians employed in different countries, mostly in the Gulf. While only a handful have been deported or returned, about 15 of them have reportedly been killed while fighting there. The last such reported death was that of Fahad Shaikh, one of the four young men from Kalyan (in Maharashtra) who travelled to Syria in 2014 to join the outfit. If his death reported in October 2017 is indeed true, the Kalyan team, one of the first such groups to heed the call of the Islamic State, has been completely finished. Only one of the four, Areen Majeed, managed to return and has since been spending time behind bars. Also in October, deaths of five men who had travelled from Kannur district of Kerala to Syria were reported. According to the Kerala police, these men, aged between 20 and 45, died in Syria at various periods of time between 2014 and 2017. In September 2017, another man from Kerala, 30 year old Mohammad Shajil was killed while fighting for the Islamic State. Shajil’s death left his wife Hafziya and two children who had travelled with him to Syria in — without any support.Many women like Hafziya had accompanied their husbands without knowing that they were being taken to Islamic State territories.In August, the Islamic State’s Amaq media agency claimed that Shafi Armar, the outfit’s 30-yearold recruiter for India has been killed in a suicide attack in Syria. The claim, however, has been termed as unreliable by Mumbai’s Anti-terrorism Squad.

Given that no estimate of foreign fighters of Indian origin exists in the database of organisations who track such movements (mostly because such estimates depend largely on home country’s official assessments and media reports and India, like many non-western countries, tries to underplay the fact that Indians are joining global jihadist organisations like the al Qaeda and the Islamic State), one can only attempt an intelligent and conservative guess on the number of such people. Based on my interactions with Indian intelligence agencies and monitoring of Islamic State media reports since 2014 by Mantraya, the number of Islamic State’s foreign fighters from India (including those of Indian origin) who could be alive today is less than 50 (without including their family members). Thus, we are looking at a scenario when some of these men are seeking to return to the home country.

Government of India maintains that radicalisation among the Indian Muslims is low. On 11 November, Home Minister Rajnath Singh said, “Muslims in India, when compared to Muslims elsewhere, are less radical…. We do not face the threat of the ISIS because of this.” However, while this may have been true in the past, the Jihadist landscape in India in general and in Kashmir in particular has changed significantly in the past months.

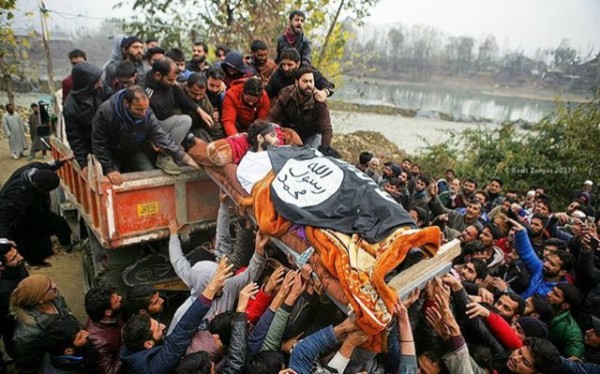

(Islamic State flag on the body of killed militant Mugees Ahmad Mir in Kashmir

in November 2017, Photo Courtesy: Greater Kashmir)

Some sections within Kashmir’s militant movements have indeed started responding favourably to the three year-old attempts by the al Qaeda and the Islamic State to gain foothold in the region. This symbiotic relationship between the fledging global jihadist movements and the desperate-for-success local militancy has taken the form of the Islamic State setting up a dedicated Telegram channel for Kashmir and the al Qaeda providing its brand name to a group of militants who have moved out of the Hizb-ul Mujahideen (HM) and established the Ansar Ghazwat-ul Hind. In response, solitary incidents of waving of Islamic State’s flags have now become regular. Graffiti declaring certain portions of Kashmir towns as al Qaeda or Islamic State territory have appeared. On occasions Islamic State flags have appeared on the dead bodies of militants killed in encounters, replacing the traditional practice of draping them with the national flag of Pakistan. And the new crop of leaders has increasingly started talking about their struggle being directed at establishing an Islamic Caliphate in Kashmir. All this makes the first phase of partnership between the sections within the local militants and the global jihadist organisations complete. Interestingly, both the al Qaeda and the Islamic State could also be, at least for the time being, cooperating with each other in Kashmir. Not surprisingly therefore, on some occasions, Islamic State’s flags have been draped on the dead bodies of militants who have sworn allegiance to the al Qaeda. The latest of this trend includes Mugees Ahmad Mir alias Khatib of Ansar Ghazwat-ul Hind who was killed on 17 November. Notwithstanding the Islamic State’s clumsily worded (where it claimed to have killed ‘a Pakistani police officer in ‘an immersive operation’ in Srinagar) and disputable claim over the encounter in which Mugees was killed (the local outfit Tehreek-ul-Mujahideen also claimed Mugees as one of their commanders), Kashmir could indeed be transforming itself into a more hospitable place for growth of global Jihadists and also to host the Islamic State returnees.

Both the al Qaeda and the Islamic State have attempted to widen their appeal beyond Kashmir. The al Qaeda in the Indian Sub-continent (AQIS) has begun online distribution of Tamil, Bengali and Hindi translations of key jihadists. A recent audio clip by the Islamic State, transmitted via Telegram app, calls for attacks on Hindu religious congregations such as Kumbh or the Thrissur Pooram. In the clip, Abdul Rashid, an Islamic State recruiter who travelled from Kerala to Afghanistan in 2016 has asked Indian Muslims to launch attacks by driving a truck through devotees or poisoning food.One needs to ponder whether these are mere rhetoric, or an extension of the new found confidence riding on the inroads made in Kashmir.

While India still may be able to stop direct flights of Islamic State’s foreign returnees, a travel plan routing them through Pakistan where the support for the Islamic State continues to grow and Afghanistan where the Islamic State has some of its Indian cadres (mostly from Kerala) is not implausible. Getting into Kashmir from those locations is comparatively easier. Sooner than later, New Delhi may encounter these challenges and may find that a policy of denial and information suppression isn’t adequate enough.

(Bibhu Prasad Routray is the Director of MISS and currently Visiting Professor and India Chair at Murdoch University, Perth. This Policy Brief has been published as part of Mantraya’s ongoing “Mapping Terror and Insurgent Networks” and “Islamic State in South Asia” projects.)