MANTRAYA ANALYSIS#02: 26 APRIL 2015

SHANTHIE MARIET D’SOUZA

Abstract

The pessimism in New Delhi’s strategic circles emanating from Kabul’s tilt towards Pakistan and China notwithstanding, President Ghani’s visit can mark the beginning of a clear road map of India’s engagement strategy to protect its key national interests and help in the long term stabilisation of Afghanistan. For that to occur, New Delhi would need to revisit its policies in Afghanistan, moving away from asset creation to a level of engagement that builds up Afghanistan’s economic, political and social capital based on Afghan needs and priorities in the transformation decade.

Thirteen months after the then external affairs minister Salman Khurshid promised to deliver helicopters to Afghanistan, New Delhi has transported three Cheetal helicopters to Kabul. The training component of the transfer has been completed and the announcement of the delivery will be made during President Ghani’s visit to India. Cheetal is an upgraded Cheetah (Alouette) helicopter with a newer Turbomeca TM 333-2M2 engine. These choppers are capable of operating in remote and high altitude mountainous region with higher speed (more than 200 km/hr), range (more than 600 km) and payload. The Cheetal can be used for personnel transport, casualty evacuation, reconnaissance and aerial survey, logistic air support and rescue operations. As the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) face increasing insurgent onslaught, the need for airpower is critical gap that New Delhi intends to address in buttressing the capability of the Afghan Air force.

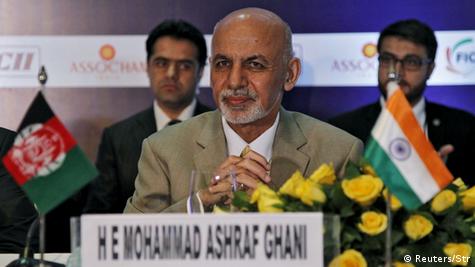

Coming days ahead of Afghan President Ashraf Ghani’s visit to New Delhi, from April 27 to 29, the delivery of helicopters is a significant development, going somewhat against its policy of seeking influence in Kabul through aid giving and yet avoiding getting directly embroiled in the conflict. At a time of the international drawdown of troops combined with President Ghani’s increasing tilt towards Pakistan and China, these supplies is seen as New Delhi’s continued attempts to maintain its relevance in the new emerging power and security calculus in Kabul. Agreements on mutual legal assistance, motor vehicles movement and between chambers of commerce are also under discussion ahead of President Ghani’s visit.

Following his inauguration as the President of Afghanistan, Mr Ghani, an anthropologist and a former World bank official had declared Pakistan to be his priority. India was seen to have relegated to the outer rings of a ‘five circle’ foreign policy. Ghani visit’s to Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and China and his March 2015 visit to the United States has further been interpreted by analysts in New Delhi as India’s waning influence in Kabul. Ghani maintains that he is cautiously optimistic about his relations with Pakistan. Following the Taliban attacks on the army school in Peshawar in December 2014, Pakistan is looking at expanding their counter-terrorism cooperation with Afghanistan, with the latter’s support forming a critical part of Islamabad’s strategy to eliminate the threat from Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) . The other parameters of Afghan-Pakistan cooperation is the training of Afghan cadets in Pakistan’s Military Academy (PMA) in Abbottabad. In February 2015, the first batch of six Afghan cadets arrived at PMA to undergo an 18-month long course. In addition, seen as a move to allay Pakistani anxiety of increased Indian involvement in the security sector, Ghani had put aside his predecessor’s military aid requests from India.

The timing of the supply of the helicopters, thus, comes at an interesting point of regional power competition for influence in Kabul. The development of a Pakistan-China axis is visible. Recently China has evinced interest in playing a role in facilitating talks with the Afghan Taliban, in addition to stepping up its security assistance to Afghanistan. In exchange it hopes to enlist the assistance of Pakistan to counter the threat of the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), the Uighur separatist group which shares links with the Taliban. Beijing, in addition, has significant economic interests in Afghanistan. An increased Pakistan-China influence, following the Chinese premier’s April 2015 visit to Pakistan, is viewed as offsetting India’s plans of maintaining its influence in Kabul.

Post-2001 New Delhi’s has invested in various infrastructure, capacity building, health, education and economic reconstruction. Having pledged US$2bn, India is the largest regional donor and Afghanistan is the second largest recipient of Indian aid. India’s aid and development assistance has accrued significant ‘good wil’l among the Afghans. While Afghanistan makes domestic and regional alignments in the transformation decade (2015-2024), whether President Ghani’s visit can mark the beginning of a clear road map of India’s engagement strategy to protect its key national interests and help in the long term stabilisation of Afghanistan remains to be seen.

The increased presence of the Lashkar-e-Toiba (LeT) and its capability to strike was evident during the attack on the Indian consulate in Herat in May 2014. Armed and well prepared for a hostage taking situation, LeT’s intent to execute the plan was thwarted by the help of the Afghan domestic intelligence agency, the National Directorate of Security (NDS). In May 2015, LeT had planned to carry out the strikes in India, coinciding with Pakistan Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s presence in New Delhi for the inauguration of the Modi government. The kidnapping of the Jesuit priest Alexis Prem Kumar from Herat in June 2014 and his subsequent release after eight months in captivity in Helmand further underlines the complexities of the security landscape in Afghanistan.

The splintering of the Taliban insurgency and its functioning through franchisees; increased presence of criminal networks who have resorted to ransom demands add to the challenges. Increased LeT influence could further complicate implementation of Indian funded aid schemes. For denying the extremists groups the space to strike Indian interests and destabilize Afghanistan, New Delhi’s near to medium-term projects need to increase training and capacity building of the Afghan national security forces (ANSF), particularly its officer corp; the police, and the air force, and institutional support to improve Afghan Ministry of Defence (MoD) in its planning and budgeting process. In the long-term, security sector reform and assistance in building sound civil-military relations are some of the other initiatives New Delhi can assist Kabul with.

While India has worked towards shoring up the Afghan government’s capacity, the delivery of aid through support to Afghan budget would remain crucial to help the state extend its writ and provide basic services. India’s aid and assistance could make a greater impact if it shifts away from high visibility projects aimed at one time asset creation. An enduring Indian influence would remain linked to New Delhi’s ability to design and help implement development programmes to address poverty, illiteracy and systemic administrative dysfunction, as much as the timely completion of continuing projects such as the Salma Dam and construction of the Afghan Parliament building. The Small Development Projects (SDPs) which are implemented in southern and eastern Afghanistan in sync with local needs and ownership need further expansion. Likewise, greater investment in Afghan public health sector and educational initiatives like computer literacy, skill building and employment generation opportunities would help build the social and economic capital. India has actively provided assistance to women groups either through self-employment schemes, health and capacity building not only in Kabul but also in the western province of Herat. This needs to be expanded to areas in the South and East. My discussions with women groups in Kandahar brought out the need for small-scale income generation activities, and the need for improved health facilities.

In the political sector and governance, New Delhi needs to play an enabling role in institution building processes. In addition to broad based engagement with the political elite, New Delhi needs to work on the political sector reform involving greater decentralisation and strengthening the electoral processes. The past presidential and parliamentary elections in Afghanistan have brought to fore the problems of a highly centralised presidential system. While India has supported an Afghan-led reintegration and reconciliation process, adherence to the red lines laid down at the London Conference including respect for the Afghan constitution, human and women rights would be crucial. Afghanistan’s attempts at reconciliation needs to be supported by larger political and constitutional reforms which would necessitate provisions for dialogue and special representation of minorities, women and marginalised groups.

In aiding economic stabilisation, in the near and medium term, India could help in establishing small and medium enterprises (SME), alternate livelihood programmes (in poppy growing areas) and revive the Afghan indigenous economic base. In Baba Saheb Ghar in the Arghandab Valley, traditionally known for its pomegranates, locals seek help in establishing storage, processing and transit facilities. In discussions with political leaders in Kandahar on 5 October 2011, a day after the Agreement of Strategic Partnership Agreement (ASP) between New Delhi and Kabul was signed, they expressed an immediate need for setting up cement factories, irrigation and power projects in the province in addition to building roads and improving health and educational facilities. Natural resource exploration, power generation and industrial development would provide opportunities for employment for the youth. Moreover, it would help Afghanistan to transition from being an externally aid dependent ‘rentier state’ to a self sustaining economy.

Afghanistan, due to its small manufacturing regime, is swamped by foreign goods mainly from Pakistan, China and Iran. This inhibits the growth of an indigenous economic base. India could contribute to the small-scale industries sector (carpets, ornaments and handicrafts). Follow up studies on these projects, assessing their usefulness and links with the development strategy of the Afghan government, would be extremely critical. As Afghanistan faces a contraction of its economy due to dwindling international financial assistance, it will be imperative to help Afghanistan generate revenue and realize its potential as a land bridge connecting South with Central and West Asia. Increased trade, transit and regional connectivity would provide revenue and employment opportunities and in the long term help build ‘constituencies of peace.’ Implementation of the Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India (TAPI) pipeline and expansion of the Afghanistan Pakistan Trade and Transit Agreement (APTTA) to India would provide economic benefits to all countries in the region and create a ‘web of interdependencies’.

India needs to further build on its traditional, historical, social and cultural linkages with Afghanistan. As part of counter radicalisation campaign, messages of moderate Islam from the Deoband would be an effective counter to the radical Wahhabi messages. There is also a need to further expand cultural, sports and educational exchanges between the two countries. Setting up of Pushtun and Dari centres in India and Hindi centres in Afghanistan would help in greater cultural and linguistic exchanges. Cricket is an important sport that needs promotion. In addition to building a cricket stadium in Kandahar, India can assist in providing a home ground for the Afghan national cricket team in India, a wish President Ghani is reported to be carrying with him.

Most of the international media puts out pessimistic stories from Afghanistan. It influences not only international public opinion but also feeds into the insurgent propaganda. It is imperative to have a strategic communications strategy highlighting the positive stories of success of the Afghan people (rather than violence, destruction and pessimism) through the radio, television and local print media. During my visits to Jalalabad, there have been requests for capacity building, collaboration, training and programmes on historical, cultural, educational and sports. New Delhi can help shift the narrative of pessimism to opportunity by increasing capacity building and cooperation with the Afghan media and engaging civil society, women and youth groups.

More importantly, New Delhi will have to assist in reviving the indigenous economic base and connecting Afghanistan – the Heart of Asia- with rest of Asia. The economic interdependency and benefits would create a mutually beneficial mode of engagement in the region. President Ghani’s visit can mark the beginning of a clear road map of India’s engagement strategy to help in the long term stabilisation of Afghanistan and the region.

(Shanthie Mariet D’Souza is the Founder and President of MISS. All Mantraya publications are peer-reviewed.)