MANTRAYA SPECIAL REPORT#21: 23 JANUARY 2023

BIBHU PRASAD ROUTRAY

ABSTRACT

Hopelessly stuck in the wretched camps in Bangladesh for over five years, Rohingya refugees are undertaking perilous sea journeys to Malaysia, across the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea. While thousands have reached their destination in search of better lives, hundreds have sunk into the sea. As such journeys are likely to continue, a comprehensive plan supported by adequate and regular funding to improve the living conditions in the camps, pending their repatriation to Myanmar, needs to be developed.

Introduction

Sometime in December 2022, an overcrowded boat carrying 180 Rohingya refugees from Bangladesh sank in the Andaman sea.[1] Another boat, with nearly 200 hundred hungry and emaciated refugees on board, washed up in Indonesia’s Pidie district in Aceh province. Indonesian authorities initially refused to allow the passengers to disembark, pledging instead to repair the boat and then send it back out to sea. But amid an outcry from rights groups, the United Nations (UN), and local residents, the government brought the refugees ashore. A separate group of 58 male Rohingya refugees was pulled ashore by locals, also in Aceh. One more boat in distress was towed to safety by Sri Lankan Army. A Vietnamese oil service vessel in the Andaman sea decided to surrender 154 passengers of yet another sinking boat to Myanmar.[2] All these incidents have taken place within a time span of fewer than four weeks between December 2022 and the first week of January 2023. What also happened amid such distress migration is the Myanmar government’s decision to send over 100 Rohingya refugees including children below five years to prison for attempting to leave the country illegally.

The Rohingya have been desperate to travel out of Bangladesh and Myanmar, forsaking their wretched existence as refugees and unwanted persons, for better avenues in Southeast Asian countries like Malaysia. According to the UN, between January 2020 and June 2021, more than 3000 Rohingya have attempted to journey from Bangladesh by sea, with women and children accounting for two-thirds of them. Human Rights Watch says that the Myanmar junta has arrested an estimated 2000 Rohingya for “unauthorised travel” since the 2021 coup, with many being sentenced to up to five years in prison. However, while many of the refugees manage to reach their destination, for many others these turn out to be roads to perdition, with significantly high chances of death, due to starvation or disease on board.

Life in Bangladeshi Camps

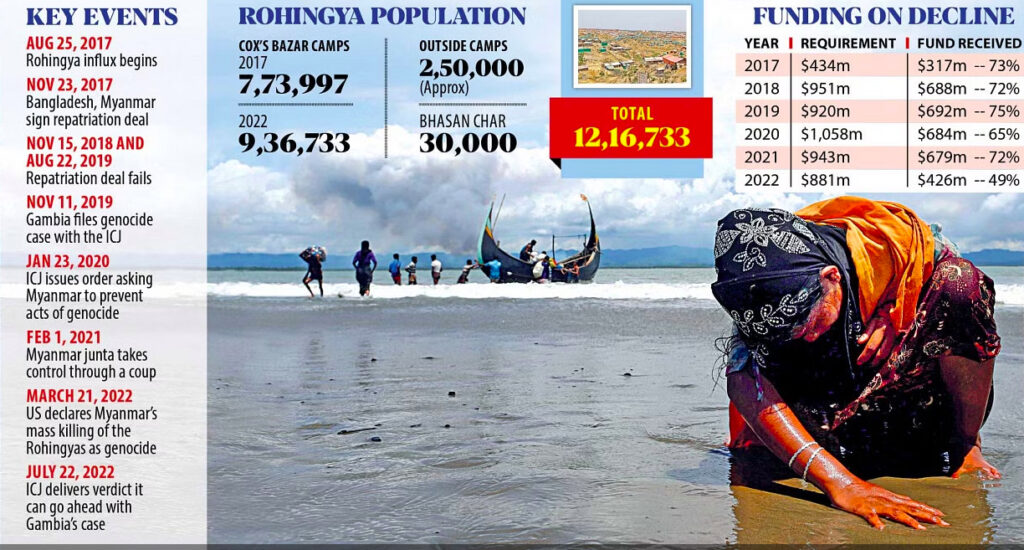

In the camps set up in the Cox’s Bazar area, Bangladesh hosts 918,841 million[3] Rohingya refugees, which includes over 740,000, who have arrived from Myanmar since 2017. On Dhaka’s part, it isn’t a voluntary acceptance of the refugees, but one that could not be avoided. The numbers of these men, women, and children who left after a genocidal campaign undertaken and sponsored by the Myanmarese army personnel, are staggering for a developing country like Bangladesh.

External humanitarian assistance has been and continues to be provided by 136 partners including the US, UK, Australia, and the European Union through 10 UN agencies, 52 International NGOs, and 74 Bangladesh NGOs. In September 2022, the US announced more than $170 million in additional humanitarian assistance for Rohingya inside and outside Myanmar, as well as for host communities in Bangladesh. With this new funding, total US assistance in response to the Rohingya refugee crisis reached nearly $1.9 billion since August 2017.[4] However, even this funding is proving to be insufficient. The Human Rights Watch (HRW) has noted that the 2022 Joint Response Plan for the Rohingya Humanitarian Crisis (JRPRHC) of the UNHCR[5]received less than half of the US$881 million needed for the year. This lack of adequate assistance may have enormously burdened the Bangladesh economy. The JRPRHC duly notes, “Bangladesh has borne an enormous responsibility and burden, including financially, for this crisis”[6]. According to a 2019 estimate, Dhaka has to spend $1.21 billion a year for supporting the Rohingyas.[7] Over the years, as a result of population growth, inflation, and a decline in foreign funding, the cost would have certainly gone up.

Although the first strategic objective outlined in the JRPRHC is to ‘work towards sustainable repatriation of the Rohingya refugees and Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals (FDMNs) to Myanmar’, due to a lack of progress in repatriating the refugees to Myanmar, the assistance programme has remained all about attending to the bare necessities of the refugees/FDMNs and the host communities. These include: “strengthening the protection of Rohingya refugee/FDMN women, men, girls, and boys; delivering life-saving assistance to populations in need; fostering the well-being of host communities in Ukhiya and Teknaf sub-districts of Bangladesh; and strengthening disaster risk management and combat the effects of climate change.”[8]

In spite of several frantic efforts by the Bangladeshi government, neither the Myanmar government has shown much interest in taking the refugees, nor has the latter expressed any desire to return to their homeland, especially due to the prevailing hostile environment in the Rakhine state. The state of affair in Bangladesh, however, isn’t ideal either, being marked by a range of restrictions that prevents the Refugees from seeking formal employment and accessing Bangladeshi educational or health facilities. In short, life in the refugee camps is akin to being confined to the congested facilities in the Cox’s Bazar area, grappling with extreme poverty, unsanitary living conditions, and long-term health issues, which have been only worsened by the pandemic.

Some able-bodied refugees do get to work informally, providing cheap labour to the local population in Ukhiya and Teknaf. However, charges that they are ‘taking away the opportunities that belong to the Bangladeshis’ are widely prevalent. Some others have set up small shops within the perimeters of the camp, selling essential items to the inmates. Madrassas and other informal education centres have come up too, although these by no means are adequate to cater to the educational needs of the children. Stories regarding rampant drugs, crime, and extremism inside the camps have periodically been published in the local newspapers. In April 2022, two Rohingya youth, aged 15 and 14 respectively, were arrested with 6000 Yaba pills near the capital Dhaka’s Hazrat Shahjalal International Airport.[9] Armed criminal gangs have been formed inside the camps that indulge in a range of activities including human trafficking and murder of Rohingya activists. For obvious reasons, Rohingya continue to evoke feelings of sympathy and apprehension simultaneously.

The attitude of the Bangladeshi security services hasn’t helped either. The Armed Police Battalion (APBn) of Bangladesh took over security in the Rohingya camps in July 2020. From time to time, they have carried out operations to control criminal activity inside the camps. In October 2022, the APBn carried out ‘Operation Root Out’ and arrested 56 Rohingya including 24 people involved in the murder of seven majhis (Rohingya community leaders).[10] Another 19 refugees were arrested the same month for their alleged involvement in ‘multiple cases of robbery, weapons and murder’[11]. A total of 900 Rohingya have been arrested on various charges since mid-2022.[12]

On the other hand, the HRW, in January 2023, published a report detailing how the APBn is engaged in “rampant” extortion, harassment, and wrongful arrests of refugees.[13] The report, among other things, cited how the APBn personnel has been planting drugs on the refugees in order to extort money from them. The money demanded ranged from 10,000-40,000 taka (US$100-400) to avoid being arrested to 50,000-100,000 taka ($500-1,000) for the release of a detained family member. The APBn has dismissed these allegations as ‘fabricated’[14]. Notwithstanding such denial, there is no denying the fact that the lives of the refugees in the camps remain miserable. Since 2021, about 20,000 Rohingya have been relocated by Bangladeshi authorities to the tiny island of Bhasan Char, where facilities are reportedly far better than the camps.[15] The HRW, which termed it ‘An Island Jail in the Middle of the Sea’[16], however, says refugees face “severe movement restrictions, food shortages, abuse by security forces, and inadequate education, health care, and livelihood opportunities.”[17]

Onward Malaysia

Rohingyas are seeking escape from the squalid conditions prevalent in the camps. While only a small percentage of the total number of refugees have attempted to travel by air by using fake passports[18], the majority of them have taken to the sea to reach Malaysia. According to UNHCR, close to 2000 refugees managed to crossover from the camps in Bangladesh in 2022. More than two-thirds of the passengers were women and children. This, however, isn’t surprising given the demography of the refugee camps. According to the UNHCR, of the 918841 refugees, a staggering 481765 (52.4 percent) are children below the age of 18 years. Of these 234744 are girls and 247021 are boys. Only 32870 are older persons above the age of 59 years, while 404206 are adults between 18 and 59 years.[19] Only the able-bodied were to escape the ‘ethnic cleansing’ in Myanmar. The same is being repeated in the context of perilous sea journeys.

For some of the refugees, the choice of Malaysia is somewhat natural. For decades, Rohingya men from Myanmar have travelled illegally to Malaysia taking advantage of that country’s policy of welcoming Muslims from around the world. Over 100,000 Rohingya Muslims are officially registered as refugees with the UNHCR in Malaysia.[20] Although conditions there aren’t the most ideal, most of them manage to find jobs or alternately attempt their hands in becoming street hawkers. Compared to the hopeless condition back home, Malaysia provides hope for a better life. These Rohingya men had their wives and children back in Myanmar until the 2017 violence. It is mostly these women and children, who were forced to relocate to Bangladesh, who have constituted a majority of the people who have taken to the sea to reach their husbands, parents, or family members in Malaysia.

Given the fairly long history of illegal sea travel, human trafficking gangs from Myanmar, Thailand, and Bangladesh have proliferated in the region to take advantage of the lucrative trade. Similar to the Rohingya, thousands of Bangladeshis over decades have travelled to Malaysia legally as well as illegally in search of work. With numbers ranging from 250,000[21] to 300,000, they constitute the third largest legal migrants in that country. A similar number are estimated[22] to have entered the country illegally.

Modus Operandi

Past incidents have revealed the following modus operandi. At least two to three boats leave for Malaysia every month from Bangladesh’s coast. The criminal gangs within the refugee camps aligned with the traffickers contact potential travelers. Fees are collected or on a few occasions are kept on deferred mode to be paid by their relatives on arrival in Malaysia. On the appointed day, small boats ferry the refugees to the high sea where they are transferred into larger rickety wooden boats or fishing trawlers, mostly unfit for sea travel. Each of these larger boats is packed with as many persons as possible. Food on board is kept limited to accommodate more passengers. The boats, with the crew armed with a satellite phone, sail on a journey that could last nearly a month before it hopes to reach Malaysia. After about ten days, the passengers run out of food and water and start falling sick. Those who die on board are dumped into the sea.

By the time, these boats reach closer to Malaysian waters, contact is made with the relatives of the passengers who have not made their payment. They are threatened to make the payment quickly. There have been instances when payments were collected from the relatives of dead passengers. The mode of such deferred payment is hybrid, made either electronically or by agents operating in Malaysia. Once the payments are collected, the boats sail towards the coast in the dead of the night. This, however, is the narrative of a successful landing. There have been occasions when boats have sunk within hours of their journey[23], drowning some or most of the travellers.

Malaysia’s refugee policy has changed in recent years, amid concerns, fueled by social media, of potential Covid-19 infections brought in by the refugees.[24] It monitors its waters much more efficiently and refuses entry to let any unauthorized vessel. This may or may not be known to the refugees. But the traffickers assure them safe travel and landing in Malaysia, taking them instead to some of the Indonesian islands, or simply abandoning them in the high sea, after boats malfunction.

The UNHCR had termed 2020 as the deadliest year for refugee journeys across the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea. It was that year that the agency began monitoring casualties in the region and reported more than 200 people dead or missing. The year 2021 and 2022 have been worse. Nearly 400 refugees perished in the sea in 2022. The desperation of the hapless refugees is feeding the greed and criminality of the organised criminal gangs when the majority of the world chooses to look away.

The Future Pathway

Close to 2000 refugees managed to crossover from the camps in Bangladesh in 2022, six times more than in 2020. Due to the peculiar circumstances and push factors, such perilous journeys are bound to continue well into 2023 and beyond. In the last week of December 2022, the UN special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, Tom Andrews, urged governments in south and south-east Asia to act on the calls of distress from the Rohingya refugee boats. However, there is little hope that each distress call would be responded to and each sinking boat would be rescued.

The alarming episodes of death of the Rohingya either by starvation or drowning in the sea, however, must not divert the world’s attention from the very reason that result in such perilous journeys. Two priorities must never be lost sight of. First, the Rohingya would have to be repatriated with dignity to the country of their origin, i.e. Myanmar. That seems unlikely given the prevalent chaos in that country. Second, till that happens, the condition of the refugees in the camps must be substantially improved. While committed funding must be made available on a regular basis, their effective utilization must assume priority. Bangladesh must be lauded for hosting more than a million refugees since 2017, however, it cannot shun its responsibility from protecting them from its own security forces. The camps need to be managed better, with every effort made to fulfill the desires of the refugees to live with dignity.

END NOTES

[1] “About 180 Rohingya refugees feared dead after boat goes missing”, The Guardian, 27 December 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/dec/26/very-weak-rohingya-refugees-land-on-indonesia-beach-after-weeks-at-sea.

[2] “Vietnam vessel saves 154 Rohingya from sinking boat, transfers to Myanmar navy”, The Hindu, 9 December 2022, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/vietnam-vessel-saves-154-rohingya-from-sinking-boat-transfers-to-myanmar-navy/article66243645.ece.

[3] Data in January 2022, UNHCR.

[4] US Department of State, Press Statement, “United States Announces More Than $170 Million in Humanitarian Assistance for the Rakhine State/Rohingya Refugee Crisis”, 22 September 2022, https://www.state.gov/united-states-announces-more-than-170-million-in-humanitarian-assistance-for-the-rakhine-state-rohingya-refugee-crisis/

[5] UNHCR, 2022 Joint Response Plan Rohingya Humanitarian Crisis, https://reporting.unhcr.org/2022-jrp-rohingya.

[6] Ibid. p.13.

[7] “Cost of Supporting Rohingyas: Dhaka now saddled with $1.2b a year”, The Daily Star, 25 September 2019, https://www.thedailystar.net/frontpage/cost-supporting-rohingyas-dhaka-now-saddled-12b-year-1804855.

[8] UNHCR, 2022 Joint Response Plan Rohingya Humanitarian Crisis, op.cit.

[9] “2 Rohingya teenagers arrested with Yaba tablets near Dhaka airport”, Business Insider Bangladesh, 5 April 2022, https://www.businessinsiderbd.com/national/news/20163/2-rohingya-arrested-with-yaba-tablets-at-dhaka-airport.

[10] “Bangladesh crackdown in Rohingya camps after murders”, Mizzima, 31 October 2022, https://mizzima.com/article/bangladesh-crackdown-rohingya-camps-after-murders.

[11] “19 Rohingyas arrested from Cox’s Bazar camps”, Dhaka Tribune, 31 October 2022, https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/2022/10/31/19-rohingyas-arrested-from-coxs-bazar-camps.

[12] “APBn extorts Rohingyas in camps: HRW”, New Age Bangladesh, 18 January 2022, https://www.newagebd.net/article/191914/apbn-extorts-rohingyas-in-camps-hrw.

[13] Bangladesh: Rampant Police Abuse of Rohingya Refugees, Human Rights Watch, 17 January 2023, https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/01/17/bangladesh-rampant-police-abuse-rohingya-refugees.

[14] “APBn extorts Rohingyas in camps: HRW”,op.cit.

[15] Mohammad Al-Masum Molla, “Bhasan Char: Better conditions, but home still beckons”, Daily Star, 25 August 2022, https://www.thedailystar.net/rohingya-influx/news/bhasan-char-better-conditions-home-still-beckons-3102681.

[16] Human Rights Watch, “An Island Jail in the Middle of the Sea”, 7 June 2021, https://www.hrw.org/report/2021/06/07/island-jail-middle-sea/bangladeshs-relocation-rohingya-refugees-bhasan-char.

[17] Erin Cunningham, “Refugee rescue off Indonesian coast highlights plight of Rohingya minority”, Washington Post, 31 December 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2021/12/31/rohingya-refugees-indonesia/.

[18] Multiple reports include the following. “2 Rohingya women held at Dhaka airport”, Daily Star, 26 May 2019, https://www.thedailystar.net/backpage/news/2-rohingya-women-held-dhaka-airport-1748902.

[19] UNHCR, 2022 Joint Response Plan Rohingya Humanitarian Crisis, op.cit., p.11.

[20] “‘Left to die’: Fates of 5 Rohingya boats across Asia spotlight enduring crisis of stateless Muslim minority”, South China Morning Post, 1 January 2023, https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/people/article/3205108/left-die-fates-5-rohingya-boats-across-asia-spotlight-enduring-crisis-stateless-muslim-minority.

[21] “In Malaysia: Bangladeshis are 3rd largest legal migrants”, Daily Star, 11 November 2016, https://www.thedailystar.net/backpage/malaysia-bangladeshis-are-3rd-largest-legal-migrants-1312927.

[22] “Bangladeshis and Indonesians in Malaysia”, Migration News, vol.1, no.6, July 1994, https://migration.ucdavis.edu/mn/more.php?id=377.

[23] “At least three women die after Rohingya boat sinks off Bangladesh”, Al Jazeera, 4 October 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/10/4/at-least-three-women-die-after-rohingya-boat-sinks-off-bangladesh

[24] Tashny Sukumaran, “As Malaysia battles the coronavirus, its Rohingya refugees face a torrent of hate”, South China Morning Post, 28 April 2020, https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/politics/article/3081958/malaysia-battles-coronavirus-its-rohingya-refugees-face-torrent?module=hard_link&pgtype=article.

(Bibhu Prasad Routray is Director of MISS. This Special Report is published as part of Mantraya’s ongoing “Fragility, Conflict and Peace Building” projects. Mantraya Special Reports are peer-reviewed publications.)