MANTRAYA SPECIAL REPORT#03: 27 JANUARY 2016

BOH ZE KAI

Abstract

Once a remote, uncontrollable region, Shan State in North Myanmar is home to the ‘Wild’ Wa people, who make up 10percent of its population. Nonetheless, with 30,000 active soldiers, the United Wa State Army (UWSA), is prima inter pares in the narcotics production zone of the Golden Triangle and one of the largest rebel armies in the world. Part of the UWSA’s success can be attributed to their skilful diplomacy with state and regional actors, capitalising on connections gained from their time in the Communist Party of Burma (CPB) to build vital trade and military alliances. In light of political change in the 2015 Myanmar Elections, this article aims to explore ‘foreign’ policy options for the UWSA with the Myanmar Government, the Chinese Government, narcotics groups in Thailand and rebel groups in the Shan State.

Introduction

In 1968, under pressure from the government, the Communist Party of Burma (CPB) retreated northwards from Central Myanmar to the Shan State, a mountainous region bordering China. In the subsequent years, bolstered by Chinese economic and military support, the CPB consolidated its position, drew its strength from mountain minorities like the Wa and Kokang, and established itself as the kingpin of the Golden Triangle. In 1989, the CPB fractured into smaller groups like the National Democratic Alliance Army (NDAA) and the United Wa State Army (UWSA). These groups morphed into opium cultivation and heroin manufacturing powerhouses, and by the 2000s the UWSA had become the world’s largest narcotics distributor. Today, the UWSA’s methamphetamine-based narcotics industry is concentrated in factories to its southern exclave (see Figure 1) with a particular emphasis on manufacturing yaba, a caffeine-methamphetamine mixture party drug consumed almost exclusively in Southeast Asia. Drug money has fuelled a narco-military force comparable to the Myanmar Army, the Tatmadaw. The foreign relations of the UWSA are hence dominated by its ideological goals of autonomy and its reliance on narcotics production and distribution.

Figure 1: Map of Shan State with Key Areas of Influence and Trade Routes (Prepared by the author), Red: Main amphetamine distribution routes. Amphetamine labs are concentrated in the southern territory of UWSA. Purple: Ancillary trade and arms smuggling routes used by the UWSA

Relations with Myanmar Government

Peace negotiations lasting over several months saw eight of the fifteen key rebel groups signing the government-led Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) in October 2015. A mere trust-building mechanism with broad guidelines on discussions towards a federal state, the NCA is not a comprehensive ceasefire or conflict resolution agreement. While unlikely to achieve peace on its own, it represents a platform for dialogue and a key milestone on the peace process. The notable refusal of the UWSA and other allied large factions to sign the NCA signifies a deep distrust between state and factional actors. In November 2015, the UWSA hosted the a summit at Pangkham, the Shan state’s de facto capital, for factions not party to the NCA. A joint statement expressed solidarity in fighting for an amended constitution, and a commitment to dialogue with the newly elected government[1] with the mutually stated goal of national reconciliation.

Results of the 2015 parliamentary elections has placed power in civilian hands in Myanmar. And this is likely to radically impact the nature of relations between UWSA and the government. The National League of Democracy (NLD) which ran on a platform of peace and national reconciliation, provides an opportunity to nationalist groups to fight for further federalism. The NLD has promised a federal union for ethnic minorities in its election manifesto, while remaining silent on details regarding such a structure. The NLD will probably focus initially on consolidating their power in Myanmarese heartlands. Assigning more autonomy to the restive border regions at least temporarily will relieve government liability during the embittered process of taking over political authority from entrenched institutions.

The Tatmadaw’s insistence that groups adhere to a six-point principle institutionalising the role of the military in political decisions makes assimilation a bitter pill for rebels. Decades of conflict have bred mistrust and enmity between rebel groups and the military and the constitution essentially allows the Tatmadaw to act without civilian oversight. With a quarter of the seats in both the upper and lower house, the Tatmadaw still holds great political authority in Myanmar, employing the implicit threat of a coup d’etat. Dismantling the monolithic grip of the military over Myanmar will be high on the NLD’s agenda, and co-opting rebel militant groups could help restrain its impunity. It is likely that the UWSA will cooperate with any agenda that involves weakening the military, and are natural allies to the NLD’s cause. Nonetheless, while an opportunity to grow at the expense of the Tatmadaw, the UWSA must take care not to fall prey to a ‘divide-and-conquer’ tactic. Expending strength and resources unnecessarily against the Tatmadaw will strengthen the NLD, who may then crush both their power rivals at once.

However, the narcotics trade remains a significant obstacle to UWSA and NLD relations. International entities see the NLD government as a more cooperative partner for drug eradication programmes compared to the USDP and are likely to increase pressure on the government to combat the narcotic barons. Clamping down on the narcotics trade will trigger heated opposition from all rebel groups who use it to fund their operations. Ultimately, strangling narcotics production is contingent on the availability of alternative sources of revenue. UNODC’s efforts in conjunction with foreign state donors to promote coffee, macademia and rice agriculture such as RASC25 in the Wa Region[2], have not made much of an impact in the region. However, regime change may make this option finally viable. A well-executed eradication campaign hence rests on tripartite cooperation between rebel groups to enforce policies, the government to provide frameworks, and international polities to back it with funding and expertise. At the end of the day, despite ideological inclinations, the NLD has shown itself to be a pragmatic political actor when required. The illusion of commitment to combating the narcotics trade is enough for the NLD to relieve international pressure while allowing narco-armies to counterbalance their political rivals in the Tatmadaw until genuine national reconciliation can be achieved.

In the short- to medium- term, the UWSA should leverage on the challenges of the NLD to achieve semi-legal status and expand for the mutually beneficial objectives of combating the military and building a federal union. However, in the long-term, Wa authorities should recognise that disarmament and legitimacy is the best way to achieve sustainable development for their people. Of course, convincing Wa leaders to give up their narcotic gold mine will likely be an uphill struggle.

Relations with China

UWSA’s relations with China are essentially a continuation of the CPB era, when shared ideologies resulted in close military and economic support. Today, Sino-Wa relations are based on shared ideas of mutual security, economic growth and cultural soft power. Chinese investment has been a key driver of economic growth in licit industries and infrastructure in Wa territory. Guangdong-based investors received a UWSA-backed monopoly over Pangkham’s thriving casino[3] while the logging industry and infrastructure development across UWSA territory is supported primarily by Yunnan-based construction companies. China has been providing agricultural funding and expertise to develop 200,000 hectares[4] of substitute crops for opium with a focus on tea, rubber and macademia; almost all of which are exported to China. Large corporations like the Yucheng Group have also been courted for an undisclosed amount of commercial and structural investment. The UWSA has few other sources of investment, and the China’s continued support is critical for non-narcotic growth.

Chinese technological transfer has provided alternative revenue sources. Considering the fact that the large swathe from India to Thailand is replete with armed movements, small arms trade has become a vital industry for the Wa. Chinese factories across the border supply production technology for Type 56 rifles, RPD LMGs and even PMN-type antipersonnel mines. However, factories in the Wa state are capable of producing armaments independently. The scale of production is unknown, but UWSA arms have been found in militant caches from Nagaland to Pattani. A Chinese crackdown in 2008 has also seen Chinese producers move factories of counterfeit consumer products like DVDs and clothing into Mong La[5] (see Figure 1). These illicit industries, while destabilising to region, pose little threat to China and represent a powerful source of revenue without harming cross-border relations.

China’s war on the drugs focuses heavily on heroin, which was trafficked through Wa territory. Under Chinese pressure, the UWSA declared its territories an opium-free zone in 2005. Despite a four percent increase in opium production from 2013 to 2014[6], this has caused the Golden Triangle’s share of the global opiate market to drop to 15 percent in 2014 from 70 percent in 1990[7]. To compensate, the UWSA transformed its southern jungle border with Thailand into a massive methamphetamine factory, dotting the region with labs producing yaba for export to Thailand through the border town of Tachileik and to a lesser extent, crystal meth to China. Opiate consumption as a share of all drug abuse in China has since dropped from 90 percent in 2001 to 50 percent in 2008[8] but amphetamine consumption has risen to compensate for this. Ironically, 90 percent of meth[9] in China today purportedly comes from Myanmar, suggesting that China has merely traded one drug problem for another.

To avoid jeopardising growing friendships with the Myanmarese government, Chinese political and military support has been overt but deniable. Chinese diplomatic representatives attended UWSA ceremonies in 2009[10], and UWSA high officials continue to request for China to mediate peace negotiations[11]. Alongside small arms, UWSA purportedly own sophisticated materiel such as Chinese Type 96 howitzers, armoured fighting vehicles[12] and even Mil Mi-17 attack helicopters. Acquisition of such heavy equipment implies Ministry of State Security complicity rather than small-scale arms dealing networks.

Funding the UWSA’s various projects necessitates maintaining the methamphetamine trade, as no other source of revenue is likely to be large enough in the long term. However, the continued trend of meth abuse in China is likely to be viewed as a social and security threat in the medium- to long-term. China may be willing to tolerate the UWSA in the short term. Myanmar is a critical link on China’s ambitious ‘One Road-One Belt’ policy, and if trends persist, official relations may outweigh the interests of border ethnic groups. Hence, over time, the UWSA must find a way to shut off narcotic flows towards China to avoid angering their big brother to the North. Instead, the UWSA could pursue flows towards India, where average tablet retail prices of US$12 remain high compared to US$5 in Thailand[13]. These are medium-term solutions at best, and continued Chinese investment is essential to the long-term goal of reversing economic dependence on narcotics.

Relations with Thai Narcotics Groups

Thailand is the largest market for the UWSA’s primarily yaba based narcotics industry. At the same time, it also supplies the chemical inputs. In 2012, the Department of Special Investigations discovered forged air cargo manifests for two billion cold tablets. The main input, pseudoephedrine, is obtained from cold tablets smuggled through Bangkok from Taiwan and South Korea. Yaba has become an entrenched social phenomenon, cutting across social groups from menial labourers to investment bankers, while yaba trafficking in Thailand has become a US$30billion industry[14] of which an estimated 75 percent comes from Myanmar. Typically, pills are smuggled into eastwards into Laos and then southwards into Northern Thailand.(see Figure 1) Thai authorities see the UWSA as a menace to be eradicated, not a legitimate entity to be negotiated with. As both consumer and supplier, the UWSA must counteract Thai eradication policies while strengthening ties to Thai drug barons.

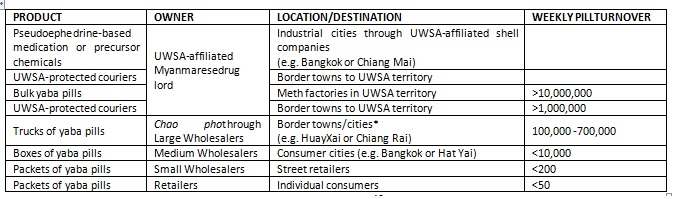

A complex chain of intermediaries links Myanmarese drugs with Thai consumers (see Figure 2). However, UWSA influence is mostly limited to production and trafficking to ethnic Chinese large wholesalers or chao pho, who act as Godfather-figures in a geographically exclusive multi-tier distribution channels that see drugs change hands an average of seven times[15] before reaching consumers. This uneasy peace allows Bangkok to overlook the persecution of these chao pho who command high status and respect in their communities. In 2003, an empassioned War on Drugs by then Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra terrorised low-level drug wholesalers and retailers, but left the chao pho and their structures relatively intact. A chief reason is that the chao phoexercise degrees of control over the law enforcement agencies through their extensive networks of political patronage and nakleng underlings which coerce law enforcement and government at every level, placing them effectively above the law[16].

Table 2: Drug Trafficking Process from Myanmar to Thailand[17]

In 2009, Thailand resurrected Task Force 399, now renamed the 151st Special Warfare Company, a controversial elite anti-narcotic police force previously shut down due to concerns over its extrajudicial tactics and disregard for international boundaries[18]. In 2015, the Office of Narcotics Control Board (ONCB) launched the Safe Mekong Coordination Centre, which has seized 30 tonnes of precursor chemicals, rather than focussing solely on the finished product[19]. While the overall impact on the drug trade remains miniscule, redirecting the oppression and interception of drug trafficking higher on the production chain represents an unprecedented threat towards the UWSA and its operations. In anticipation, the UWSA should begin to diversify its sources of precursor chemicals even at a higher cost. A bolder step would be to move away from pseudoephedrine-based production techniques, and diversify towards phenylacetone-based methamphetamine production. While phenylacetic acid is used in 78 percent of all meth production worldwide[20], in 2013, only 95 kilograms were seized in Myanmar compared to 6.5 tons in China. With authorities concentrating on crushing pseudoephedrine, it is likely phenylacetone-based production will be overlooked for now.

As an indicator of consumption rates, the quantity of methamphetamine pills seized has increased tenfold from 25 million in 2008 to 250 million in 2013[21]. In the face of rising consumption patterns,chao pho rarely engage in turf conflict, choosing instead to compete over new consumers. Nonetheless, the UWSA’s fear of internecine strife between the chao pho may well become a reality once the market becomes saturated. War between the chao pho would disrupt logistics and transportation networks, draw attention to the yaba trade and result in large-scale police crackdowns.

Conflict is an inherent risk to the drug trade, but the UWSA can take measures to restrain and control involved parties. One method that seems to have results is providing a scapegoat in the form of transnational criminal organisations, which gives the government enough positive press to lay off the local and regional actors. An entire special task force has been mobilised in 2015 with the sole intent of targeting foreign criminal gangs[22]and the high profile arrests of American kingpin Joseph Hunt in 2013 and British drug dealer Micheal France in 2014 are contrasted to a conspicuous absence of high-profile Thai crime barons persecuted. The UWSA should pressure the chaopho to support the use of foreign gangs as a distraction through the judicial application of their patronage systems in order to prevent the encroachment of the narcotics trade. However, in the medium-term, the UWSA should aim to integrate itself into a legal political framework under the NLD where it can find internationally recognised refuge and backing for legitimate economic activities.

Relations with other rebel groups in Shan State

Figure 3: Factional Map of Rebel Areas of Influence and Military Garrisons in Shan State (Prepared by the author), Tatmadaw: North-Eastern Command (Lashio) – 30x Battalions; Eastern Command (Taunggyi) – 42x Battalions; Triangle Region Command (Kengtung) – 23x Battalions; Eastern Central Command(Kho Lam) – unknown; Laukkai Regional Operations Command and Wanhseng Regional Operations Command – 8x Battalions

The staunchest allies of the UWSA are its erstwhile CPB comrades (see Introduction): the National Democratic Alliance Army (NDAA) in Mongla and the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) in Kokang as well as the Shan State Army-North (SSA-N) based in Wan Hai. The network of alliances preserves the validity and efficacy of trade routes across Shan State, enabling the profitable trade in narcotics, jade, timber and rare minerals. Nonetheless, alliances and enmities are fluid and subject to shifting priorities, with self-preservation as the main priority.

‘Alliance’ indicates economic and political solidarity rather than mutual defence. The MNDAA was crushed by the Tatmadaw once in 2009 and most decisively in June 2015, resulting in the loss of the Kokang region (see Figure 3)to the North. In October 2015, the Tatmadaw launched an ongoing offensive against Wan Hai, committing heavy weaponry and large numbers[23]. The UWSA has remained passive in the face of attacks on its allies, likely because they do not represent a large enough strategic threat to its existence or operations. Further, aggrandising disagreements with the Tatmadaw and jeopardising the ceasefire after a hard-earned peace deal in 2013 would be a disproportionate sacrifice for the preservation of allies in peripheral territories.

Acknowledging this, the Tatmadaw appears to be engaging in a manner of salami tactics by steadily enveloping the UWSA. Alongside attacks on buffer states and allies, the Tatmadaw has also strengthened military strength throughout the Shan State. In 2011, the Eastern Central Regional Military Command (ECC) was established at a strategic location at Kho Lam blocking UWSA access to the Middle Shan State, the ECC has since engaged in clashes with the SSA-N to secure the west of the UWSA. In addition, the Wanhseng Regional Operations Command was formed in 2011 along the route between Mongla and Tachilek. The build-up of military strength throughout the Shan State is designed to divide the different groups and control important routes. The UWSA is right to stay out of conflict with the Tatmadaw, but should the Tatmadaw be allowed to advance unchecked, the UWSA may soon find itself under siege.

In contrast, the UWSA strongly contested government efforts in 2008 to reclaim control over the town of Mong Pawk in order to maintain its connection to the NDAA inMongla.[24] The NDAA’s prime location makes it strategically critical for the continued survival of the UWSA.If the Tatmadaw manages to gain control of the Mongla region, it would cut off the manufacturing hub in southern half of the Wa state from the administration in Pangkham, while simultaneouslystrangling and denying trade routes leading to Laos and Thailand, shutting down financing and ultimately present an existential threat to the UWSA. In order to avoid a similar situation to the MNDAA, arming and fortifying the small3,000 strong army of the NDAA will be a priority for the UWSA. At the same time, the Mongla region has been a powerhouse for economic growth with the construction of the Mongla hydropower dam, retail and tourism centres and large-scale agricultural expansion[25]. A seminar held in August 2015[26] discussed the opening of the Thai border with southern UWSA territory towards Mong Ton to businessmen, indicating a desire to rejuvenate cross-border trade.Furthering legitimate economic links at an administrative level would create a viable economic region along the Thai-Chinese-Laotian-Myanmarese border centred on both licit trade, making national reconciliation a financially viable option.

The Shan State Army-South (SSA-S) has been a rival of the UWSA since 2006,[27]when combined UWSA-Tatmadaw operations resulted in weakened SSA-S influence over South Shan. Since then, low-level conflicts and confrontations have persisted, including a 2012 siege of an SSA-S camp by UWSA in Eastern Shan[28]. On 15 October 2015, the SSA-S was one of eight signatories to the NCA[29], effectively dividing Shan groups into two separate camps. The division should not be overstated as neither are hostile to each other nor is the NCA a binding alliance with the Tatmadaw, but the two factions essentially represent diverging strategies of relations with the government. The size and influence of the UWSA allows it to engage in direct negotiations with the government, and in fact, disadvantages it in group consensus. However, as one of the largest and best equipped among the signatories the relatively small SSA-S can essentially command the combined political will and bargaining power of the eight groups. In order to prevent the Tatmadaw from turning the groups against each other, the UWSA must work to normalise relations with the SSA-S. Talks held in Dec 2012 focussed on opium harvest replacement[30], but negotiations focussing on core issues relating to political, economic or military cooperation will build trust and pave the way for a more united front with regards to achieving autonomy and federation.

The rise of the NLD and their emphasis on national reconciliation makes unity among the rebel groups of the Shan State increasingly important. United, the groups can pursue a wider stance and greater degrees of autonomy for all parties. It is in the interest of the government to fragment the various factions in order to limit the bargaining power of each one. As the largest, richest and most influential faction, the UWSA should work to assume effective leadership over the region in order to maximise political gain in the impending reconciliation process.

Conclusion

The mainstay of any UWSA strategy focusses on preserving economic strength by maintaining the narcotics trade in order to campaign for political autonomy. In the past, the narco-army was capable of holding back government-led offensives, capitalising on the general state of anarchy in the Shan State to drive the isolated government into a stalemate. However, as its relations with the rest of the world improve, the government in Myanmar will grow stronger and the rise of the NLD would propel the country into the mainstream international community. In light of this, the UWSA risks becoming irrelevant, and devolving into a criminal gang will cause it lose backing in Beijing, rendering it an easy target for annihilation by Thai, Chinese and Myanmarese authorities. Sustaining political capital will rely on maintain economic relevance through links to China and the drug trade in Thailand and political relevance through links to rebel groups and a superior military. A superior strategy would be to pursue legitimate economic and political interests, integrate into the legitimate political society and bargain for autonomy for the Wa people while its political capital runs strong.

End Notes

[1]Shan Herald Agency for News (2015)

[2]UNODC (2009)

[3]Ling, Xiao (2005)

[4] National Narcotics Control Commission (2014)

[5]United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2014)

[6]United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2014)

[7]United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2014)

[8]Zhang, Sheldon and Chin, Ko-lin (2014)

[9]United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2013)

[10]Dinger, Larry (2010)

[11]Weng, Lawi (2015)

[12]Davis, Anthony (2015)

[13]United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2015)

[14]United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2015)

[15]Treerat, Nualnoi (2000)

* Consensus is divided as to whether or not the drugs are exchanged at the border or in Bangkok. It is likely both types of exchanges are taking place at the same time.

[16]Fabre (2002)

[17]Lintner, Bertil and Black, Micheal (2009) and Chouvy, Pierre-Arnoud et Meissonier, Joel (2002)

[18]Asia Times (2009)

[19]Chiangrai Times (2015)

[20]International Narcotics Control Board (2014)

[21]United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2015)

[22]Bangkok Post (2015)

[23]Radio Free Asia (2015)

[24]Shan Herald Agency for News (2012)

[25]The Irrawady (2015)

[26]Shan Herald Agency for News (2015)

[27]The Irrawady (2006)

[28]Myanmar Peace Monitor (2014)

[29]Restoration Council of the Shan States (2015)

[30]Myanmar Peace Monitor (2014)

]REFERENCES

Asia Times. 4 November 2009. Drugs, guns and war in Myanmar. Retrieved from http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Southeast_Asia/KK04Ae02.html. Retrieved on 28 Nov 2015.

Bangkok Post. 4 January 2015. Police target international crime gangs. Retrieved from http://www.bangkokpost.com/archive/police-target-international-crime-gangs/454182. Retrieved on 28 Nov 2015.

Chiangrai Times. Safe Mekong Drug Suppression Operations to be Extended. Retrieved from http://www.chiangraitimes.com/safe-mekong-drug-suppression-operations-to-be-extended.html. Retrieved on28 November 2015.

ChinaNews. 26 May 2015. Yucheng Group Offers Investments to Myanmar’s Wa Group in Support of “One Belt One Road”. Retrieved from http://www.chinanews.com/fortune/2015/05-26/7301519.shtml. Retrieved on 15 Nov 2015.

Chouvy, Pierre-Arnoud and Meissonier, Joel. October 2002. Yaa Baa: Production, traffic et consummation de methamphetamine enAsie du Sud-Est continentale. Bangkok: L’Institut de recherché sur l’Asie du Sud-Est contemporaine (IRASEC). Retrieved on 11 Dec 2015. Source is written in French.

Davis, Anthony. 22 July 2015. Wa army fielding new Chinese artillery, ATGMs. IHS Jane’s Defence Weekly. Retrieved on 8 Nov 2015.

Dinger, Larry. 22 October 2009. Burma: Wa Army Still Opposes Border Guard Force.Wikileaks: Wikileaks cable: 10RANGOON57_a. Retrieved on 8 Nov 2015.

Dinger, Larry. 29 January 2010. Burma: A Heart to Heart with the Wa.Wikileaks: Wikileaks cable: 09RANGOON704_a. Retrieved on 8 Nov 2015.

Fabre, Guilhem. 30 November 2002. Criminal Prosperity: Drug Trafficking, Money Laundering and Financial Crisis after the Cold War. London: Routledge. Retrieved on 28 Nov 2015.

International Narcotics Control Board. 2014. Precursors and chemicals frequently used in the illicit manufacture of narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances. New York: INCB Precursor Annual Report. Retrieved from https://www.incb.org/documents/PRECURSORS/TECHNICAL_REPORTS/2014/PARTITION/ENGLISH/2014PreAR_E-ExtentOfLicitTradeInPrecursors.pdf. Retrieved on 28 Nov 2015.

Ling, Xiao. 5 August 2005. Pangkham Casino Pays 8 Million a Year in Taxes to Wa Government. QQ News. Retrieved from http://news.qq.com/a/20050508/001799.htm. Retrieved on 15 Nov 2015. Source written in Chinese.

Lintner, Bertil and Black, Micheal. 4 March 2009. Merchants of Madnesss: The Methamphetamine Explosion in the Golden Triangle. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Press. Retrieved on 11 Dec 2015.

Myanmar Peace Monitor. May 2014. Restoration Council of Shan State/Shan State Army. Burmese News International. Retrieved from http://www.mmpeacemonitor.org/research/monitoring-archive/168-ssa-s. Retrieved on 08 Dec 2015.

National Narcotics Control Commission. 2014. Annual Report on Drug Control in China. Beijing: National Narcotics Control Commission, 2014. Retrieved from http://blog.sina.com.cn/s/blog_52215ca80102uwbt.html. Retrieved on 15 Nov 2015.

Pu’er City Xingying Corporation. Pu’er city Xingying Corporation Offers Assistance to Myanmar’s Panhkham Region Road Construction.Retrieved from http://blog.sina.com.cn/s/blog_5fa28d2a0101pczq.html. Retrieved on 15 Nov 2015. Source written in Chinese.

Radio Free Asia. 21 October 2015. Myanmar Military Clashes with Rebels in Shan State. Retrieved from http://www.rfa.org/english/news/myanmar/clashes-10212015163241.html. Retrieved on 07 Dec 2015.

Restoration Council of the Shan States. 8 October 2015. Statement on the Current Peace Process and Restoration Council of Shan State’s Position. Retrieved from http://www.mmpeacemonitor.org/images/2015/oct/rcss-released-position-statement-on-nca-eng.pdf. Retrieved on 08 Dec 2015.

Shan Herald Agency for News.20 May 2015.The Panghsang Summit: ExerceptsFrom a Journal. Retrieved from http://english.panglong.org/the-panghsang-summit-excepts-from-a-journal/. Retrieved on 21 Nov 2015.

Shan Herald Agency for News. 19 April 2012. Wa Leader: UWSA able to Defend itself. Retrieved from http://english.panglong.org/wa-leader-uwsa-able-to-defend-itself/. Retrieved on 07 Dec 2015.

Shan Herald Agency for News. 21 August 2015. Chiangmai to hold seminar on opening new border checkpoints. Retrieved from http://english.panglong.org/chiangmai-to-hold-seminar-on-opening-new-border-checkpoints/. Retrieved on 08 Dec 2015.

The Irrawady.July 2006.On Patrol with the Shan State Army. Retrieved from http://www2.irrawaddy.org/article.php?art_id=5947&page=1. Retrieved on 22 Nov 2015.

The Irrawady. 30 April 2015. Mongla Rebels say ‘Full Control’ of Region Brings Development.http://www.irrawaddy.org/multimedia-burma/mongla-rebels-say-full-control-of-region-brings-development.html. Retrieved on 07 Dec 2015.

Treerat, Nuolnai; Wannathepsakul, Noppanun and Lewis, Daniel Ray. February 2000. Global Study on Illegal Drugs: The Case of Bangkok, Thailand. Retrieved on 21 Nov 2015.

Weng, Lawi. 5 November 2015. Wa Leader Suggests Chinese Mediation Could Help Halt Conflict in Northern Burma.Yangon: The Irrawaday. Retrieved on 8 Nov 2015. Source written in Chinese.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 8 December 2014. Southeast Asia Opium Survey 2014. Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Report on Illicit Crop Monitoring. Retrieved on 10 Dec 2015.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 13 April 2013. Chapter 6: Trafficking of methamphetamines from Myanmar. Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Report on Transnational Organised Crime in East-Asia and the Pacific. Retrieved on 15 Nov 2015.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. March 2009. RASC25 – Drug control and development in the Wa Region of the Shan State, Myanmar. Retrieved from http://www.unodc.org/southeastasiaandpacific/en/Projects/1998_01/drug_control.html. Retrieved on 15 Nov 2015.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2015. Trends and Patterns of Amphetamine-type Stimulants and New Psychoactive Substances. Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/documents/southeastasiaandpacific/Publications/2015/drugs/ATS_2015_Report_web.pdf

Zhang, Sheldon and Chin, Ko-lin. 2014. A People’s War: China’s Struggle to Contain its Illicit Drug Problem. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution. Retrieved on 21 Nov 2015.

–

(Boh Ze Kai is a project intern with MISS. This Special Report is a part of Mantraya’s “Borderlands” and “Mapping Terror & Insurgents Networks” projects. All Mantraya publcations are peer-reviewed.)